Western Campaign: Why the Sons of Choros Needed the Steppes of Desht-i-Kipchak

The lands stretching west of the Tarbagatai and Altai mountain ranges always attracted the Oirat leaders. It was not a blind thirst for conquest, as their neighbors, who suffered from nomadic raids, might have described it. For the Dzungar Khanate, the last remnant of the once mighty Mongol Empire, the question of expanding their living space was as sharp as a saber blade. Nomadic cattle breeding, the basis of the Oirats’ economy, required vast pastures, which were catastrophically lacking in their traditional territories. Each new herd of horses, each new flock of sheep increased the burden on the meager lands of Dzungaria. It seemed that nature itself was pushing them westward, to the boundless steppes of Desht-i-Kipchak, which belonged to the Kazakh tribes.

The rulers of Dzungaria, starting with Khara-Khula and his son Erdeni-Batur, the founder of the khanate in 1635, saw the Kazakh lands as more than just pastures. They were the key to controlling sections of the Great Silk Road, which promised considerable profits from transit trade. Caravans loaded with silk, tea, porcelain, and other exotic goods could fill the khan’s treasury, allowing him to maintain a powerful army and strengthen central authority. In addition, the subjugation of the Kazakh tribes would mean the elimination of a troublesome neighbor, who himself occasionally raided the Oirat nomads, stealing livestock and people. In the eyes of the Dzungar noyons, the Kazakhs appeared to be an undisciplined mass, torn apart by internal strife, and therefore easy prey. History would show that this assessment was not entirely accurate and would play a cruel joke on the Oirats more than once.

Moreover, expansion to the west was seen as a way to consolidate the Oirat tribes themselves—the Choros, Derbets, Khoshuts, and Torguts. A common enemy and joint military campaigns were supposed to unite them around the figure of the khuntaiji, the supreme ruler. The idea of restoring Genghis Khan’s Mongol Empire, albeit in a truncated form, continued to excite the minds of the Oirat nobility. It is likely that the Dzungar military leaders instilled in their vassals the idea of restoring former greatness and that the Kazakhs were merely an obstacle on this path.

The religious aspect should not be overlooked either. The Dzungars were zealous adherents of Tibetan Buddhism of the Gelug (“Yellow Hat”) school, while the Kazakhs professed Islam. For the Oirat lamas and rulers, spreading the “true faith” to the “infidels” was a pious undertaking. Although religious fanaticism was not the main driving force behind the wars, it undoubtedly added to their ferocity and justified the Dzungars’ conquests in their own eyes. The Dalai Lama of Lhasa, a spiritual authority for the Oirats, repeatedly blessed their campaigns, seeing the Dzungar Khanate as a pillar of Buddhism in Central Asia.

Thus, the Dzungars viewed the Kazakh steppes with the pragmatism of predators, aware of their strength and seeing their neighbors not only as a source of prey but also as a geopolitical target. It was a mixture of economic needs, imperial ambitions, the desire for internal stability, and religious zeal. They did not consider themselves aggressors in the pure sense; rather, they saw themselves as a force bringing order and restoring what they believed belonged to them by right of strength and as heirs to the great steppe tradition. The first major clashes, which began in the first half of the 17th century, were merely a trial of strength, a reconnaissance in force before the storm that would break out in the following century. Erdeni-Batur, and then his successors, methodically prepared the ground for a decisive push westward.

The iron fist of the Khuntaiji: the military machine of Dzungaria and its goals

By the beginning of the 18th century, the Dzungar Khanate had become a formidable military power that had to be reckoned with not only by the Kazakh zhuz, but also by the powerful Qing Empire and even distant Russia. The secret of the Oirats’ military successes lay not only in their natural belligerence and excellent cavalry, but also in the skillful organization of their troops, the adoption of advanced military technologies, and strict discipline. The Khuntaiji, the supreme rulers of Dzungaria, such as Galdan Boshogtu Khan and then his nephew Tsavan Rabdan, paid paramount attention to the army. They understood that only by force of arms could they keep vast territories under control and force their neighbors to pay tribute.

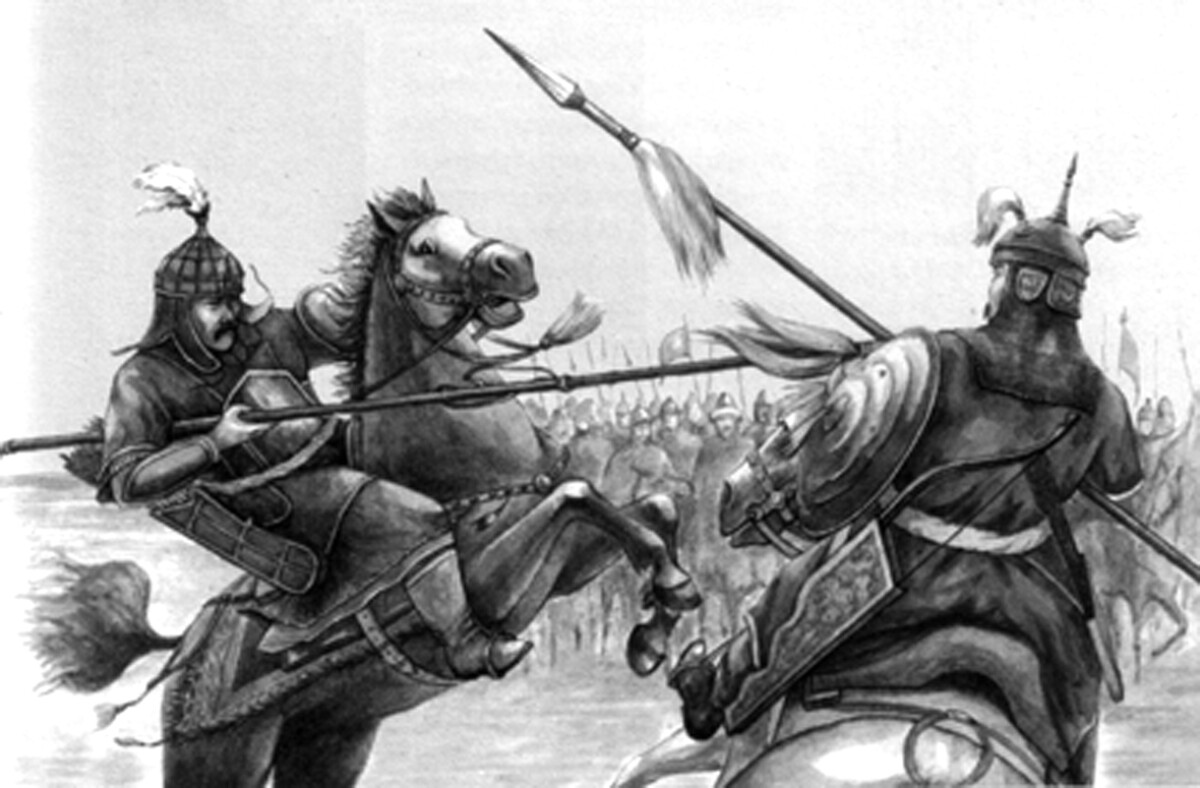

The core of the Dzungar army was cavalry armed with bows, sabers, and spears. Oirat warriors were trained in horseback riding and archery from childhood, achieving exceptional skill in these areas. Their tactics often relied on swift maneuvers, flanking maneuvers, and feigned retreats, which wore down their opponents. However, the Dzungars were not averse to innovation. Under Galdan Boshogtu Khan, they began to actively use firearms—matchlock guns (called “tsar-fire” or “buu” by them)—and even artillery. Captured Russian and Swedish soldiers, as well as craftsmen from Central Asia and China, helped to establish the production of cannons and gunpowder. The historian Iakinf (Bichurin) noted that the Dzungars “had cast iron cannons and fired cast iron cannonballs from them.” This gave them a significant advantage over the Kazakhs, who until the mid-18th century relied mainly on traditional weapons.

The army was organized according to a decimal system inherited from Genghis Khan: tens (arban), hundreds (zun), thousands (mingan), and tumens (ten thousand warriors). Each unit was headed by an experienced commander – a noyon or zaisang. Iron discipline was maintained by severe punishments for cowardice or insubordination. Before major campaigns, thorough inspections of the troops were carried out, and the condition of weapons and horses was checked. Tsevan-Rabdan probably instilled in his commanders the idea that their army was like a steel stream, and that the fate of the khanate depended on the bravery of each warrior.

The objectives of the military campaigns against the Kazakhs were multifaceted. First, it was the capture of pastures and livestock. The huge herds of Kazakh livestock were a tempting prize for the Dzungars, allowing them to solve their food problem and enrich the treasury. Second, it was to establish control over the trade routes passing through the Kazakh steppes. The Dzungars sought to impose tribute on the caravans and cities of southern Kazakhstan, such as Tashkent, Sairam, and Turkestan, which were important centers of craftsmanship and trade. Thirdly, it was to weaken the Kazakh zhuz as potential military opponents and prevent them from uniting. The Dzungar rulers skillfully played on the contradictions between the Kazakh khans and sultans, supporting some against others.

The capture of prisoners occupied a special place in the Dzungar plans. Men were often turned into slaves or forced to serve in the Dzungar army, while women and children were abducted to replenish the population of the khanate, which had suffered losses in continuous wars. Captured craftsmen—blacksmiths, gunsmiths, builders—were particularly highly valued.

The campaigns were carefully planned. Scouts (haruls) penetrated deep into Kazakh territory, gathering information about the location of nomadic camps, the number of troops, and the condition of pastures and water sources. Attacks were often carried out suddenly, at dawn, when the enemy was caught off guard. The Dzungars sought to inflict maximum damage by burning villages and driving away livestock and people in order to break the will to resist. The period known in Kazakh history as “Aqtabang Shubyrindy, Alqakol Sulama” (“Years of Great Disaster”), which began with the devastating invasion of the Dzungars in 1723 under the leadership of Tsevan-Rabdan, became an eloquent example of the effectiveness of the Dzungar military machine. Tens of thousands of Kazakhs were killed or taken captive, and many were forced to flee, abandoning their lands. From the Dzungar point of view, this was not senseless cruelty, but a necessary measure to achieve strategic goals—the complete subjugation of the Kazakh steppes. As Russian envoy Ivan Unkovsky, who was in Dzungaria at the time, wrote, Tsavan-Rabdan sought to “completely destroy the Cossack horde and bring it under his rule.”

However, despite all its successes, the Dzungarian military machine had its vulnerabilities. Its dependence on pastures made it cumbersome and limited its maneuverability in long campaigns. Losses in men and horses were significant, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to replenish them, especially in the context of a war on two fronts — against the Kazakhs in the west and the Qing Empire in the east. And although the iron fist of the Khuntaiji would continue to terrify its neighbors for a long time to come, cracks in its monolith were already beginning to appear.

Between a rock and a hard place: Dzungaria in the grip of geopolitics

The fate of the Dzungar Khanate and its aggressive policy towards the Kazakh tribes was largely determined by the complex geopolitical situation in Central Asia in the 17th-18th centuries. The Oirat rulers, trying to build their own empire, found themselves squeezed between two powerful neighbors: in the east, the Manchu Qing Empire, which had absorbed China, was gaining strength, and in the north and northwest, the Russian Empire was expanding its possessions. This game on several boards required extraordinary diplomatic skill and military cunning from the Dzungar Khuntaiji, but in the end, it was precisely this that predetermined the collapse of their state.

The wars with the Kazakhs were not just a local conflict over pastures for the Dzungars. They were part of a broader strategy of survival and domination. Weakening and subjugating the Kazakh tribes allowed the Dzungars to secure their rear and obtain resources (human and material) to counter the main threat—the Qing Empire. Emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong viewed the Dzungar Khanate as a serious obstacle to their expansion into Central Asia and as a potential center for the unification of all Mongol peoples against Manchu rule. It was no coincidence that the Qing rulers actively supported anti-Dzungar forces among the Khalkha Mongols and sought to drive a wedge between the Dzungars and the Tibetan spiritual leaders. The essence of Qing policy probably boiled down to the need to eliminate the Dzungar threat before it gained full strength.

In this regard, the Kazakh lands became strategically important for the Dzungars. Control over them not only provided economic benefits, but also created a buffer zone and a springboard for possible actions against the Qing vassals in Khalkha or even for strikes in the direction of China itself. It is not surprising that the peak of Dzungar aggression against the Kazakhs often coincided with periods of heightened Dzungar-Qing relations. When pressure from the Qing intensified, the Dzungars sought to deal with the Kazakhs as quickly as possible in order to free up forces for the eastern front.

Relations with Russia were no less complex and ambiguous for the Dzungars. On the one hand, Russia was a trading partner and potential ally against the Qing. The Dzungars were interested in purchasing Russian goods, especially firearms and metals. Russian merchants, in turn, valued the Dzungar market. There were moments when Dzungar rulers, such as Tsavan-Rabdan, tried to enlist Russia’s military support against the Qing. For example, in the 1720s, Unkovsky negotiated a possible alliance. On the other hand, the Russian advance into southern Siberia and the construction of fortresses along the Irtysh River (Omsk, Semipalatinsk, Ust-Kamenogorsk) caused serious concern among the Dzungars. These fortresses not only restricted their nomadic lands but also posed a threat to their northern borders. In addition, Russia periodically took Kazakh tribes fleeing from Dzungar raids under its protection, which also did not contribute to improving relations. The Dzungars saw this as interference in their “internal affairs” — after all, they considered the Kazakhs to be their vassals or, at least, within their sphere of influence.

Thus, the Dzungar khans constantly maneuvered, trying to use the contradictions between the Qing and Russia to their advantage. They could form temporary alliances with one side or the other, but deep down they did not trust either of them. Perhaps some far-sighted Dzungar noyon bitterly realized that both the Russians and the Chinese would ultimately pursue their own interests, which could prove disastrous for Dzungaria.

The Kazakh zhuz often found themselves as bargaining chips in this great game. The Dzungars, the Qing, and the Russians all tried to use them for their own purposes. For the Dzungars, the Kazakhs were an object of expansion and a source of resources. For the Qing, they were potential allies against the Dzungars, who could be set upon their enemy. For the Russians, they were a buffer on the southern borders and an object of gradual incorporation into the empire.

Internal strife among the Kazakh khans and sultans only exacerbated their situation and made the Dzungars’ task easier. The Oirat rulers skillfully exploited these differences, concluding separate agreements with some Kazakh leaders against others. This policy of “divide and rule” bore fruit for a long time.

However, by the middle of the 18th century, the geopolitical situation began to change to the detriment of Dzungaria. The Qing Empire, having strengthened its position, launched a decisive offensive. Russia, preoccupied with its European affairs and the development of Siberia, was not ready to provide substantial assistance to the Dzungars. The Kazakhs, driven to despair by constant raids and the threat of complete destruction, began to seek protection from Russia more actively and to take retaliatory action, such as in the famous Battle of Anrakai (although its scale and significance may have been seen differently by the Dzungars, perhaps as one of many border clashes which was not decisive for the entire war). The Dzungar Khanate, once a formidable predator, found itself in the role of a victim, caught between two imperial giants. Its aggression against the Kazakhs, which initially seemed to be a path to strengthening, ultimately only scattered its forces and brought its own end closer.

The decline of a golden dynasty: internal collapse and the final blow

Despite its formidable military machine and apparent unity, by the mid-18th century the Dzungar Khanate had been undermined from within by serious contradictions, which ultimately became one of the main reasons for its rapid decline. The centuries-long war with the Kazakhs and the exhausting confrontation with the Qing Empire required enormous amounts of energy and resources. But no less destructive were the internal strife and the struggle for power between representatives of the ruling Choros clan and other noble noyons. The death of a strong ruler often signaled a new round of internecine strife for the throne of the Khutai.

After the death of Galdan Tseren in 1745, who had managed to stabilize the khanate for a time and even inflict a number of defeats on the Qing troops, Dzungaria plunged into the abyss of civil strife. His sons and other pretenders to power began a merciless struggle, resorting to any means necessary. Tsavan-Dorji (Aja Khan), Galdan Tseren’s eldest son, was overthrown and killed by his younger brother Lama Dorji in 1750. Lama Dorji, in turn, faced opposition from other influential noyons, such as Davaci and Amursana. These internal strife fatally weakened the khanate at the most critical moment, when the Qing Empire was preparing to deliver a crushing blow.

Amursana, the Hoyt noyon, whose ancestors were closely associated with the ruling house of Choros, played a particularly sinister role in the fate of Dzungaria. In the struggle for power, he did not hesitate to seek help from the Qing emperor Qianlong, promising him vassal loyalty in exchange for support against his rivals. This was tantamount to inviting a wolf into the sheepfold. Qianlong, who had long been looking for a reason to finally resolve the “Dzungar question,” did not fail to take advantage of this opportunity. In 1755, a huge Qing army, reinforced by troops of the Khalkha Mongols and even some Kazakh militiamen eager to avenge decades of raids, invaded Dzungaria.

From the Dzungar point of view, this was treason of the highest order. Amursana, whom many Oirats considered one of their own, brought their ancestral enemy to their homeland. Divided by internal contradictions, the Dzungar army was unable to offer organized resistance. Many noyons, seeing the hopelessness of the situation or hoping to preserve their possessions, defected to the Qing side. Dawatsi, the last legitimate khuntaiji, was captured and sent to Beijing.

It would seem that Amursana’s goal had been achieved—he became the ruler of Dzungaria, albeit under the Qing protectorate. However, he miscalculated. Qianlong had no intention of preserving the Dzungar Khanate, even as a vassal state. His goal was the complete destruction of this hotbed of resistance. When Amursana, realizing his mistake, tried to raise an uprising against the Qing, it was already too late. His rebellion was ruthlessly suppressed. Amursana himself was forced to flee to Russia, where he died of smallpox in Tobolsk in 1757. Sources have not preserved his last words, but it can be assumed that he may have felt deep remorse for his actions, which led to the destruction of his people.

For ordinary Dzungars, a time of unprecedented terror began. The Qing troops, carrying out the emperor’s order to “exterminate this evil race,” pursued a policy of genocide. Men were killed, women and children were enslaved or distributed among Mongol and Turkic allies. Vast territories were depopulated. According to some estimates, out of a population of approximately 600,000 in Dzungaria, no more than 30-40,000 people survived. Many died not only at the hands of Qing soldiers, but also from hunger and epidemics that followed the destruction of their traditional way of life. Some of the Dzungars tried to make their way west to the Volga, where their fellow Kalmyks roamed, but this path was also fraught with danger. Kazakh troops took advantage of the situation to attack the fleeing Dzungars, avenging past grievances and seizing loot. From their point of view, it was a just retribution.

Thus, the once powerful Dzungar Khanate, which had terrorized all of Central Asia, ceased to exist. Its demise was caused by a combination of circumstances and internal flaws: exhausting wars on several fronts, pressure from stronger neighbors, and, importantly, internal decay of the ruling elite. The struggle for power and the personal ambitions of the noyons proved stronger than the interests of the state. In a cruel twist of fate, the Dzungars, who had long and persistently sought to subjugate the Kazakh steppes, ultimately fell victim to a more powerful imperial machine. Their centuries-long war with the Kazakhs, full of cruelty and mutual resentment, turned out to be just one act in a great tragedy that unfolded across Central Asia. The memory of this war and the Dzungar Khanate remained in the historical consciousness of the peoples of the region for a long time, serving as a warning about the fragility of earthly power and the treachery of fortune. For the Kazakhs, it was an era of severe trials, but also an era of heroic resistance that strengthened their national spirit. For the Dzungars, it was a tragedy of a people who failed to preserve their state and independence, falling victim to both external enemies and their own demons of discord. Their view of these events was that of losers, but not completely broken, whose history serves as a warning to future generations.