The rule of the Mamluks in Egypt can be assessed in different ways — from bright to the darkest colors. However, one thing remains undoubted — the Mamluks gave a new impetus to the development of Muslim civilization, which by that time was on the verge of disaster.

The predecessors of the Mamluks can be considered to be gulams — young and brave warriors, to a greater extent mercenaries rather than slaves, who constituted the guard in the Abbasid Caliphate. Once in the Muslim army, mercenaries were able to reach the highest levels of command, and as a result were often appointed governors of provinces.

One such governor was Ahmad ibn Tulun, who ruled Egypt from 868. Gradually, the power of the army commanders became greater and greater, which translated into the granting of high authority.

Thus, for example, already in 937 the governor of Egypt was given the right to bear the title of Ikhshid, which actually symbolized independence. Shortly before the death of the successor of the first Ikhshid, Egypt was taken over by a viceroy close to the court. By the time the Fatimids arrived, the real ruler of the country was the grandson of the founder of the dynasty.

It should be noted that in the eastern part of the Caliphate gulams were mainly representatives of Turkic tribes. Some of them were able to establish their own states with their own dynasties, one of which, for example, was the state of Ghaznavids, whose rulers still showed nominal subordination to the Abbasids.

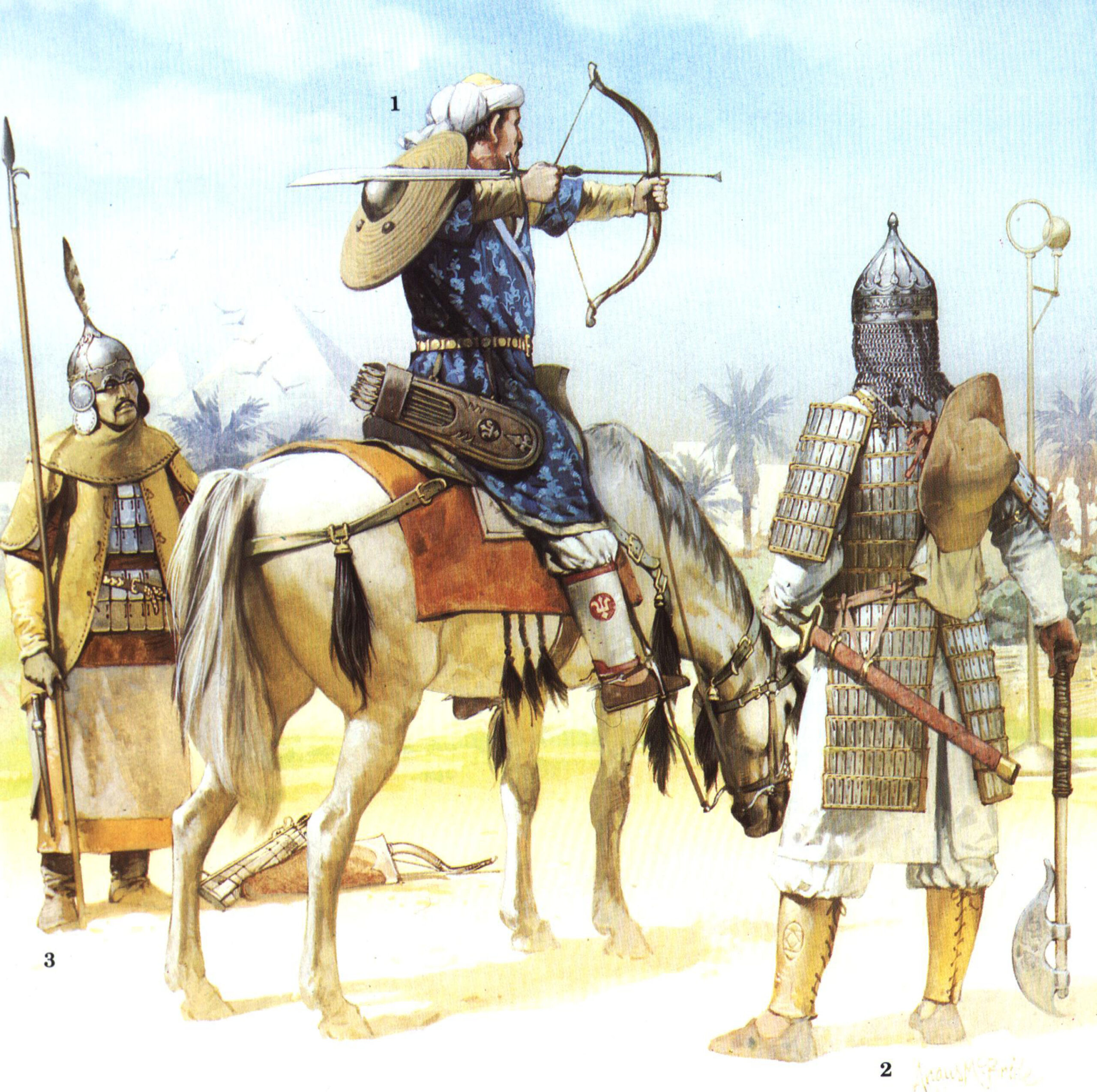

As for Egypt, mercenaries there represented two forces — natives of the East and representatives of Africa. Africans to a greater extent were Nubians — black inhabitants of Sudan. Orientals were not only Turks, but also Caucasians, who were usually called Circassians, although among them there were representatives of different peoples of the Caucasus. Among mercenaries there were also Slavs.

When the Ayyubids came to power in Egypt, they relied on mercenaries, who were called Mamluks. And in eighty years mercenaries already come to authority and found their own dynasties.

One of the outstanding rulers of the Bahrit dynasty, who were in power for more than a century and were representatives of the Turks, was Sultan Beibars (ethnic Kazakh). It was under his command in 1260 that the attack of the Mongolian pagan Khan Hulagu, who had previously traveled with fire and sword through the lands of the Abbasid Caliphate, finally destroying it, was stopped.

It should be noted that one of the reasons for the attack of Mongolian troops on the Caliphate was a disgusting act of one of the autonomous rulers of Khorezm (Khorezmshah), who destroyed Mongolian ambassadors sent to him with a trade mission. After such humiliation, the angry Mongol troops destroyed everything on their way, trying to get to the humiliated Khorezm Shah, who fled from the capital of his autonomous state, taking refuge on one of the islands of the Caspian Sea.

Having conquered practically all Abbasid territories, except for the southern provinces, the Mongol armies reached Syria and Palestine, touching Egyptian possessions. It was here that the famous battle of Ain Jalut took place, where the troops of Hulagu Khan suffered a significant defeat.

Realizing that the Egyptians could hardly cope with the powerful Mongolian army, which could quickly replenish its ranks at the expense of the conquered peoples, Sultan Beibars made a great diplomatic move, asking for help to Khan Berke — Hulagu’s uncle. The thing is that by that time Golden Horde Khan Berke had already accepted Islam, and wise Sultan Beibars knew about it.

In one of his letters, the Sultan urges to «destroy the common enemy» and emphasizes that he «will support him in this». In response, Khan Berke writes: «Let the Sultan know that I fought with Hulagu, with whom we are of the same blood and flesh, for the elevation of the Great Word of God, let him know of my boundless love for Islam. I fought Hulagu because he is doing injustice, and those who do so are infidels to Allah and His Prophet ()…».

He also asks Beibars to send armed forces to the Euphrates crossings to cut off any avenues for Hulagu. To this, Sultan Beibars orders that «a large number of soldiers be sent from all parts of Egypt …». As can be seen from the correspondence, an alliance was concluded between the two powers.

But not only with the Mongols had to fight the Mamluk rulers, because since the time of the Fatimids in the lands of Palestine remained troops of crusaders, which were partially expelled from Palestine great Salahuddin. Clashes with the Crusaders continued after his death, as new campaigns were organized in Palestine.

One of them, the seventh, undertaken by the French king Louis «the Holy», ended in total and unconditional defeat. His army was defeated, and he himself and his inner circle were captured and released for a large ransom. The Mamluk army played a decisive role in this victory.

But the crusaders did not rest on this, and organized another, this time the last campaign, which also ended in complete failure. King Louis «Saint» apparently could not come to terms with his past failure, but never realized that his cause is not holy.

As a result, having suffered several sensitive defeats, the crusader troops lost almost all their fortresses, and the king himself died of the «black death», as the plague was called in his time. In 1291 the Crusaders were completely expelled from the Holy Land and did not appear there again.

In 1390 the power in Egypt was in the hands of another branch of the Mamluks, whose representatives were mainly natives of the Caucasus. These people were called Circassians — they also had to repel attacks and make alliances. Tamerlane became a common enemy for the Golden Horde khans and Mamluks. However, this time there were no big clashes between him and the Mamluks, as Tamerlane preferred to smash his rivals one by one.

The first of them was the Horde Khan Tokhtamysh, the second ruler of the Ottomans Bayazid. And although both states were defeated by Tamerlane, nevertheless, he never dared to attack the possessions of the Mamluks.

The end of the independent rule of the Mamluks was put by the Ottomans, as a result of whose successful actions Egypt became part of the Ottoman Caliphate. But even after that the Mamluks retained their influence for several more centuries.

The state of Mamluks in the eyes of modern readers appears as a kind of Spartan regime, where «the ball rules» exclusively military craft, without any achievements in other spheres. Meanwhile, according to historical data, in addition to military achievements, there were also cultural ones.

One such achievement is the creation of the first Arab-Kipchak dictionary. There were other dictionaries created in Egypt, one of which was devoted to four languages at once: Arabic, Persian, Turkic and Mongolian.

During the reign of the Mamluk sultans, many works of fiction and literature were also created, of which, unfortunately, only a few copies have survived. For example, the poem «Khosrow and Shirin» written in the Kipchak language, the only copy of which is kept in the Paris National Library. Its author is a native of Desht-i Kipchak.

In 1391, Saif Sarani, a Kipchak from the South Russian steppes, completed his famous work «Gulistan Bit-Turki», which is dedicated to the Egyptian amir of Turkic origin Tayhas.

The Turkic translation of the masterpiece of world literature «Shahnameh» (the beginning of the 16th century) in photocopy and transcription was published in Warsaw in 1965. This Cuman translation was made by Tatar Ali Efendi, who worked on the translation for 10 years. The book was published on the advice of the last Mamluk sultan.

But the most significant work written in the Cumans language in Egypt is the poem «Iskandername». It describes the events of the XIV century: the flight of Sultan Ahmed from Baghdad, Timur’s campaign in Turkey, the death of Bayazid Lightning, the death of the Golden Horde Khan Tokhtamysh and others.

It should be noted that the majority of poets and writers of that time in this region were natives of the South Russian steppes, and on this foundation in Egypt and Syria the Cumans culture developed. But this was due not so much to the fact that the Mamluks ruled in Egypt, as to close diplomatic, political and cultural ties with the distant homeland, where the Golden Horde was located at that time.

Many representatives of the Turkic literature of the Golden Horde period moved to Egypt for one reason or another and continued their creative and social activities there. Such, for example, were Mahmud Ibn Fatshah Sarai (1374), Ruki al-Din al-Krimi (1377), Saif Sarani (139b), Ibn Muhammad al-Krimi (1377. ), Shihabeddin Sarash (known as Maulana Zadeh Al-Ajami 1398), Mahmud Sarai Gulistani (1398), Mahmud Sarai Al-Kahiri (1399), Berkeh Faqih, and many others.

Ibn KhaldunThe two greatest historians of the time, al-Maqrizi and Ibn Khaldun, whose works influenced European minds as well, lived and worked in Egypt during the reign of the Mamluks.

Thus, in a comparative analysis, it becomes obvious that the famous Machiavelli used the works of Ibn Khaldun. It is also known that under the Bahrits Egypt was famous for its doctors — ophthalmologists (who even then treated cataracts), surgeons, gynecologists and even veterinarians.

Thus, Turkic Mamluks in Egypt distinguished themselves not only on the battlefields as skillful warriors and commanders, but also made a huge contribution to the development of world literature, poetry, medicine, as well as architecture. An example of architecture is, in particular, one of the most beautiful Egyptian mosques in Fustat, which was built by the governor of Egypt Ahmad ibn Tulun in 879. In Cairo there are also preserved magnificent monuments of Mamluk architecture, giving an idea of medieval Cairo, including several dozens of mosques.

Although there were cruel rulers among the Mamluks, which is unfortunately difficult to avoid in a hereditary form of government, historians generally note the rise of economic prosperity and the flourishing of culture and art in Egypt during the Mamluks’ time.

Yes, the cultural environment really influences inhabitants, and Islamic civilization, as it is known, had and still has the greatest potential for development of peoples, as exemplified by the former mercenaries, thanks to whom Muslims not only stopped the Mongol invasion and expelled the Crusaders, but also revived the former greatness of the Caliphate in various fields, including culture and science.