The word “khashar” is translated from Arabic as “joint free labor. And in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, since Soviet times, it has been used in the sense of “subbotnik”. That is, people, not for money and relatively voluntarily unite for the sake of some cause, which will go for the common good.

But eight hundred years ago, things were much more severe. The term was applied to the Mongols’ most fearsome but effective tactic, which allowed them to take enemy cities without too many casualties. Nomads drove the local rural population under the besieged fortress, which they used for siege work. And sometimes they even went on the attack, so that enemy arrows, darts, stones, burning tar and boiling water fell into the expendable material, but not in the successful steppe cavalrymen.

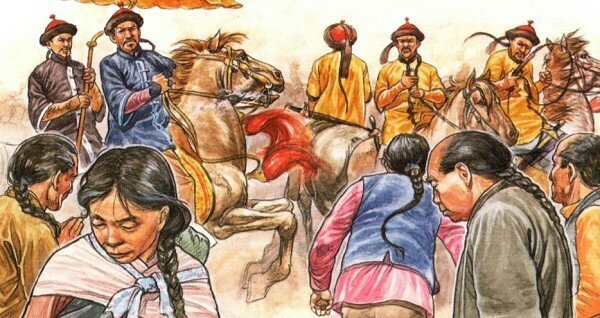

Modern people are drawn some unpleasant pictures when thousands of old men, women and children are climbing the walls of the city, being driven by Mongolian warriors with spears in the back. The besieged, out of pity for their loved ones, either do not dare to open fire at all, or miss the attack of the Mongolian detachment, which behind a human shield hides from the enemy.

But was the khashar as terrible as it is portrayed?

As has already been said, the word itself is Arabic. But it began to be used in Muslim Persia in the Middle Ages as a designation of some kind of public works. And in general, for centuries the local population gathered in large labor groups to dig irrigation canals, build public buildings, erect fortifications and other socially important activities.

The Mongols borrowed this concept during their conquest of Central Asia. But the very tactics of using free labor force were actively used since the conquest of the Jin empire of the Jurchens in Northern China. By that time it was disintegrating naturally, the Chinese did not want to live under the rule of harsh and greedy foreigners. As it always happened to them, the inhabitants of the Celestial Empire in droves ran over to the side of the new conquerors, who promised at least some, but changes.

Apparently, at that time the kolkhoz khashar was a relatively voluntary affair — the Chinese were helping their allies to defeat their common enemies and their oppressors. Therefore, of their own free will, they performed a great deal of auxiliary work that accompanies any siege.

That is, they set up fences, dug ditches — or, on the contrary, buried them, carried stones for throwing guns, cut wood, and, if necessary, built canals to change the courses of rivers. It is likely that many went into battle — out of rage against their enemies or to plunder.

However, things were different in Central Asia and Iran. The Khwarizmians and Seljuks were not the worst rulers. Again, they converted to Islam long ago, lived in these countries for several hundred years, and did not oppress the common people too much. At least, they did it within the usual medieval level of atrocity.

Therefore, the Mongols found no allies among the locals here. And they began to recruit people to the khashar in a voluntary-coercive way. In other words, those who refused were chopped off their heads. Here is how Persian Shihab-ad-din Muhammad An-Nasawi, personal secretary and biographer of Khorezmshah Jalal ad-Din, who compiled his biography, wrote about it.

At the storming of Nisa, the ancient capital of Parthia “…twenty catapults were set up, which were dragged by men gathered from the regions of Khorasan. The Tartars drove the captives under cover-houses like battering rams, made of wood and covered with skins. If the captives returned without bringing the cover to the wall, their heads were chopped off. So they were persistent and finally made a breach that could not be bridged…”

When Jalal al-Din was forced to retreat westward, Jebe, Subudai, and Tohuchar were sent in pursuit. “And whenever one of these detachments of a thousand horsemen attacked an area, he would gather men from the surrounding villages and move with them to the city, where their forces would set up catapults and punch gaps in the walls until they captured the city.”

Twenty years after the conquest of Northern China and Central Asia, a mission of the Roman Pope went to the capital of the Mongol Empire, and the Franciscan friars made a detailed report on their trip in 1245. As a result, a work was published in Latin called “The History of Tartars”. Among other things, it contained the following passage:

The Mongols used the local population to fill in the moats of besieged cities. The Southern Sun diplomat Zhao Hong wrote in 1221: “Whenever they attacked large cities, [they] first attacked small towns, captured [the] population, hijacked [them] and used them for [siege work]… [The Tartars] chase [them] day and night; if [the people] lag behind, they are killed.

Thus, none of the contemporaries of the Mongol conquests mention that khashar were used directly for storming cities — only for the purpose of performing preparatory work, which the Mongols themselves were squeamish about. They were treated exceptionally harshly, probably were fed at starvation, and their lives were not spared.

But none of the medieval authors, including Russian, specifies that children and women were used for this purpose. Where physical strength was required, they were of little use. So, colorful pictures of crying slave girls and little children climbing the walls should be considered modern fiction.