The Kipchaks began to penetrate into the Northern Black Sea coast in the middle of the IX century, but as an ethnos they appeared much earlier and were of Turkic origin. In the VIII century the Kipchaks were part of the Kimak Kaganate, created on the basis of seven tribes.

The Kipchaks appeared in Crimea between the end of the X and the beginning of the XI centuries. The appearance of the Kipchaks, who settled on the peninsula, practically did not differ from the appearance of the peoples who got there earlier and felt themselves indigenous. The Kipchaks who lived in the Crimea were distinguished by light eyes and hair the color of chaff, or rather straw. Their descendants with the same appearance are still found in significant numbers among the Crimean Tatars.

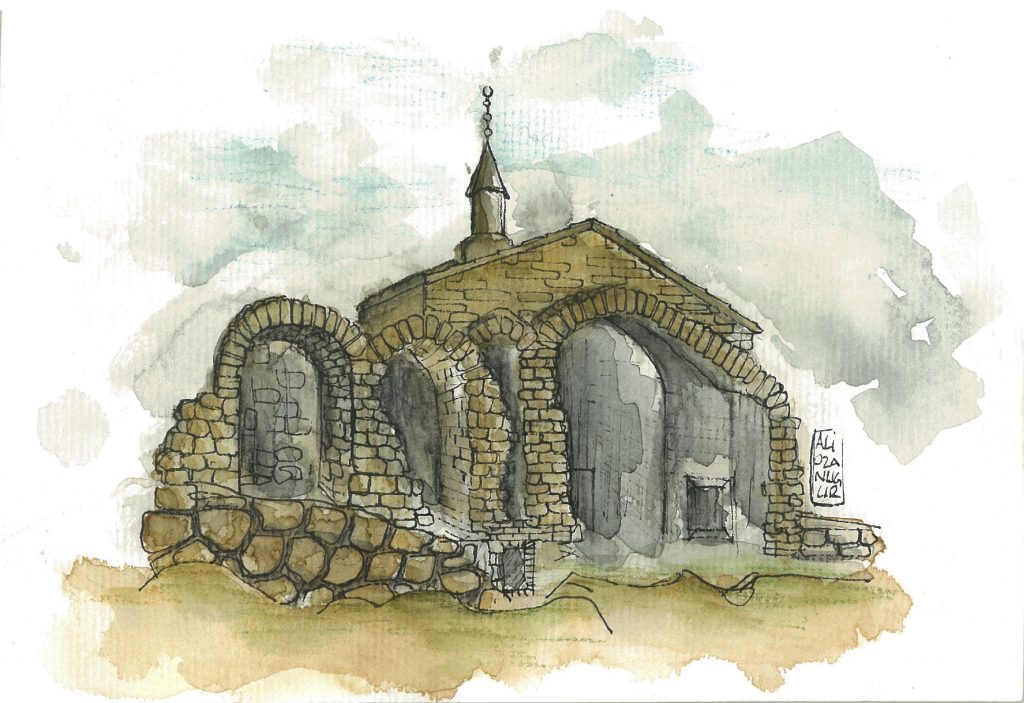

The Kipchak capital of the Crimea was Sugdeya, whose might and military power allowed them to repel and contain external enemies, as well as to keep subordinate territories in submission. Most importantly, the Kipchaks ensured the security of international trade.

In the middle of the 12th century, the Kipchaks were the majority in Crimea. This is confirmed by archaeological data and surviving documentary sources. The first information about the Kipchaks of the peninsula was written in the work of 1154, which was called «The Highwayman». The work belongs to the Arab geographer-traveler Isidi. In his book he wrote about Jalit (Yalta), located in al-Kumaniyya.

The Kipchaks ruled the Crimea until the appearance of the Mongol hordes in 1223. Subsequently, after some time the Kipchaks assimilated the few Mongols and other representatives of Turkic peoples who came with them.

The medieval historian El-Omari wrote that the Golden Horde was once a country of the Kipchaks, and the Mongol-Tatars gradually became related to them, taking their girls as wives. Relations between the Kipchaks and the Tatars soon improved. In many cities Kipchaks were appointed viceroys. So in Solkhat sat the viceroy — a Kipchak named Tabuk. Temnik Mamai was also a Kipchak. Their number was much higher than the number of newcomers of the Horde, so the Kipchaks became the basis for the formation of the Crimean Tatar ethnos.

The Kipchaks left a significant trace in the history of Crimea. Until 1944, there were many toponyms with the particle «Kypchak» on the peninsula. Unfortunately, nowadays the settlements have other names.

Even before coming to Crimea, the Kipchaks were engaged in agriculture. Having settled on the peninsula, they mastered new ways of cultivation, which were used by the local population. Leading a semi-sedentary lifestyle, the Kipchaks continued to breed large horned cattle, sheep, horses and camels.

Professional craftsmen began to emerge among the Kipchaks, who processed metal, furs, made boots, sewed clothes, made saddles and bows. Mass production of «stone babas» can be considered a separate type of craft. Talented stonecutters and sculptors, who were able to repeat the smallest details of their models’ appearance, even their clothes, made thousands of them in a whole network of workshops. Only noble kin of the Kipchak could afford exact copies of the deceased person, the less wealthy ordered simple sculptures. Several wooden statues have been preserved. In addition, stone statues of later times began to be painted.

Having carefully studied the history of «the largest of the Kipchak cities» — that is how Arab Elaini wrote about Sugdei — we can conclude that enterprising Kipchaks were skillful traders. In the center of the Crimean possessions of the Kipchaks, the economic interests of merchants from almost all over the world intersected. According to ancient documentary sources, fabrics, clothes, jewelry, weapons, spices, dates and incense were brought there, and in return foreign merchants purchased a variety of local products. Crimea prospered due to trade with China, India, Syria, Egypt, Western and Eastern Europe.

Ancient Kipchaks professed Tengrianism. The ruler of the Upper World and the supreme deity is Tengri, he determines the terms of people’s lives, but their births were «managed» by Umai, the goddess of fertility. The ruler of the Middle World and the supreme deity was the deity «Sacred Earth — Water» (Ydun Ier-Sub). The ruler of the Lower World was Erklig, who was in charge of the death of all living beings. In addition to the main deities, there were many minor deities, including the Sun (Kun) and the Moon (Ai), as well as totemism. For most Turkic tribes, the main totem was the blue wolf.

A special place in the beliefs of the Kypchak tribes was occupied by the cult of ancestors. It was expressed in the installation of stone anthropomorphic figures (so-called «stone women») near the burials of noble, honored men and women. The statues were placed on elevated places facing east. Statues (X-XI centuries) were made primitively, the image (drawing) of the face was schematic, later ones became more artistic and realistic. In the XI century Islam spread among the Kipchaks. First of all, Islam was accepted by the aristocracy and warriors.

There are known samples of oral folklore that came to Crimea together with the Kipchaks: tales about Leyla and Majnun, Yusuf and Zuleikha, «Ashik-Garib», funny stories about Khoja Nasreddin, etc. Many of such fairy-tale-legendary heroes are found in other Islamic countries, and they appeared on the Crimean peninsula because the overwhelming part of the Kipchaks were Muslims then. And also elements of oral folk art of the Kypchak period of the peninsula’s history have been preserved.

The high level of cultural development of the Kipchaks is evidenced by the presence of their own dialect, which became the basis for the formation of the official language of the Crimean Tatars. In the 12th century, the Kipchaks created the «Codex Cumanicus» — a dictionary with the help of which they could communicate with representatives of other countries. All ethnic groups of the Northern Black Sea coast had the opportunity to understand each other thanks to the Kipchak language.

«By the middle of the XIII century, the local population of Crimea spoke exclusively in the Turkic Kypchak language, a little later it would be known as Crimean Tatar. Venetian and Genoese merchants would call this language Kuman. Commercial, political and religious figures of Europe actively cooperated with the Kipchaks. All of them had to communicate with each other in the international Turkic language of the Great Steppe and Northern Black Sea region — Kipchak. So it became necessary to compile a dictionary or phrasebook to simplify communication. Such a dictionary-phrasebook appeared very soon — today we know it as «Codex Cumanicus». This unique written monument came out around 1294 from the pen of an anonymous author in the heart of Eastern Crimea — the city of Solkhat», — writes Gulnara Abdulayeva.

«Codex Cumanicus» is a literary monument of the Crimean Tatar language.

«Literature in the Golden Horde also existed in a literary language understandable to all its inhabitants, the so-called «Chigatai», based on the Kypchak layer — its Kypchak-Oguz dialect», notes K. Musaev.