The Bukhara Khanate is one of the three Uzbek states in Central Asia that existed from the 1500s to the 1920s, but for the last half century under Russian protectorate. It was a powerful Muslim power that played a significant role in the history of the entire region and each of the peoples who lived there. At one time or another, its power extended over all or part of the territory of such modern countries as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Afghanistan.

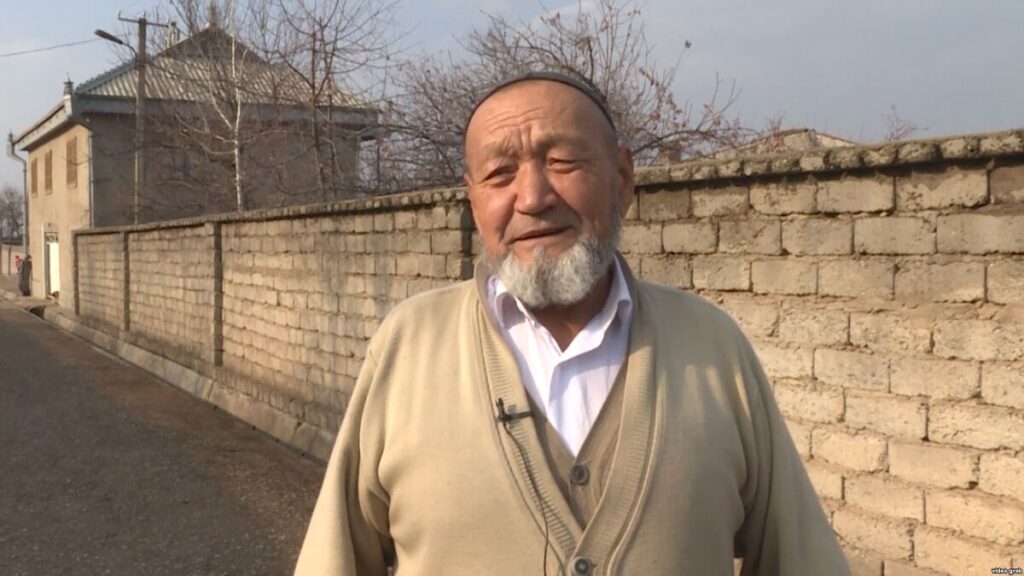

Muhammad Sheibani

Let us tell her story.

Tamerlane’s inept heirs were unable to contain the disintegration of the empire after his demise. Vast Iranian and Caucasian possessions fell away within a couple of decades, and Central Asia was divided into principalities ruled by numerous descendants of the great conqueror. They were lucky that for a long time there was no force that could give them a final blow of mercy.

But at the end of the 15th century, such a force appeared. Mohammed Sheibani, one of the influential Chingizid rulers of the eastern part of the former Golden Horde, was defeated in the battle for power in his native steppes. In his youth he had been trained in Islamic sciences in the Timurids’ domains, and therefore well understood their political and military weakness.

This man managed to rally around himself all his numerous kin and even brought allies from the Astrakhan Khanate. With these forces in 1500 Maverannahr was captured, and then conquered the historical region of Great Khorasan, now divided between Afghanistan and Iran. Even its demise due to tactical errors from Iranian troops did not result in a significant loss of territory.

That state, which took shape in Central Asia in the 1510-1520s, became known as the Uzbek Khanate — after the nomadic Uzbeks of the Golden Horde, who acquired the name in honor of its ruler, Uzbek Khan. After the khan’s residence soon left the Timurid capital of Samarkand and moved to Bukhara, this power was increasingly referred to as the Bukhara Khanate.

Territory in the 16th century

The 16th century can rightly be considered the period of Uzbek great power. The Sheibanids ceded the steppe to their close relatives, the Kazakh khans, but controlled most of the settled territories of Central Asia. The basis of their state was Maverannahr, i.e., the historical area between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. The Timurids, the former owners of this land, were forced to leave for India, where they founded the Mughal dynasty.

The Ubeks were now subject to the Pamir foothills, which became the basis for the present Tajikistan, the southern part of Kyrgyzstan, the northern part of Afghanistan inhabited by Tajiks, and their authority was recognized by many Turkmen tribes. Their supreme power was also recognized by Khorezm, ruled by Uzbek khans from a related but rival dynasty. And for several decades, this ancient state was directly included in the Bukhara possessions.

Many rulers of the «Golden Age» were highly educated people. They built mosques, madrassas, caravanserais, finally completed the architectural ensemble Registan in Samarkand, which was started by the great Timur. For the first time since very ancient times they were engaged in the arrangement of irrigation systems. There were among them delicate connoisseurs of oriental poetry, and some of them even wrote poems themselves. The Tajik dialect of Persian remained the court and administrative language under them, although Uzbek gradually grew in importance over time.

In the century after the conquest, many nomadic Uzbeks of Kipchak origin from the Kazakh steppes settled in towns and villages among their subjects, who spoke the Karluk dialects of the former Chagatai Khanate. But for a very long time the military strength of the Khanate was still based on contingents of nomads who fought in accordance with Horde traditions. The descendants of these soldiers are the present-day Lakai Uzbeks.

During the 16th century, the Bukharans conducted many offensives to gain full possession of Khorasan. However, despite a number of successes, they failed to win a complete victory. The reason was that the Uzbek aristocracy did not want to strengthen the power of their khan, and they were satisfied with plundering rather than conquering these lands. The second problem was that because of their isolation and strong steppe traditions, the Uzbeks did not have artillery in their army, and their infantry with firearms appeared in small numbers and much later.

The Uzbeks managed to stop the Iranian offensive and keep Central Asia in the fold of Sunnism. The peak of their military success occurred in 1602, when the great battle of Balkh took place. With the help of 80 thousand cavalrymen, Baki Muhammad Khan managed to stop 120 thousand Persian army, which included 10 thousand riflemen with multuks and 300 cannons (according to other data, the Uzbek and Iranian armies numbered 20 thousand and 50 thousand people respectively). Thus, the Bukhara Khanate managed to surpass the superior military leader of the Iranian Shah Abbas the Great, who single-handedly crushed the Ottoman Empire and mocked Europeans who were incapable of standing up to the Turks.

But eventually, this state ran into trouble. Several successive plague epidemics, a series of heavy Persian military campaigns, the long reign of Abdullah II, who, though he proved to be a great builder, was an orthodox Muslim, after which the country began to stagnate intellectually — all these combined to weaken the Bukhara Khanate. Khorezm (i.e. the Khanate of Khiva) managed to assert its independence, the Iranians in alliance with it took away a large part of Khorasan, and the long-standing and principled opponents, the Kazakhs, took advantage of this and attacked the northern Bukhara cities.

After the finalization of the Uzbek states. In yellow is the «tribal zone»

Therefore, in the 17th century, the Uzbek power lost half of its territories, and despite further economic recovery, the opportunities of its rulers were diminished. Two of the most important geopolitical problems were the Europeans’ opening of alternative routes to India and China — the khanate was deprived of revenues from transit trade. And when the Iranians did recapture the Afghan city of Balkh, the Uzbeks were deprived of communication with India.

From then on, they were culturally and economically isolated. To the west, south and east, they were surrounded by the Mughals and Iranian Shiite dynasties, longtime opponents of Uzbek power. To the north were the Kazakhs, who could not miss an opportunity to attack the Syr Darya cities. In 1709, taking advantage of a popular uprising in Fergana, one of the local influential Chingizids proclaimed the creation of the Khanate of Kokand, which resulted in the loss of the east. Over time, the Dzungarian power grew in strength, which did not seem to threaten Bukhara directly, but its pressure led to more frequent invasions of the Uzbek state by the Kazakhs.

Taking advantage of the long period of turmoil, Bukhara was conquered in 1740 by the great Azeri ruler of Iran, Nadir Shah. Leaders of the influential Uzbek family of Mangyts under him became viceroys and military commanders, and after the passing of the Iranian Shah, they sent the legitimate khan to heaven and received the throne. The people welcomed them — in the eyes of the nobility and the ordinary population, yesterday’s khan’s viziers turned out to be the only force that could protect Sunnism in Central Asia and unite the country. However, after the removal of the Chingizids, the Uzbek state could no longer call itself a khanate. From that time it was called Bukhara Emirate.

Thus, due to the gradual weakening of Bukhara, three Uzbek states, or rather three countries with Uzbek dynasties, appeared in Central Asia. The Khanate of Khiva was the most Turkic of them all, although it was not homogeneous in ethnic composition — along with sedentary Khorezmians, its subjects included Turkmen tribes. Kokand, despite its strong Uzbek core, was half Tajik and extended its power to the southern Kyrgyz tribes.

Bukhara was from the middle half: Uzbeks numerically dominated the country, but Tajiks were in the majority in the capital Samarkand and Bukhara, and the Syr Darya towns had a mixed Uzbek-Kazakh population due to years of struggle with the Kazakh khans. Thus, Bukhara Emirate from a regional power slipped to the honorable, but really meaningless title of the first among equals. Moreover, due to the lack of artillery and a small number of hand firearms, its army was no longer a threat to anyone.

In 1868 Bukhara Emirate was conquered by Russia, lost part of its territories and recognized its protectorate. However, this led to some stability: St. Petersburg helped to return some of the possessions ceded to Kokand, protected it from the Persians, and popular uprisings were now suppressed with the participation of Russian troops, while in the internal affairs of the Uzbeks did not interfere much, only eliminated slavery.

In the Russian Empire, the emirs and their entourage enjoyed numerous privileges, received high ranks in the army and maintained active relations with the Volga-Ural and Caucasian Muslims. The funds of the last emir Seyid Alim-khan were used to build a cathedral mosque in St. Petersburg, quite similar to the best examples of Samarkand.

But popular movements after 1917 led to the revolution in Bukhara and the subsequent invasion of the Reds. The emirate was liquidated and later formed the main part of the Uzbek SSR.