The Mongol Empire (Khamag Mongol ulus), having arisen in the XIII century as a result of conquest campaigns such as the Mongol-Tatar invasion of the Caucasus by Tamuchen (Genghis Khan) and his descendants, in the heyday of the Middle Ages was actually the strongest state on the planet. As they would say now, a world power. Its borders stretched from the Carpathian Mountains in the west to the Amur and the Pacific Ocean in the east, from the Russian lands and Siberia in the north to Afghanistan, Iran and Iraq in the south. Organized on an advanced level with a system of military units and a strict hierarchy of commanders, and after capturing Northern China with its centuries of cultural and technical achievements and armed with perfect siege weapons, the Mongol army became virtually invincible in open combat.

In the early 13th century, the North Caucasus was inhabited by various peoples, who practiced cattle breeding and agriculture. On its steppe plains roamed the Turkic-speaking Kipchaks, called Polovtsians in Russian chronicles. The mountains and foothills of the Western Caucasus were inhabited by a numerous, but politically disunited ancient people of the Caucasus — Adygs (we have many publications about this people on history-thema.com). In the middle part of the North Caucasus was the once strong but now in deep decline Alanian kingdom. The lands of the North-Eastern Caucasus were inhabited by the Vainakh tribes and the peoples of mountainous Dagestan. The entire Transcaucasus was to a greater or lesser extent dependent on the politically and culturally highly developed Georgian kingdom, a strong and formidable state with which the Byzantine Empire reckoned in its foreign policy. In XII-XIII centuries Georgian army together with the armies of other peoples of Transcaucasia — Armenians and Azerbaijanis, forced the Seljuk Turks out of the Caucasus. After that the feudal lords of Armenia and Northern Azerbaijan recognized their vassal dependence on Georgia. Cultural and economic growth began throughout Transcaucasia. At such a moment, the Mongol court in the capital of the empire Karakorum, obsessed with the idea of bringing the whole world under its domination, became interested in the fertile Caucasian lands.

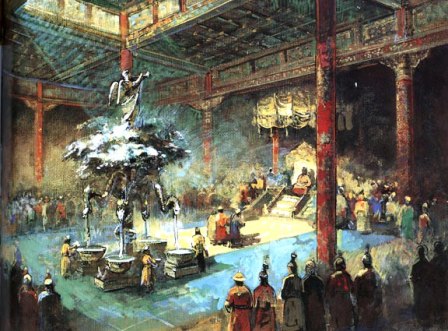

Reconstruction of the khan’s palace in Karakorum

Genghis Khan’s government did not organize a special campaign to the Caucasus. But in 1220 two tumen (the highest military unit of the Mongol army numbering about ten thousand people) under the command of Djebe and Subede, passing through the northern lands of Iran — a country with two thousand years of civilized history, and easily turning its flowery cities into burnt ruins, came to Azerbaijan. Full of strength and aspiration for new conquest, the Mongol armies rushed further. An eyewitness of the Mongol attack on Azerbaijan wrote that «the whole country was full of dead bodies, and there were no people to bury them». Having wintered near the Arax River, the Mongols moved to the Georgian kingdom. They were met by powerful Georgian-Armenian troops. After the fiercest battle, in which both sides suffered heavy losses, Dzhebe and Subede were forced to give orders to retreat. But the united Georgian-Armenian army was also severely damaged; Georgian king George IV died of wounds received in the battle.

How the Mongols ravaged the CaucasusThe Transcaucasus was then unaware of the size and power of the Mongol Empire, which had emerged quickly and unusually at that time. And the Georgian court made a mistake, which a little later repeated the Russian princes: considering that the attack of the Mongols was just a passing raid of an unknown steppe tribe, began to prepare for a crusade to Jerusalem. Meanwhile Djebe and Subede passed through eastern Azerbaijan to the north, ravaging everything on their way, capturing huge booty. When the Mongol army approached the narrow lowland passage between the mountains of the Greater Caucasus and the coast of the Caspian Sea, leading to the steppes of the North Caucasus, the ancient well-fortified city of Derbent, which three centuries ago was a border fortress of the Arab Caliphate, stood in its way. Genghis Khan’s soldiers could not take Derbent by storm and asked the besieged to send them some parliamentarians for peace talks. However, when the parliamentarians arrived at the Mongol camp, the conquerors seized them and demanded to show them the way around Derbent. The Mongol army moved through the steep Dagestan mountains, fighting fiercely with the battle-hardened local population, but still moving forward with determination.

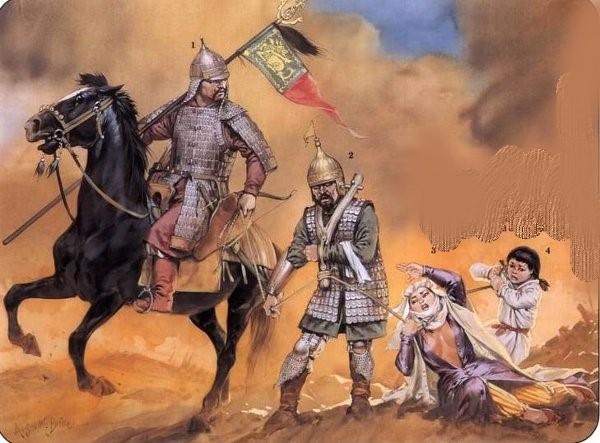

Having finally broken through the North Caucasian steppes, the Mongols found themselves in the lands of the Alanian kingdom. The North Caucasus had already heard about the military strength and cunning of the new enemy. A united Alanian-Kipchak army opposed the two tumens of Dzhebe and Subede. Secretly from the Alans, Mongolian parliamentarians came to the Kipchak khans and convinced them that the Mongols were not going to fight with the same nomads as them, the Kipchaks, but came to fight exclusively against the Alans. How the Mongols conquered the Kipchaks broke the alliance with the Alans, and Mongolian warriors attacked the Alanian troops left without support. Having completely defeated the Alanian army, the Mongols ravaged and turned to ruins the once mighty Alanian kingdom, which then ceased to exist. Some of the Alans were killed, some of them hid in inaccessible mountains, where they mixed with local peoples and became ancestors of the Ossetian ethnos. And the Mongols, having defeated the Alanian kingdom with amazing cruelty, suddenly fell on «the same nomads» Kipchaks and began to ravage their camps. Fleeing from imminent defeat, the Kipchaks fled from the Caucasus to the north-east — to the steppes of modern Ukraine, where they concluded a treaty with the princes of Kievan Rus against the Mongols. In 1223 the Mongols defeated the united Kipchak-Russian army on the Kalka River. During the years of endless campaigns, having lost many soldiers, worn out weapons and armor, needing rest and unable to replenish food supplies in the ruined lands, Dzhebe and Subede returned to Mongolia through the Volga region and steppes of modern Kazakhstan, where they reported to Genghis Khan about the rich lands they had discovered.

How the Mongols invaded GeorgiaThe Caucasus quickly forgot about the Mongol threat. Transcaucasia restored the economy destroyed by the invasion of the two tumens. The invasion of South Azerbaijan in 1235 by a huge Mongol army came as a complete surprise to its population and rulers. The confused feudal lords could not gather a united army and coordinate their actions, some of them were terrified of the invaders or disliked each other and joined the enemy’s side. Quickly the Mongols approached the capital of the Georgian kingdom Tbilisi. Queen Rusudan fled to Western Georgia and ordered to set the city on fire. The Mongol army entered the burning capital without a fight. The history of the peoples of the Caucasus has never known such devastation and bloodshed. Regular troops and feudal militias were defeated everywhere. Despite this, the ordinary population of the Transcaucasian countries independently armed themselves and put up a stubborn and desperate resistance to the invaders. The Mongols destroyed the cities of Ganja, Shemakha, Derbent, Ani and Kars, which did not want to surrender to them. Only after four years of brutal war Mongols were able to establish their power in Azerbaijan, seven years — in Armenia, and ten years — in Georgia. But even after the Transcaucasus was annexed to the Mongol Empire, the population that did not want to live in slavery of foreigners continued their fragmented struggle for decades.

What were the main centers of culture in the CaucasusIn 1237, an army sent by Genghis Khan’s grandson Batu, who had set out to conquer Volga Bulgaria and Russia, entered the North Caucasus from Kazakhstan. Within three years the Mongols devastated the North Caucasian steppes, the lands of Adygs, Alans and Dagestan. However, the mountainous strip of the Caucasus, where the population fled en masse to escape death, devastation or capture, proved to be an insurmountable obstacle for the Mongol warriors accustomed to the vastness of the steppe. Only after heavy losses could the Mongols gain a foothold on the most important strategic points of the Caucasus Mountains. The Caucasian population, having fortified itself in inaccessible mountainous areas, reorganized its economy and way of life under new conditions and fought fiercely against the invaders. At the same time, the now famous culture of the Caucasian mountaineer — a fearless warrior who does not take a step out of his home without a weapon and jealously guards the freedom of his native land — began to take shape.

The Caucasus was part of the huge province of the Mongol Empire — the Ulus Dzhuchi (Golden Horde), whose first khan was Batu. In the 50s of the XIII century Khan Hulagu annexed Transcaucasia to his ulus. Hulagu’s descendants, who ruled Transcaucasia, were called Ilkhans, i.e. rulers of the people. After the collapse of the Mongol Empire in the second half of the 13th century, both ulus became independent states and fought among themselves for the right to rule Transcaucasia.

The khans imposed heavy taxes and duties on the subject peoples, who had not recovered from the military devastation. All this led to the impoverishment of the population, the decline of crafts and culture, and the desolation of cities. Many ancient professions were forgotten and peoples returned to more primitive ways of economic activity. The entire Caucasus was constantly shaken by uprisings against the khan’s authority and viceroys. They were brutally suppressed, but flared up again and again. In the 60s of the XIII century after suppression of rebellion in Azerbaijan by Ilkhan, travelers saw hundreds of versts of burned gardens, after which this area was nicknamed «Kara Bakh — black garden». The population also suffered from the devastating wars of khans among themselves. The invasion of the Central Asian Emir Timur shook the entire Caucasus from the Don to the Arax like the Mongol invasion itself.

After the final fall of the Ilkhan state, various small nomadic rulers continued to seize power in Transcaucasia: descendants of Timur and Turkmens who also came from Central Asia. Local peoples could not recover long enough to take power in their native land into their own hands again. Georgia at the end of the 15th century disintegrated into separate kingdoms and principalities and did not have political independence until 1991. In the North Caucasus, the peoples driven into the mountains by the conquerors developed an independent mountain culture. Many of them, in particular the Adygs, began to lead a semi-nomadic way of life, spending the winter in the valleys, and in summer going up with flocks of sheep to high-mountain pastures, where nomadic warriors could not reach.

The most famous Caucasian costume — the Circassian caftan — appeared in the everyday life of most Caucasian peoples. It is a locally adapted, comfortable both on mountain pastures and in battle, resemblance to the Mongolian caftan. With the spread of firearms, special cartridge holders — gazyri — began to be sewn on the front.