The history of the Central Asian region in the XIII-XVIII centuries is directly connected with the emergence and development of the Mongol Empire, which finally took shape by 1260.

In medieval historiography, this state is known as Yeke Mongol Ulus (Great Mongolian State). In its basis Genghis Khan, the founder of the empire, put the principle of military organization, historically inherent in the communal-territorial structure of most Mongolian tribes.

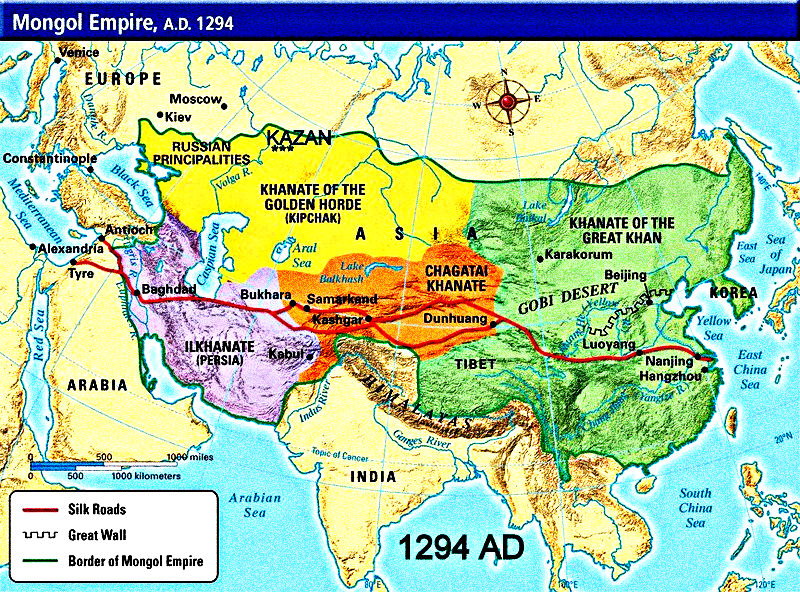

The empire of Genghis Khan and his successors stretched from China (Yuan) in the east to the Danube and Carpathian Mountains in the west. The southern borders of the empire covered modern Iran, Iraq, and the eastern part of Syria (the state of the Ilkhans).

By the end of the 60s of the XIII century the Mongol Empire began to disintegrate into 4 ulus — states, each of which was headed by khans — descendants of the founder of the empire. These independent and feuding with each other states were:

1. Golden Horde, which included the entire Great Steppe (Desht-i Kipchak) from the Irtysh — in the east to the Danube — in the west and all Russian principalities. This state was ruled by the descendants of Dzhuchi (d. 1227), the eldest son of Genghis Khan.

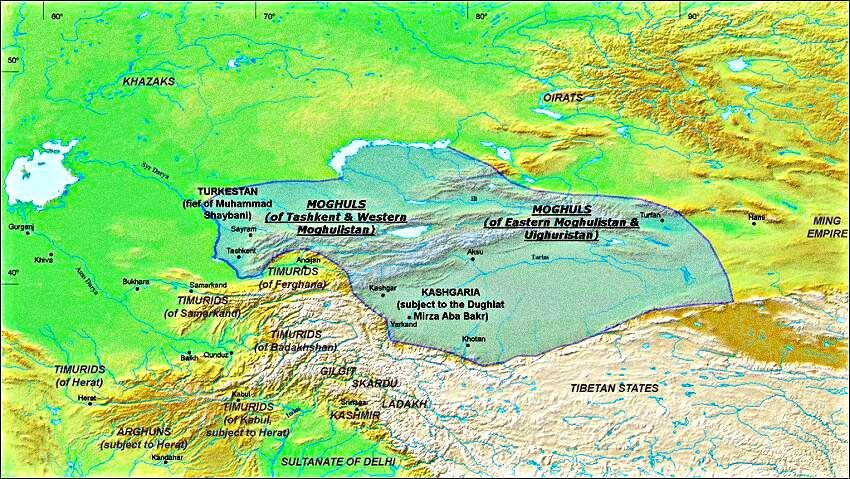

2. The Chagatai state, which included Maverannahr (between the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers), Semirechye (modern Kyrgyzstan and part of southeastern Kazakhstan), Kashgaria (the southern part of Xinjiang province in China) and was named after Genghis Khan’s second son Chagatai (d. 1242).

3. The Khulaguid state, created in Iran by Khulagu Khan (d. 1265), son of Tului, Genghis Khan’s fourth son. Hulagu and his successors bore the title of ilkhan, so in the research literature the Mongol rulers of Iran are called ilkhan («lord of the tribe»).

4. The state in Mongolia and China with the center in Karakorum (the great khan’s headquarters) and then in Khanbalik (modern Beijing), which was ruled by another branch of the descendants of Tului (d. 1233), namely the descendant of the great khan Khubilai (d. 1294), brother of Hulagu. The official name of this state was the Yuan Empire.

Historically, the fate of these 4 Mongol states developed differently. Tului’s descendants in the Yuan Empire were Chineseized and ruled until 1368, when they fell under the blow of the national liberation movement of the Han Chinese under the leadership of Zhu Yuan-zhang. In Mongolia itself, the Chinggisids of this lineage ruled until the 17th century. The state of Hulagids in Iran finally has broken up in the beginning 50th years. XIV century. The Chagataid dynasty ceased to exist at the end of the XVII century. The Dzhuchids, descendants of the eldest son of Genghis Khan, retained supreme power in Desht-i-Kipchak and adjacent regions until the middle of the XIX century.

Of the mentioned 4 Mongolian states, the Golden Horde (ulus Dzhuchi, Ulug ulus) and the Chagataid state (Mogolistan) are of special importance for the political and ethnic history of Central Asia.

The state of Chagataids (Mogolistan)

Possessions of the second son of Genghis Khan, Chagatai, included East Turkestan (Kashgar), Maverannahr, the most part of Semirechye, and also the lands of the left bank of Amu Darya Badakhshan, Balkh, Ghazni, Kabul and territory in the south up to the river Sindh. The Horde (Chagatai’s headquarters) was originally located in the Kuldzha region on the southern coast of the Ili River.

The date of birth of Chagatai is not precisely established, but it is known that even during his father’s lifetime Chagatai was considered an expert in state law and the highest authority in matters related to Mongolian laws and customs. Chagatai took part in many military expeditions of his father, including campaigns to China, against the empire of Khorezmshahs, etc. However, after the death of his father in 1227, Chagatai was always in his ulus and did not participate in military actions.

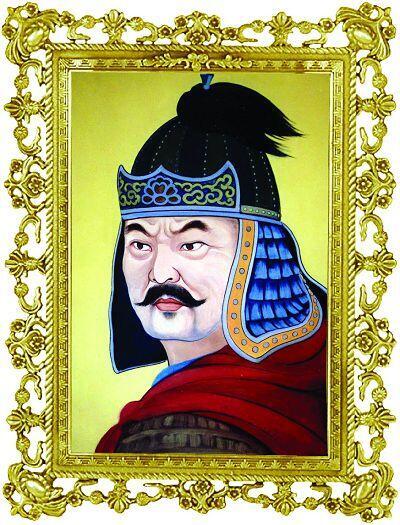

Chagatai (Mong. Sagaadai-khan (c. 1183-1241 or 1242) was the second son of Genghis Khan and is considered the founder of the Chagatai state. He ruled Central Asia until the end of his life. According to his father’s will, he controlled the governments of all ulus.

Chagatai’s endeavors to improve his ulus are well known. By his order the road along mountain passes from East Turkestan to Iliysk valley was built, which included 48 bridges, 8 tunnels and other constructions. New settlements, auls, etc. were founded. Chagatai’s nomadic residences eventually turned into large administrative and trade centers (for example, the settlement of Kutlug in modern southern Kazakhstan).

As the eldest in the khan family after the death of his father and elder brother Juchi (both died in 1227), Chagatai enjoyed unquestionable authority. In 1228-1229. Chagatai actually insisted on proclaiming Ugedei (1229-1241) as the great khan. As a result, Chagatai had such real power in the empire that the great khan did not make any important decisions without his advice and approval. If we take into account that Ugedei, especially in the last years of his reign, spent time in incessant revelry and drunkenness, the influence of Chagatai on state affairs was enormous.

As a ruler of Muslim regions, Chagatai absolutely ignored Islamic traditions and customs, which often contradicted the Mongol Yasa.

The bloody cruelty with which Chagatai punished all misdeeds made his name hated by Muslims. The largest Russian orientalist V. V. Bartold was the first to note that Chagatai was the only one whose name became, firstly, an official term for the Central Asian Mongol state, secondly, the name of the nomads who made up the equestrian force of the Chagatai state (Chagatai), and thirdly, the name of the Turkic literary language formed in Central Asia during the Timurid era.

After Chagatai’s death in 1242, he was left with eight sons. Even during his lifetime, Khara-Khulagu, the grandson of the deceased, was appointed his successor. However, after Ugedei’s death, the situation in the Mongol Empire became more complicated. The so-called «vague period of five-year interregnum» began, during which Ugedei’s widow Turakin remained as the ruler of the empire. At this time the political union of descendants of Tului and Djuchi against descendants of Ugedei and Chagatai was formalized.

Turakin-khatun

At the end of the confrontation in the 50th century, a «bi-umvirate» is actually established in the empire, with the Chinggisids of the Juchi and Tuluya clans at its head. Their opponents tsarevitch from the Chagatai and Ugedei clans were accused of conspiracy against the great khan Munke and then partly executed, partly exiled.

In the 60s of the XII century the unity of the Mongol Empire was dealt a final blow. In 1259 Munke dies and his sons Arig-Buga in Mongolia and Khubilai in China are proclaimed great khans at the same time. Ulus Chagatai becomes the arena of struggle between them. The victory in this struggle was won by Arig-Buga’s protégé, Chagatai’s grandson Alguy (1261-1266), who actually proclaimed the independence of the Chagatai ulus from the power of the great khan. In addition, Alguy managed to defeat the troops of his former patron Arig-Bug in several battles in Semirechye and from 1263 became an independent ruler. According to V.V. Bartold, Alguy can be considered «the founder of an independent Mongolian state in Central Asia» [2, p. 541]. [2, с. 541].

After Alguy’s death the power in Central Asia passed into the hands of Ugedei’s descendants and Haidu (1269-1301) became khan. During his reign the state of Central Asian Chinggisids, as an independent political unit, received its final form. At the hural, which took place in the spring of 1269 on the bank of the Talas River, Haidu proclaimed complete independence from the authority of the great khan. The boundaries of the Haidu state widened and narrowed depending on military successes and failures. In the victorious years, it included the territories of northern Afghanistan, southern Kazakhstan steppes and part of the Caspian Sea.

In 1301 Haidu died and Chagatai’s descendants came to power again, which sharply changed the internal political course of the power elite in the ulus.

As is known, among the Genghisids and the highest representatives of the military and administrative aristocracy, even in the years of Genghis Khan’s reign, two sharply opposite tendencies emerged: centrifugal-nomadic and centralist.

The first trend was represented by the Mongol and Turkic nomadic nobility, which firmly stood for the preservation of nomadic life and steppe traditions and was extremely hostile to sedentary life and cities.

Representatives of the second direction sought to create a strong centralized state with strong khan’s authority and thus curb the centrifugal aspirations of the military nomadic nobility.

The centralist direction was supported by a small group of nomadic aristocracy closely connected with the khan’s family, officials of the central state apparatus, as well as a part of Muslim authorities and the majority of merchants.

The most prominent promoter of the nomadic tendency was Genghis Khan himself, and of his descendants the great khan Guyuk and the ulus khan Chagatai. The great khans Ugedei, Munke and ulus khan Dzhuchi were the conductors of the second trend.

According to I. P. Petrushevsky, the essence of the dispute between the two directions concerned the question of the methods of exploitation of the indigenous population «and at the same time the question of merging with the feudal upper class of the conquered countries, the adoption of their statehood, ideology and cultural traditions» [14, p. 51]. [14, с. 51].

In Chagatai ulus longer than in other states formed by the Mongols in the conquered countries, the basic principles of centrifugal-nomadic tendency remained in force.

At the Talas khural in 1269, the khans and noyons (emirs) committed themselves to live not in cities but in the steppe. But the very fact of such a decision shows that the real Mongol aristocracy gradually urbanized and gradually broke with steppe customs and traditions. In the XIV century in the activities of the Chagatai khans there is a decisive turn towards the policy of the second direction, which meant a powerful wave of Islamization of the Mongols in the west.

A noticeable step towards centralism and subordination of tradition to Muslim culture and statehood was made in the reign of Kebek Khan (1307-1309, secondary in 1318-1326). Kebek put into circulation silver coins with the image of Khan, which can be considered as the first state coins of the Chagatai dynasty. In addition, the ulus undertook a massive construction and restoration of previously ruined cities (for example, the city of Balkh). Kebek Khan moved his headquarters from the Ili Valley to Maverannahr, where in the lower reaches of the Kashkadarya River he built the palace of Kharshi, which later became a major administrative center.

The Chinggisids’ move to the cities was considered a violation of the Yasa of Genghis Khan and every attempt to change the way of life caused a clash with beks (emirs) — the leaders of Turkic nomadic clans and tribes, which constituted a significant military force of the state. To attract to his side the representatives of the main clans of the ulus, Kebek Khan carried out a reform, which led to serious changes in the administrative and political management of the country. The territory of the whole country was divided into small administrative and tax districts tumen («ten thousand») headed by nomadic Mongolian-Turkic nobility. The main clans in Chagatai’s ulus, and there were four of them: Barlas, Jalar, Arlat and Huchin, received tumens first and in the best regions of the country.

Thus, with the transfer of the khan’s residence and the resettlement of the main clans of Chagatai’s ulus to Maverannahr, the process of the Chinggisids’ accession to the traditions of sedentary Muslim culture with all its institutions actually became irreversible. Muslim authors of that period glorify Kebek as a just sovereign and patron of Muslims, although he himself did not accept Islam and remained a follower of the faith of his ancestors until the end of his life.

After Kebek Khan’s death in 1326, a domed mausoleum of the Muslim type was built over his tomb.

Thereafter, the Chagatai state was ruled one after another by three brothers of Kebek Khan: Ilchigatai, Duran-Tumer and Tarmashirin. All of them strove to strengthen the state by introducing the political elite to the values of Islamic culture. In particular, Tarmashirin (1331-1334) actually turned Maverannahr into the administrative and political center of the Chagatai state. He adopted Islam and later declared it the official religion of the ulus. The Arab traveler Ibn Battuta describes his meeting with Tarmashirin in 1333 and points to the full compliance of the customs of the khan’s stake with the canons of Islam. In the foreign policy sphere Tarmashirin showed himself as a successful diplomat and military commander (in particular, his campaign to Delhi in 1332 is known).

After Tarmashirin’s return from the Indian campaign, the Chinggisids and noyons dissatisfied with the khan’s policy revolted against him. This rebellion was a kind of reaction of the clan aristocracy to the rapid Islamization, especially of the western part of the Chagatai ulus. The revolt was led by one of the Chinggisids, Buzan. Tarmashirin’s troops were defeated, he died in battle, and his men swore allegiance to Buzan.

Buzan (1334-1336), to all appearances, relied in his policy on representatives of the tribal Mongolian-Turkic aristocracy, as well as on a group of officials from among the Uighur Buddhists, who by that time actually usurped the functions of officialdom in the major cities of the state.

Around 1335 Buzan unleashed repressions on the Chinggisids and noyon-emirs of the ulus who had converted to Islam. Dissatisfied with this, the Muslims waited only for an opportunity to overthrow the tyrant. In 1335-1336 a rebellion was raised against Buzan and he was killed by one of his relatives Khalil, who had converted to Islam.

Khalil managed to strengthen the foundations of the state for a very short time, but in the early 40s of the XIV century the ulus was already actually disintegrating into two independent states.

In the west of the Chagatai ulus in Maverannahr, Muslim rulers eventually established themselves, and the Chagatai clan lost its dominance. In the east, in East Turkestan, representatives of the local clan aristocracy came to power and put Tugluk-Tumer Khan on the throne of Chagatai.

The state of East Turkestan is referred to in medieval sources in different ways: Ulus Mughal, Ulus Dzheti, but most often Mogolistan (Persian for «country of the Mughals»). The borders of this state gradually changed as it found itself surrounded by various hostile communities and its rulers had to wage constant wars with Kazakh khans, Ming China and their tribesmen from Fergana and Maverannahr.

During the XIV-XV centuries, the ethnic composition of the country gradually changed, and by the end of the century Mongols no longer constituted the majority of the population of Mogolistan. According to T. I. Sultanov, «the Mongols of Mogolistan were nomads who constituted the main military force of the country. In this sense, the Mongols were not a special ethnic group: among the Mongols of Mogolistan there were natural Mongols, who remained committed to the worship of Heaven, and natural Kipchaks — Muslim Turks, and other nationalities that retained nomadic traditions…» (20, p. 176). (20, с. 176). The inhabitants of Maverannahr, for example, called the inhabitants of Mogolistan dzhete (sute, a free man).

Thus, jete in the Eastern Chagatai ulus turned into socio-political and, most importantly, military support of the khan’s dynasty, which acted in relation to the indigenous population of the ulus (Kipchaks, Sarts, Taziks, etc.) as alien and invasive.

The first independent khan Tugluk-Tumer (1346-1363) with the support of the Jete subjugated Kashgar, Yarkend, and Uiguristan. He accepted Islam and together with him about 160 thousand of his supporters, most likely those «free people», accepted Islam. In the spring of 1360, Tugluk-Tumer decided to extend his power to the western regions of Chagatai ulus. However, despite temporary successes, emirs and beks of Maverannahr did not want to fall under the power of nomads from the east again.

In 1363 Tugluk-Tumer died and his heirs refused to recreate a unified Chagatai power. During the same period, Timur, the emir of the Shakhrisyab region (near Tashkent), strengthened in Maverannahr, whose name is associated with the creation of a new empire in Eurasia.