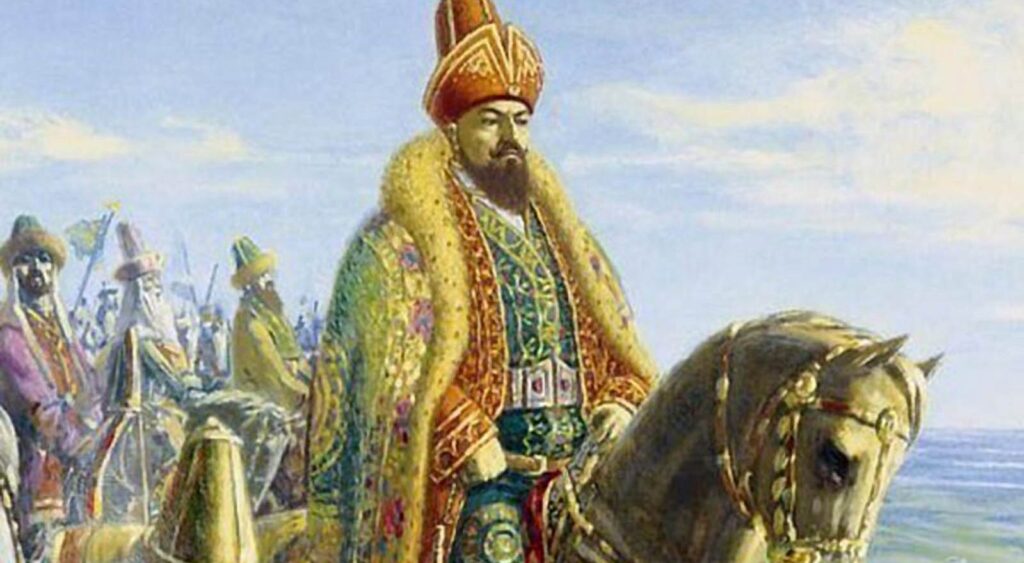

The XVIII century entered the history of the Kazakh people as the era of Ablai. Among his contemporaries such remarkable figures as Tole-bii Alibekov, Kazbek-bii Kazdauisty, Kart Kanzhigali Bogenbai, Abulkhair, Barak, Zholbarys, Abulmambet (1739-1771) and many others stood out for their talents. However, even among them Abylai’s versatile gifts made his figure a key one. Abylai’s multifaceted talent was especially brightly revealed during the struggle of the Kazakh people against the Dzungar and Qing conquerors.

Abulmansur was born in 1713. He was an orphan early, it is noted the fact that he under the name of «Sabalak» in ten versts from Tashkent in the place Karakamys in 1725 passed the camels of Tole-biy.

In XVI-XVII centuries had to face a very serious opponent — Dzungarian Khanate. In the XVII century between the squads of Kazakh rulers Esim, Dzhangir, Tauke, on the one hand, and the armies of Dzungarian khans — Batur, Senge, Galdan — on the other, repeatedly battles took place. Since 1709 began a wide invasion of Dzungar feudal lords in Kazakhstan, retaliatory strikes of Kazakh druzhiny and militias against the invaders.

In the spring of 1723, having concluded a truce with the Qing Empire, the Dzungar armies suddenly invaded the Kazakh nomads. One of the fiercest Dzungar-Kazakh wars of the XVIII century began. In this war and showed himself twenty-year-old Abulmansur, who defeated the Dzungar Bahadur Sharysh. He amazed all the batyrs who had seen the sights with unusual boldness and courage. «In this terrible and bloody time — believed Ch. Valikhanov, — draws everyone’s attention Sultan Ablai. Participating in all the raids, first as an ordinary warrior, he shows feats of extraordinary bravery and cunning. His useful advice and strategic considerations strengthen the name of wise». On his legendary horse Chalkuyruk under the war cry «Ablai» he alone rushed to the hoards of enemies and managed to stay alive in the fierce battles. Repeatedly the young man before the fight went to duels with Dzungarian Bahadurs and defeated them. At the same time even then Ablai showed outstanding military abilities in the organization and implementation of military operations. His sound advice and suggestions to military commanders Abulkhair, Bohembai and others helped to find the right solutions in difficult situations. Then Abulmambet marks Abulmansur, and when he learns that Abulmansur is a tore and the son of Baky Vali and grandson of Ablai himself, then with the approval of 90 of the best representatives of the three zhuzes, a blessing from a man named Zhanibek, Abulmansur was elected sultan.

The war of 1723-1729 ended with the victory of the Kazakh militias. However, the ruling class of Kazakh society, due to internal strife and disagreements, did not take advantage of the political fruits of this victory. It is natural that Ablai due to his youth could not have any influence on political events on the scale of the whole khanate. His military talents and unconditional personal courage put him on a par with famous batyrs, and his sultan origin and the vicissitudes of fate that he experienced ensured the patronage of influential people — Abulmambet and Bohembai. Soon he became the head of one of the numerous and strong clans — Atagai of the Argyn tribe of the Middle Juz. Having the strength and the number of tribesmen supporting him, as well as the wealth of his herds, the presence of certain abilities, Ablai by the end of the 30s had already advanced to the number of the most influential people in the steppe. From the very beginning of his political activity the young sultan showed himself to be an intelligent and flexible ruler. He understood well that in the conditions of the Dzungars’ conquest of southern trade centers and sedentary-agricultural oases in the Syr Darya basin and the preservation of a serious military danger on the south-eastern borders of the Kazakh Khanate, the priority foreign policy task for the Kazakhs was the possibility of spreading their nomadic places to the north and north-east of the region and establishing a stable trade exchange with Russia for various products and goods. To this end, he decided to follow the example of Abulkhair Khan and on February 28, 1740 officially accepted in the Orsk fortress together with the Khan of the Middle Juz Abulmambet Russian citizenship.

In 1735 Galdan-Tseren (1727-1745) subjugated the Elder zhuz. Four years later, in 1741, having signed peace with China, Dzungar feudal lords transferred their armies to Kazakhstan and invaded the Middle Juz. Khan Abulmambet could not organize proper resistance to the invaders and had to flee with the rest of his men. Sultan Ablai took upon himself the organization of resistance. Thanks to his energy and perseverance auls and cattle were sheltered in safe places, and the enemy, despite the significant numerical superiority, suffered losses from unexpected blows of Kazakh druzhiny.

Kazakh rulers, despite a number of heavy defeats, still managed to get away from defeat. The war began to take a protracted character. The vicissitudes of the war, however, were such that Ablai during the reconnaissance got into the center of the location of the Dzungarian troops and was taken prisoner. The war, in fact, ended with the defeat of the Middle Juz.

The years he spent in the Dzungar captivity were not without a trace. He saw visible manifestations of the coming crisis in the Dzungarian state, understood for himself the strengths and weaknesses of this khanate, learned the Dzungarian language, won the favor of many Dzungarian aristocrats. Unlike some other representatives of the Kazakh nobility, Ablai behaved honorably in the Dzungarian walls. In captivity he shows resourcefulness, his pride and self-esteem are brightly manifested. All this was appreciated by his opponents. The fact that the Dzungarian khan Galdan-Tseren signed a peace treaty between the Middle Juz and Dzungaria with his noble prisoner, and not with Abulmambet, is remarkable in itself. In other words, the Dzungarian khan recognized him as the owner of the Middle Juz. Indeed, after returning to his nomads from the Dzungarian captivity, which was facilitated by the Russian government and the local Orenburg administration in the person of I.I. Neplyuev, Ablai became the de facto ruler of the Middle Juz. The power of Abulmambet Khan from that time onwards was of a completely prosaic nature. All embassies and messages from neighboring countries are sent henceforth either directly to Ablai, or to Abulmambet and Ablai.

In 40-50 years of VXIII century Sultan Ablai managed to strengthen his positions in the Middle Juz and expand the sphere of his own influence among the nomads of Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Kazakhstan. This was facilitated by his successful military leadership during the new Oirat-Kazakh wars. During the selfless struggle of the Kazakhs against the next military aggression of the Dzungars, Ablai’s great organizational talent, strong will and foresight, his ability to organically combine military and political methods of solving urgent issues, as well as to correctly determine external priorities in solving complex military and political problems were fully revealed. It is not by chance that it is to this period of the military biography of the famous khan that historical plots of many Kazakh folk legends about Ablai go back, telling in bright colors about his exploits on the battlefield and confrontation with the famous Dzungarian khan Galdan-Tseren.

Acting assertively and decisively against external enemies on the south-eastern border of Kazakhstan, the young sultan at the same time took a neutral position in relation to the internecine struggle of influential Chingizid clans for supreme power within the Kazakh Khanate and showed caution and foresight in this sensitive issue. Formally being a client of Abulmambet Khan of the Middle Juz, he clearly demonstrated before the Kazakhs and the Russian government his almost filial deference to his direct patron and at the same time showed a respectful attitude to Abulkhair Khan.

During the latter’s life Ablai clearly distanced himself from his main enemy, Sultan Barak, and after the tragic death of the Khan of the Younger Juz in 1748, he severely condemned the murderer and offered the family of the dead Khan his help in implementing the plan of blood feud. This far-sighted and pragmatic line of behavior in the complex internecine struggle between nomadic leaders of the region allowed Ablai to provide the necessary support and friendly attitude to himself from the ruling elite of the Younger Juz and at the same time contributed to the transition under his patronage of a large group of tribes Uak, Kerey and Kypchak, formerly under the control of Khan Abulkhair.

Ablai’s active participation in the struggle with the Dzungars in the «Years of the Great Calamity», the valor he showed, put him among the rulers who had more and more influence on the foreign policy of the khanate, first of all the Middle Juz. Helpless and indecisive Abulmambet from the first years of his reign did not solve any issue of principle without consultation and advice of Ablai. Already by the end of 30th years Ablai, relying on the strength of numerous Atagai family, support of famous batyrs, became the second after the khan person in the Middle zhuz. It is not by chance that he together with Abulmambet signed a treaty recognizing Russian citizenship.

In the mid 50s of the XVIII century, when in the neighboring Dzungarian Khanate there was an acute dynastic crisis, and began a bloody internecine struggle around the khan’s throne, Sultan Ablai took a very active part in these events and showed himself a subtle ruler and skillful politician.

Included in the internecine strife of the Oirat princes on the side of rebellious noyons Davatsi and Amursana, he was able to exhaust the warlike Oirats by the hands of their own tribesmen, and as the military action on the northern borders of the Dzungarian Khanate developed, he was able to advance the nomads of the clans and tribes under his control in the valley of the upper reaches of the Irtysh and Zaisan hollow. In 1756, when the Manchu army of many thousands dealt a crushing blow to the Dzungar nomads, Ablai withdrew his troops from the Oirat domains and went to the side of the Qin. According to the correct definition of A.I. Levshin, «having changed allies, he did not change his goal and tried in the new situation to spread the nomads of Kazakhs of the Middle and Elder zhuzes to the areas of Tarbagatai and North-West Semirechye, formerly under the jurisdiction of the Dzungarian khans.

After the conquest of Dzungaria by the Qing troops in 1755 and the almost total extermination of the Oirats by the Manchu army, the Middle Zuz found itself in extremely difficult geopolitical conditions. In this situation, not only military talents, but also great intelligence, self-control, endurance and outstanding diplomatic abilities of Ablai were most clearly and fully manifested.

At the same time, one of the pretenders to the royal throne, an ally of Abylai, noyon Amursana, having learned about his assassination prepared by Beijing, raised an anti-Qing rebellion and turned for help to Ablai. The latter supported Amursana for several years, which led to the invasion of the Qing armies into Kazakhstan in 1756 and 1757. At the same time, Qing diplomacy made considerable efforts to ensure that Ablai refused to support the liberation movement of the peoples of Central Asia. Kazakh feudal lords sought to have a weak Dzungaria as their neighbor, rather than the powerful China. Only in the middle of 1757, after the final suppression of the rebellion in Dzungaria by the Qin and Amursana’s flight to Russia, Ablai made a truce with the Qin command and established diplomatic relations with Beijing. Formally remaining faithful to his oath of eternal allegiance to the Russian throne, Ablai at the same time went with Abulmambet’s son Abulfayz to Beijing and entered the Chinese emperor’s allegiance as a «vassal prince», actually retaining full independence, but paying the agreed tribute. Later he subtly and diplomatically used his dual status as a subject of the Russian and Qing empires in relations with both patrons to successfully pursue his own policy in the Kazakh Khanate.

In the 60s of the XVIII century, under the conditions of preservation of formal power in the Middle Zhuz of the elderly khan Abulmambet, Sultan Ablai already had real political power over the majority of nomadic units of Northern, Central and South-Eastern Kazakhstan. According to A.I. Levshin’s characterization, «surpassing all modern Kyrgyz owners by years, cunning and experience, famous for his intelligence, strong in the number of people under his control and famous in the hordes for his relations with the Empress of Russia and the Chinese Goddikhan, he combined all the rights to the rank of the lord of the Middle Horde».

In 1756 Ablai concluded a treaty with Russia, but he did not perceive as legitimate the decision of the tsarist government of October 22, 1778 to grant him the title of Great Khan and did not go to the solemn ceremony, where he was to be given the appropriate act, coat and saber. Ablai believed that he had been elected by the people, which found international recognition from China, and therefore he should not swear allegiance to the Russians. If China does not encroach on his khan’s dignity, then the ceremony of swearing to Russia infringes on the sovereignty of the Kazakh khanate — this was Ablai’s position.

Like Abulkhair Khan, Ablai sought to unite under his rule the Kazakhs of all three zhuzes and to achieve economic and political domination of the Kazakh khanate in the Central Asian region. For this purpose, Ablai, like Abulkhair three decades ago, put his numerous sons, brothers and nephews at the head of the largest tribal units of Kazakhs, firmly and consistently suppressed clan separatism of noble elders, «he himself judged the guilty in unruly auls and himself and his tulenguts massacred them». To suppress the resistance of local nomadic elite Ablai often used military force and repeatedly tried to appeal for support to Russia and the Qing Empire.

Active embassies and trade relations of Ablai with the Qing court, strengthening of statehood in Kazakhstan, sharply increased the authority of the Kazakh khanate and the role of Ablai himself in the political life of the peoples of Central Asia. East-Turkestan khodzhas appealed to Abylai for help in the fight against the Qing Empire, in the early 60s, the ruler of the empire Durani Ahmad Shah tried to enlist his support. The ruler of the increasingly strengthening Kokand bekdom and other smaller rulers sought contacts with Abylai.

In the field of diplomacy, Abylai’s extraordinary abilities as a flexible and purposeful politician were also clearly revealed. Abylai, realizing how incommensurable the power of Russia or China with the Kazakh khanate, sought to maintain normal interstate relations with both empires, using the latter as a trump card in the fight against their internal opponents, as well as in wars against Kokand, the Kyrgyz manapas.

In 1771 the khan Abulmambet died. In this connection in the city of Turkestan in the mosque of Khoja Ahmed Yassawi took place the official election of Ablai to the khans of the Middle and Senior zhuzes, despite the presence of direct descendants. This event was later described by the captain of the Orenburg provincial command Mikhail Brekhov, who visited the summer residence of Ablai: «He, the Sultan, acquired the khan title in 1771 with the general consent of the sultans, elders, bai and ordinary people, as well as Tashkent and Turkestan, with the fact that he should be in charge over the entire Kazakh land and its people». At the same time, in 1776, in his written petition to the Russian Empress Catherine II on the approval of the khan title, Ablai justified the legitimacy of his rights to the title of «chief khan» by referring both to the universality of his recognition by Kazakh sultans and elders, and to the continuity of his inheritance of this highest rank from the khans Abulkhair and Abulmambet. He is officially recognized by Beijing, St. Petersburg, rulers of neighboring possessions. In fact, the power of the new khan, as well as that of his famous predecessors, had certain limits of penetration into the genealogical structure of Kazakhs, and extended only to the population of the Middle Juz and a significant part of the clans of the Elder Juz. This, in particular, is quite definitely evidenced by many lines of letters of Ablai Khan himself in 1778-1780, as well as competent testimony of representatives of the Siberian frontier administration of that period, who closely monitored the internal political situation in the northern regions of the region.

Sultan Ablai acquired the title of khan in 1771, but only in 1776, yielding to the persistent requests of his and his relatives, appealed to the Russian empress with a request to approve him as the supreme ruler of all three zhuzes. Relatively easy concession of the khan in this matter was dictated not only by his desire to be the official sole khan, but first of all and mainly by his desire to receive from the local administration Russian regular troops for the subjugation of the Tien Shan Kirghiz and sedentary population of the cities of the Syr Darya region, which were in the sphere of geopolitical attraction of the rapidly strengthening Kokand bekdom. For the first time the request to send Russian troops was stated by Ablai in one of his letters to the Orenburg governor, Major-General I.A. Reinsdorp on November 24, 1769 and since then for 12 years was the main topic of his correspondence with the central and local officials of Russia. Confirmation of the fact that this very purpose was the main reason for Ablai’s appeal to Empress Catherine II can be served by the remarkable fact that the Kazakh khan conditioned his agreement to arrive at one of the border fortresses to accept an affirmative letter and symbolic signs of his khan’s dignity from representatives of the Russian administration in his letters to the Russian Empress, Orenburg and Siberian authorities, the possibility of providing him with a «military team» for a campaign in South Kazakhstan and neighboring Kyrgyzstan.

The tsarist government, which had long ago appropriated the right to authorize the election of khans in the Younger Juz, was pleased with Ablai’s appeal to be confirmed as khan. But since St. Petersburg’s calculations did not include the strengthening of the institution of the senior khan in the Kazakh society, Empress Catherine II, on the recommendation of the College of Foreign Affairs, approved only the title of khan of the Middle Juz. At the same time, the tsarist authorities considered Ablai’s persistent requests and petitions to send Russian troops not only practically useless for their geopolitical purposes, but also very indecent for a «loyal subject» of the Russian Empire. Therefore, Ablai was categorically refused to fulfill this request.

Judging by the content of the Kazakh khan’s letters to the Russian authorities, the recognition of him by the Russian empress as a mere khan of the Middle Juz instead of the highest title did not make any noticeable impression on Ablai. However, the firm refusal of the tsarist authorities to send Russian troops to him in the steppe caused considerable irritation to the Kazakh ruler. Well aware of Ablai’s political plans, his personal clerk Yaguda Usmanov characterized the reaction of his master: «Ablai Khan would go not only to the Peter and Paul fortress, but also to Orenburg, if the troops he asked for were given, but without that he does not want to take not only an oath, but also signs.

Under various plausible pretexts, Ablai refused to come to the Peter and Paul Fortress to confirm his oath of allegiance to the Russian throne and receive monarchical symbols, and some time later he migrated with a large group of nomads under his control to the south of the region, in the Prisyrdarya steppes.

Later in Orenburg it became known that Ablai appealed to the government of the Qing Empire with a similar forgiveness, and in the spring of 1779 sent his son Syzdyk-sultan to Beijing to the Chinese Goddikhan with a request for military assistance.

However, in this case, as well as in the situation with the Russian Empire, Ablai was greatly disappointed. In June 1780, an experienced Orenburg official, collegiate registrar Mendiyar Bekturin, who was in the Kazakh steppe for reconnaissance purposes, on his return to the border line reported to the local administration, that Ablai’s son was «returned from the Chinese court with such a reprimand, from which he, Ablai, intended to take the liberty to subdue the Kyrgyz subject to the Chinese court, and therefore his request, Ablai, in the demand for troops is left without any respect.

In the end, Ablay managed in the fall of 1779 with the help of his military cunning and ingenuity to successfully conduct by his own forces a military campaign against the Tien-Shan Kyrgyz, as well as to win in the struggle with the rulers of Fergana part of the Prisyrdarya towns in the vicinity of Turkestan and Tashkent. However, as an experienced commander and politician, Ablai understood well that without the constant presence of regular military formations in the conquered places, he would not be able to keep the local sedentary population under his administrative and political control for a long time, and his domination in the southern part of the region would soon cease. Therefore, he saw the need to receive Russian and Qing troops not so much for the successful implementation of his conquest campaigns against the Sarts and Kyrgyz of the Prisyrdarya region, but rather to use them as a symbol of his supreme international prestige in the Central Asian region and an effective means of moral and psychological pressure on the rulers of Central Asian states.

Meanwhile, by the beginning of military operations in the Kyrgyz nomads under the command of Ablai there were about 2 thousand ordinary Kazakh warriors and batyrs. But already in the spring of 1780 after the completion of the operation in the region, «the warriors who were with him left for their uluses», and the khan was left with «no more than two hundred men», who could not serve as a solid support for the khan’s power in the conquered region.

The Orenburg authorities, who carefully observed through their agents the political situation in the Kazakh nomads, in the summer of 1780 came to a firm conviction that it was inexpedient to make further attempts to oppose Ablai with influential rivals from the Kazakh sultans. In the report of the Orenburg governor I.A. Reinsdorp to the College of Foreign Affairs of June 30, 1780 it was directly stated that in the current situation there was no longer any need to exert even indirect pressure on Ablai, as his limited ability to influence the political life in South Kazakhstan gave reason to hope for its imminent return under the state protectorate of Russia.

This expectation of the tsarist authorities was partly justified in the near future. In October 1780, Yaguda Usmanov, Ablai Khan’s personal clerk, who came from Turkestan to the Steppe and then to Orenburg, informed the local authorities about the results of the recent communication with the Khan and his elder sons. Children of Ablai Sultans Vali, Chingiz and Ishim assured that their father was soon going home, back to the steppe.

In October 1780, Ablai himself sent a message of similar content to Omsk to the Siberian governor D.I. Chicherin. In a laconic letter he recommended the Russian authorities to solve in his absence all important issues concerning the Kazakhs of the Middle Juz with his eldest son Vali-sultan (died in 1821) and at the end of the message quite definitely stated: «And I will be at home for the next spring».

However, in the summer of 1780, after returning from a victorious campaign against the Kyrgyz, Ablai’s health deteriorated, and he faced the question of succession to the throne in the Kazakh khanate in case of his premature death. Unlike Abulkhair, who sought to consolidate the ethno-social unity and territorial integrity of the Kazakh khanate through the transfer of the full power of the highest title to only one son, Ablai went to solve this extremely important problem in the traditional way. He bequeathed to his immediate descendants to divide power between his two eldest sons according to the principle of the old ulus system, founded by Genghis Khan.

According to the testimonies of tsarist officials of the 80s of the XVIII century, based on the direct testimony of the sons and closest associates of the senior khan, Ablai divided his ethno-territorial possessions between them as follows: «The whole Middle Juz got his son Vali, and the other — Adil-sultan — received a part of the Senior Juz in his power».

A kind of political testament of Ablai to the Russian authorities was his personal letter to the Siberian governor D.I. Chicherin, received in Omsk on October 26, 1780 a few days before his death. In this last message to Russia, the famous ruler and warrior — batyr wrote to the head of the Russian administration of Siberia: «Last year I left my nomadic area to fight with wild Kyrgyz, which I pacified and subdued. I also brought the Tashkent and Karakalpak towns into submission. And now I am in prosperity with my subject people.

But, though I am far away now, but my house and my relatives remained in the former place…. If my son will be offended and oppressed by Kazakhs from outside or from your side — from Russians — what offenses there will be, I ask you to protect him…».

When in the distant cold Tobolsk was received, as it later turned out, the farewell letter, Khan Ablai had already found his eternal rest under the high arches of the famous mosque of Khoja Ahmed Yassavi in the holy city of Turkestan. Together with him, the heroic era of Kazakh chivalry, marked by many big and small victories over the external enemy and great accomplishments of people’s batyrs, imperceptibly passed into the past.

Battle feats, military art and wisdom of Ablai Khan were sung by the best poetic talents of his epoch — Bukhar-zhyrau Kalkamanov, Tatikara, Umbetey-zhyrau and other folk storytellers. In the tolgau created on the death of Ablai, Bukhar-zhyrau, in particular, said:

You forced numerous Kalmyks to obey you,

You decorated your faithful battle axe with gold,

You fed your horses with rye, you raised their strength,

And over the whole vast steppe your spirit raged like a thunderstorm.

Despite his advanced age, Abylai not only organized a number of military campaigns in Central Asia, but also took an active part in the struggle for Tashkent, other polities of the Syr Darya basin, for nomads in Semirechye.

He managed to unite all Kazakh lands, including Tashkent, into one whole, and associated further plans with cultural and economic progress, considering, in particular, an alliance with Russia as a basis for the transition of Kazakhs to sedentary farming and commercial activity. These plans of Abylai met with opposition. As before, centrifugal motives, which had a devastating effect on the fate of the Kazakh people, acted. Even during the military campaigns of 1725-1726 it was possible to end the Dzungar threat, if Abulkhair had not left the battlefield and went to the north-west, where he accepted Russian subjection.

The same conservative and ambitious forces forced Abylai to resign. He goes to the Elder Juz, and in May 1781 dies in Tashkent. Abylai Khan was buried in the shrine of the Kazakh people — the mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yassavi.

For fifty years of his reign in the rank of both sultan and khan Ablai managed to strengthen for some time the structure of khan’s power in the central and south-eastern regions of the steppe, and gained great authority among the Kazakh population of the three zhuzes. According to Ch. Valikhanov, «Kazakhs considered the incarnate spirit (aruakh) sent down to accomplish great deeds». This can be confirmed by the widespread existence among the nomads of the region in the middle of the XVIII century — the beginning of the XIX century many different legends and epic tales about Ablai, preserved to this day in the historical memory of the Kazakh people.

At the same time, from the point of view of conscious choice of geopolitical priorities and long-term development strategy of the Kazakh society, the target settings of Ablai’s foreign and domestic policy were characterized by certain limitations and contradictions, lack of strategic vision of the main civilizational vector of development of the peoples of intracontinental Eurasia in the cultural and historical conditions of the new time.

The political course pursued by him on integration of the main part of Kazakh tribal groups under the authority of one khan was not continued under Ablai’s immediate successors, as it was implicitly oriented on harmonization of his personal interests with the most urgent social needs of Kazakh nomads at that time, but at the same time did not determine the guidelines of development for the Kazakh society itself for a relatively long-term historical perspective.

The political will of Ablai to his sons about the division of his power in the Kazakh khanate between the main heirs can be considered indicative in this sense. The outdated principle of succession to the throne laid down in it actually drew a chronological line under the relatively high level of centralization of power and socio-political integration of Kazakhs of the Elder and Middle zhuzes achieved by Ablai and once again actualized and legitimized clan-regional separatism of nomads subject to the older sons of this khan. As a result, a new impetus was given to the development of centrifugal tendencies in Kazakh society and further deepening of internal differences between its constituent ethno-territorial segments, because almost immediately after the death of Ablai Khan, they were divided into spheres of influence between Qing China, Kokand Khanate by Russia and then entered for several decades, up to the 70-80s of the XIX century in the zones of power, cultural, economic and spiritual attraction of the three different poles of the geopolitical space of Central Asia.

In his quite natural and legitimate desire to minimize the political dependence of the Kazakh Khanate on both the powerful Russian Empire and the Tsinov Empire, Ablai more or less successfully pursued for almost 25 years a two-vector foreign policy in the region, but on the slope of years had the opportunity to make sure of its rather limited mobilization potential. However, hesitating until the end of his days to make the main choice between the two poles of «great power» in favor of the most promising for the Kazakhs civilizational perspective, he, in fact, hopelessly tried to combine in the social practice of nomads conservative traditionalism with the needs and values of European modernization, i.e. to combine the incompatible.

This strategy was not crowned with the achievement of stable and long-term positive results for the Kazakh society and turned out to be unviable in its specific socio-historical consequences.

Conclusion.

After history and personal destiny, Ablai became the last khan who claimed seniority in all three zhuzes of Kazakhs. After his death, as a result of active involvement of the most influential nomadic leaders of the region and tribal groups of Kazakh society under their control in the sphere of geopolitical interests of Russia, Kokand and China, the almost three-centuries-old tradition of existence of the institution of the senior khan in the Steppe finally ceased. From that moment, a complex process of long-term transformation of the traditional system of power in the Kazakhs of the Younger and Middle zhuzes under the influence of Russian state institutions was clearly outlined.

Thus, the Kazakh Khanate played a huge role in the international life of Central Asia and Siberia in the 18th century. The rulers of both small dominions and powerful empires reckoned with its power and influence, striving to maintain normal ambassadorial and trade-economic relations with it and to use it in the struggle against their opponents. Ablai played in this period the main role in strengthening the international prestige of the Kazakh Khanate, this is another of his historical merits to the Kazakh people.