Karachais are now 220 thousand people — compared to the peoples of the neighboring republic, they are half as many as Kabardins, but twice as many as Balkars. The Karachais are the closest kin to the latter (the common name is Taulals, i.e. highlanders), they speak essentially the same language, and Karachay-Balkaria did not become a region primarily for logistical reasons.

The ancestors of the Taulals were refugees from Alania who took refuge in inaccessible gorges. They were Iranian-speaking Ossetians and Turkic-speaking Polovtsians, who in times of peace guarded the steppe border. Until the 18th century the hermits of the mountains were bilingual, and in neighboring houses they prayed to Christ, Allah or Teiri — the Eternal Blue Sky. As a result, Alanian speech and Christianity prevailed in the gorges of Ossetia, closer to Georgia, and Turkic speech and Islam — in the gorges of Balkaria, where Beshtauel — a union of Five Mountain Societies, not yet states, but no longer tribes — emerged.

They were headed by taubii (princes) and tere (council and court), supported by uzdens (military nobility), and mostly inhabited by karakish (peasants) and slaves. Society was divided into tukums (clans, of which the Karachais had 32), yuyur (large families with common property) and eljamagats — rural communities with lands, including dzhaylyk (summer pastures in the mountains with shelters in caves), kyshlyk (winter pastures with log stalls «kosh») and small fields with millet, barley, wheat or corn on flat plots.

Geography came into play again: the mountain societies of Cherek and Chegem had both passes and hollows, and therefore for their neighbors they became something like Switzerland — a peaceful and rich neutral corner in the mountains. Khulam and Bezenghi lived behind their narrows in deadlock, feuding and searching for a way out. Baksan, on the other hand, for lack of a gully, was a passing yard, and in the 15th-17th centuries its inhabitants, the most bellicose of the Taulala, under the legendary Kyarchi and the authentic prince Bekmurza Krymshamkhalov (most likely, both are real, but in different times) migrated to the Kuban.

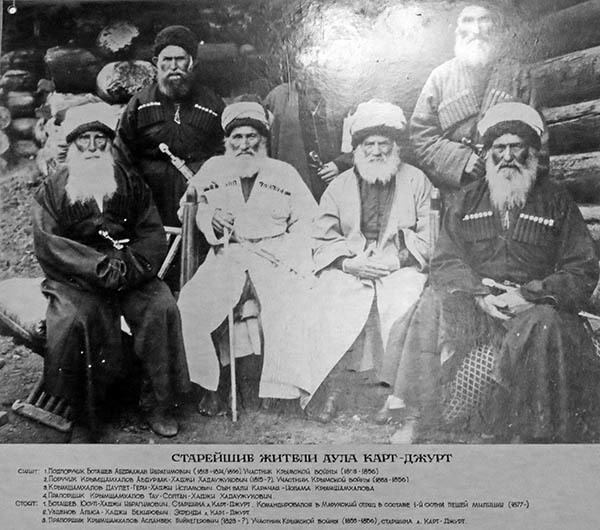

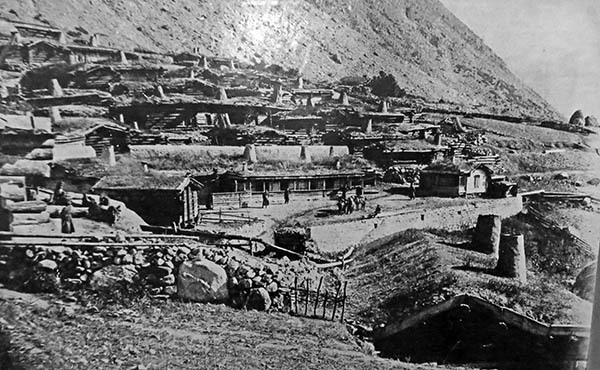

According to the legend, the mountaineers were looking for the ancestral homeland, which the prince had to identify by the smell of Black Grass — karachai. More likely, the exodus took more than one century, and judging by the notes of the first Russian ambassadors Fedot Yelchin and Pavel Zakhariev, who in 1639 were received by Bekmurza’s son Elbudzuk, then the highlanders lived along both rivers. By 1828, when George Emmanuel defeated the mountaineers in the Battle of Khasauki and Karachay became a part of Russia, the whole nation was contained in three villages — Khurzuk, Uchkulan and Kart-Dzhurt in the very upper reaches of the Kuban.

With the laying of the wheel road (1855), the end of the Caucasian War (1864) and the abolition of serfdom and slavery (1867) the mountaineers began to settle down the river, on the lands abandoned by Abazins and Circassians. By the end of the century the Karachais had separated from the Balkars and significantly outnumbered them, but the same Taubians Krymshamkhalovs were at the head of the people. For example, Islam Krymshamkhalov — poet, artist, educator and founder of the resort in Teberda.

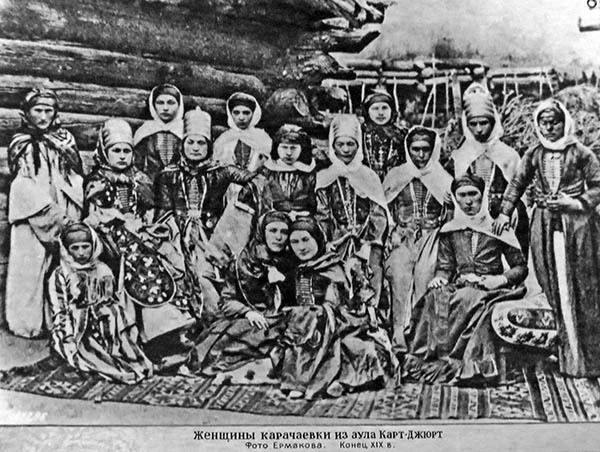

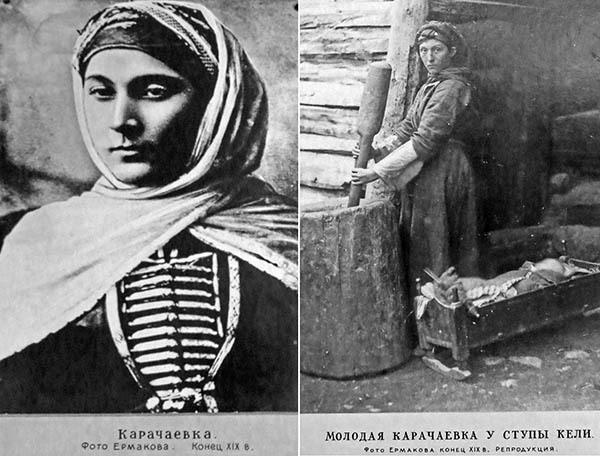

The Karachai language sounds similar to Kazakh, and one can hear it not only from passers-by, but also on the radio. Outwardly, despite the «black» name, Karachais are the brightest of the local peoples — down to their russet hair, blue eyes and the appearance of a man from near Kaluga.

Like all Turks, Karachais are not fanatical in Islam, but at the same time one of the most terrible forces of the Chechen wars was the Karachai Jamaat, which was founded under the supervision of Khattab by businessman Achimez Gochiyayev and Yusuf Krymshamkhalov, a descendant of princes: their 1999-2004 bombings of high-rise buildings and subways killed half a thousand people. In personal communication Karachais are remembered to me as a people sharp, glib, self-confident: Karachai is a Balkar micro-America.

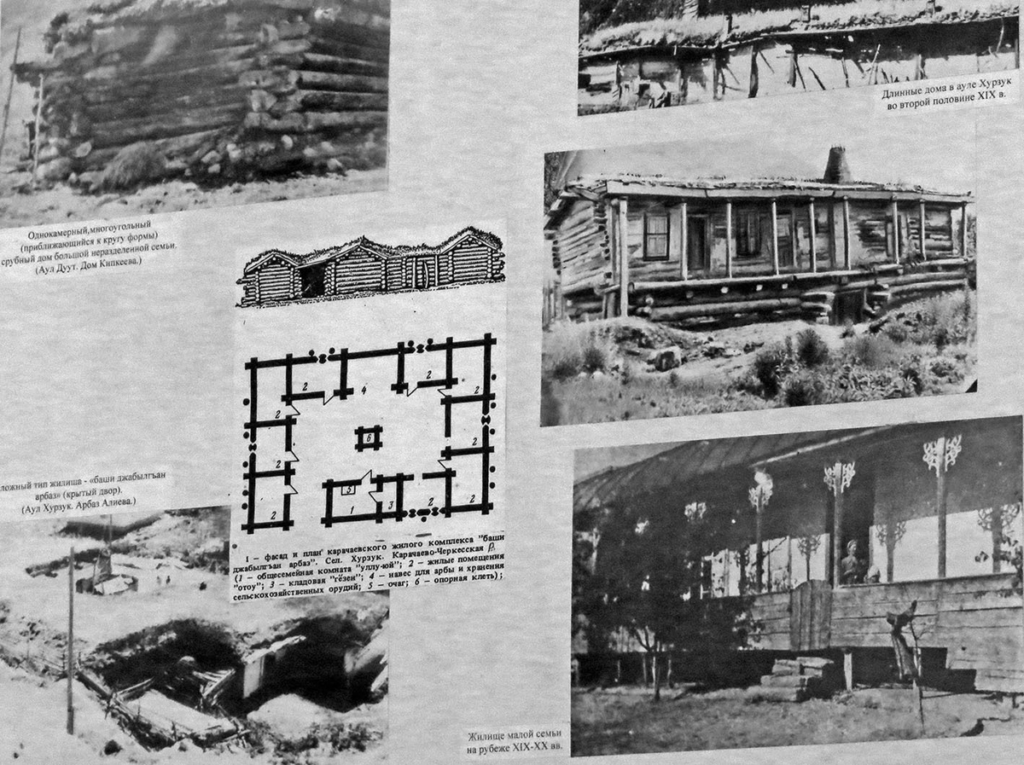

On mountain pastures Karachais have succeeded in breeding: Karachai horse is famous for its endurance in conditions of thin air and powerful hooves, and Karachai «black lamb» — for its healthy meat. Kabaks (as auls were called here in pre-Russian times) of taulals consisted of saklins with flat sod roofs and powerful chimneys, and in Karachais they were all wooden:

The main types are single-chamber houses, long houses with separate entrances of rooms and arbazi — dwelling carriages:

Abandoned and turned into stable, they are still found in old auls. In the courtyard of the layout reminds of the Turkic past stele-konovyaz, a distant relative of the sarga of Altai or Yakutia.

In Karachay life typical mountain items differed only by their names: here on the left are men’s papakhas (chirpa burk) and women’s caps (okya burk), belts (belibau and kyamyar respectively), shirts (kyolek), cherkeskas (erkeshi chepken) with daggers (kama), women’s dresses (chepken) with bibs (tuyme) and shawls (chille). But next to them is a voloichnaya hat, and above it is a felted carpet ala-kiyiz, familiar to me from Kyrgyzstan or the nomads of Mongolian Kazakhs. Karachay cuisine has shurpa and lagman, which taste and look quite different from the same dishes of Crimean Tatars or Uzbeks.

There are also khychin, but not like the Balkars, just flatbreads with stuffing. The main contribution of Karachay to the world culture was gypy (kefir), the fungus of which was a local endemic, and the story of its acquisition by dairyman Ivan Blandov from prince Bekmyrza Bayochorov, who kidnapped his employee, would make a novel. Looking closely at the Karachais, it is not so difficult to recognize in them the surviving Polovtsians…. However, the yurt from the frame above is not theirs after all: there is another Turkic people, the Nogais, in the KCR.