When Genghis Khan’s grandsons Ordu and Batu (Batu), fulfilling the will of the founder of the Mongol Empire, conquered in the 30s-40s huge territories in Eastern Europe and Western Asia, in the incredibly vast for that time Bolshomotkuda Golden Horde-Mongol Ulus there was a new inheritance: Ulus Dzhuchi, named after Genghis Khan, the father of Ordu and Batu. Its limits included Moldavia, the Northern Black Sea coast (southern regions of modern Ukraine), Crimea, the North Caucasus, steppe lands on the Don, the Volga region, the Southern Urals, Western Siberia and Kazakhstan. The Russian lands lying to the north of the Don and Volga were in vassal dependence on it. In the western part of Ulus Khan Batu began to rule, in the eastern part — in Siberia and Kazakhstan, Horde. After their death two khanates on which Ulus Dzhuchi was divided, ruled their descendants. Although Ordu was Batu’s elder brother, the supreme rulers of Ulus were the descendants of the latter, probably because Batu made more significant and heavy conquests. Ulus Dzhuchi itself was for some time part of the vast Mongol Empire, stretching from Asia Minor and Iraq to the Pacific Ocean. Its khans received a label, a permission, to rule from its supreme ruler, who sat in the Mongolian city of Karakorum. But the technical means of the time did not allow the supreme khan to control everything that happened in the remote areas of the empire, and soon the Mongol khans had to come to terms with the fact that the peripheral uluses began to separate from it. In 1266, the Dzhuchid Khan Mengu-Timur ordered his name to be stamped on coins instead of the name of the supreme Mongol ruler Khubilai, which meant the proclamation of state independence of the Dzhuchi Ulus.

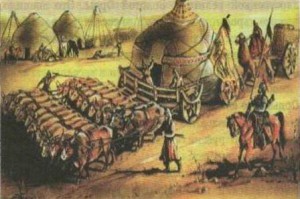

Most of the Ulus’ territories were inhabited by Turkic-speaking nomadic peoples. Its steppes have been the abode of the golden horde of nomads for centuries. By the time of their conquest by the Mongol armies here lived an ancient and once powerful ethnos of Kipchaks, whom Russian chronicles call Polovtsians. In the Volga region there was a rich Islamic state, the Volga Bulgaria, whose population also spoke the Turkic language. In the steppes of Pre-Caucasus and Lower Volga there were still unassimilized clans of Khazars — the remnants of a numerous and formidable people who created the first feudal state in the Eastern European steppes — Khazar Khaganate. After the Mongols conquered Volga Bulgaria as a state was destroyed, all Turkic peoples of these areas were forced to swear allegiance to the Dzhuchid khans, who began to establish order in the conquered lands according to their traditions. Outside the power all its Turkic population began to be called by the then international name of the Mongols — Tatars, but the Mongols who settled in the Golden Horde gradually dissolved among the more numerous local Turks and with the passage of generations forgot their original language. According to the traditions of the steppe peoples, in Ulus Dzhuchi there was equality of all subjects of the Khan, who had unlimited power over them. Therefore, national discrimination of Turks did not exist, and they quickly enough got used to life in a powerful state, felt themselves its indigenous nation, forgetting the fact that it was imposed on them by force. Nomadic cattle breeding remained the basis of the Tatar economy, and the khan himself could move across his vast steppe domain with herders driving his personal cattle from the exhausted pasture to the fat one. Of course, the khan lived not in a simple nomadic yurt, but in a high and luxurious tent, guarded by personal guards — nukers. By the name of khan’s marching tent Russians called the whole Ulus Dzhuchi Horde. In the Russian historiography it and entered as the Golden Horde. as lived in the Golden Horde, however, in Ulus actively erected and cities in which settled craftsmen, government officials, without which at that time the power could not maintain its power. The capital of Ulus-Dzhuchi became the city of Sarai-Batu («Batu’s Palace»), which existed under another name even earlier in the Lower Volga region. In the beginning of XIV century. Khan Uzbek founded on the bank of the Volga branch Akhtuba city of New Sarai, where he moved the capital of the Ulus. In Russian chronicles, the Dzhuchid capital is called simply Sarai. There was a permanent residence of khan himself. Until now, these two cities have not survived: the conquerors who invaded the Ulus Dzhuchi in the period of its decline, destroyed them. However, many cities built in Ulus and testifying to the beginning of the era of developed statehood in the «wild steppe», stand to this day: Tula, Tyumen, Azov, Astrakhan and others.

The marginal parts of the Ulus Dzhuchi were inhabited not only by nomadic Turks, but also by sedentary peoples speaking languages of other groups. As it has already been told, the majority of Russian princedoms were in dependence from Ulus. Mari, Mordva, Udmurts inhabited the northern appanages of the Dzhuchid power; in the Urals — Bashkirs, though speaking the language of the Turkic group, but never realized themselves as a single people with the Tatars. In Siberia direct subjects of khans from the descendants of Ordu were Mansi and Khanty. In the far west of Ulus’ possessions lived Moldavians, in Crimea — descendants of its ancient peoples, who later, however, adopted the language of the Kipchaks living in the Crimean steppes and consolidated with them into one ethnos, today called Crimean Tatars. In the North Caucasus within the Ulus lived peoples of the North Caucasian linguistic family (Adygs, Vainakhs, peoples of mountainous Dagestan) and Iranian-speaking Ossetians — descendants of the population of the Alanian kingdom destroyed by the Mongols.

The main trade route from Asia to Europe at that time passed through Ulus Dzhuchi: across the Volga and the Caspian coast of the Caucasus. Naturally, merchants paid duties to the khan’s treasury for the transportation of goods of great value in the European market (Indian spices, Chinese silk, various oriental fabrics and household items). Staying in the Ulus’ inns, they splurged on their maintenance and service, and the money again went to the khan. Therefore Ulus Dzhuchi was in XIII-XIV centuries one of the most powerful and rich states of the East. The rulers of very distant and not poor countries considered him. The army of Ulus repeatedly organized devastating invasions of Europe beyond the Carpathian Mountains — in the lands of the Byzantine Empire, Poland and Lithuania. These were robber invasions, the main purpose of which was to enrich the Ulus nobility, as well as to prevent the military and economic strengthening of neighbors — so that there were no competitors for influence in Eastern Europe. Also during the raids a large number of captives were captured and converted into slaves. The capture of slaves was also actively carried out during the suppression of revolts of the peoples dependent on the Ulus. Slave labor played, though not a decisive role, as in antiquity, but, nevertheless, an important role in the economy of the state. Mostly slave laborers built roads, palaces, buildings of state institutions, without which the prosperity of the country would have been impossible. how the Tatars fought

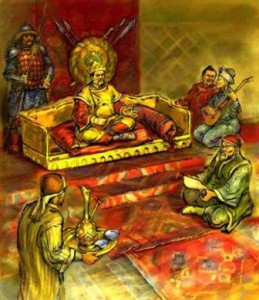

Immediately after the conquests and the foundation of the Ulus Batu Khan, according to Mongolian law, divided the conquered lands among his brothers into appanages. The rulers of the appanages were vassals of the Khan, put a certain number of soldiers in the Khan’s army, and contributed to the Khan’s treasury a part of the taxes levied from the population of the appanage. That is, the early Ulus how big was the golden hordeDzhuchi was a typical feudal steppe state. But the increase in the standard of living due to active international trade turnover required improvement of state administration, in what khans were helped by specialists invited from developed Islamic states of Central Asia. In the XIV century. Ulus Juchi was divided into four vast administrative provinces, also called ulus. Each ulus was headed by an ulusbek, a governor personally appointed by the khan. Ulusbeks in the provinces entrusted to them exercised not only civil power, but also commanded their military contingents. All the army of the Ulus Juchi was led by the highest military official — beklyaribek. In addition, he was considered the leader of all nomadic nobility of the vast country (according to feudal traditions in its hands was the mobilization of warriors), and in fact was the second after the khan person in the state. Being in charge of the army and the nobility led to the fact that sometimes beklyaribeks at their discretion removed and appointed khans. The most famous such non-kingdom ruler of Ulus was Mamai (1335 — 1380) — beklyaribek, actually unlimitedly ruling Batu Khanate on behalf of khans Abdullah and Muhammed Bulek brought by him to the throne. And in the following centuries Mamay many perceived as a real khan, but not as what he was in fact.

Non-military affairs in the state were managed by the vizir, the first minister, who headed the divan, the state council, which had executive power in its hands. The Diwan was in charge of financial and trade affairs, tax collection. To facilitate the collection of taxes, population censuses were carried out, according to the data of which the office of the diwan drew up tax lists — defters. According to the defters the tribute was collected from the peoples who were in vassal dependence on Ulus, including Russian principalities. Initially the tribute was collected by specially sent officials — baskaks, who were accompanied by military detachments ready to immediately suppress all attempts of resistance. But with the strengthening of the Ulus’ power and stabilization of the situation in the vast power, the vassal rulers themselves began to collect tribute for the khan (that is, they collected from their people the tribute for themselves and for the khan’s treasury, after which the khan’s part was sent to the Dzhuchid capital). In addition to regular tribute, there were requests — extraordinary collection of funds from subjugated peoples for extraordinary state needs (for example, in case of war).

The khan himself and beklaribek were mainly engaged in foreign policy. Ulus Dzhuchi for a long time was the most how to treat the golden horde-extensive and strong state in Eastern Europe. European kings, Popes, Byzantine emperors, and after the fall of Byzantium — Ottoman sultans sought to maintain friendly relations with the khan’s court. As it has already been told, armies of Ulus not once made plundering campaigns on neighboring countries of Europe. However, the power of Batu’s descendants had a permanent enemy. It may seem strange, but it was another splinter of the Mongol Empire — the power of the Ilkhan Hulagids — descendants of Hulagu also from Genghis Khan’s family, whose possessions covered Transcaucasia and Iran. Being strong and formidable rival powers, the Ulus Dzhuchi and the Khulagid state waged constant wars for the right to possess the resource-rich Caucasus. The devastating wars between the two powers brought a lot of misfortunes to the peoples of the Caucasus, as the opposing armies not only trampled crops, burned gardens and stole cattle, but also forced the local population to support themselves in these conditions. Like any empire, Ulus Dzhuchi also had its own «hot spots». Rebellions constantly broke out in Russia, whose people did not want to endlessly pay heavy double tax: to their princes and khan. Russian princes, in addition, often feuded among themselves, and Ulus Juchi sent troops to Russia to suppress another vassal feud, or to support a prince more favorable to the Khan. Endless rebellions rose in the Caucasus, most of the mountainous regions of which Ulus did not control at all, and the entire dependence of many mountainous peoples was expressed only in periodic robbery raids on them by Tatar troops. Well-organized, swiftly moving horse army of nomads knew no equals in the open steppe, but in mountain valleys and forests it was very vulnerable even for small detachments of the local population.

In Ulus according to still Mongol traditions there was a deep religious tolerance. The Mongols, who founded it, practiced Bonn — the shamanistic religion of Central Asia. The Kipchaks, who by the time of the Mongols’ arrival constituted the majority of the population of the steppes of Eastern Europe, were animists — they worshipped animals, primarily the wolf, who, like them, «herded the flocks». The Volga Bulgars had been practicing Islam since the VIII century. And the Khazars, who remained in the European steppes in the XIII century, were Jews (in ancient times they adopted the Jewish religion through Jewish merchants). The original ideology of unification of nomadic peoples of Ulus was the community of nomadic life. If any of the subjects of the state changed religion, it was considered his personal matter. The Russian Orthodox and Armenian churches were exempted from paying tribute, Christian temples operated in the capital of Ulus Dzhuchi, and in 1261 an Orthodox diocese was established. Only the khan himself did not have freedom of religion at first. All khans were descendants of Genghis Khan, and their kin worshipped his spirit. The change of religion meant for the khan a betrayal of the very founder of the Mongol Empire. But in 1314, Khan Uzbek broke the custom and accepted Islam. By this time, the majority of the nomadic population of Ulus were already Muslims: they adopted Islam in the process of close communication with Bulgarian theologians, officials and merchants from Central Asia. Having accepted Islam, Uzbek declared it the state religion of Ulus, that is, the life of the state was to be regulated by the norms of Islamic law. The khan’s relatives who opposed the blatant violation of Mongolian customs were executed. The adoption of Islam by the majority of the Ulus population accelerated the process of consolidation of the Tatar ethnos, as now, in addition to the traditional way of life of Turkic-speaking inhabitants of the country was united by religion, and religious community contributed to the spiritual unity of nomadic Turks and their relatives who moved to a sedentary way of life. Nevertheless, the Tatars finally realized their ethnic unity only at the beginning of the twentieth century: for example, as early as the nineteenth century, the population of Kazan and the lands around it called themselves Bulgarians, remembering who their immediate ancestors were.

The time of Uzbek Khan (reign: 1312 — 1342) and his son Janibek (1342 — 1357) was the time of the highest prosperity of the Ulus Juchi, as rich as the Golden Horde was. Luxurious palaces, mosques, caravanserais — inn and trading yards — were erected in the cities. The nobility and large officials lived in rich mansions. High city walls gave shelter to many artisans. Sarai-Batu and New Sarai, the capitals of the Ulus, were among the largest cities in the world. Uzbek maintained internal order in the state with an iron hand, demanded obedience to all laws, regardless of origin and position in society. It was he who abolished the system of tribute collection by baskaks, which was difficult for the peoples dependent on Ulus, and shifted this duty to vassal rulers (in fact, it meant the subordination of all possessions to a single feudal system of government and equalization of the legal status of all lands of the state, regardless of the nationality of their population).

However, the Ulus had a dangerous enemy, which the state could not resist. It turned out to be elementary how Tatar warriors looked like, the desire for power and wealth in the representatives of the Batu family. After the death of Janibek, various near and distant relatives of khans, who were rulers of different appanages, waged a fierce struggle for power among themselves. Everyone wanted to become one of the most powerful sovereigns of the world, to take under their control a vast, rich and strong state. Khans replaced each other with extraordinary speed, and blood was constantly spilled. The next khan who seized power had to devote all his time and energy to its retention, and the supreme rulers had no time to watch what was happening in the appanages. As a result, internal affairs in the state fell into disrepair, rulers of the appanages stopped obeying khans, dependent peoples stopped paying tribute. The defeat in 1380 of a large khan’s army from the allied forces of Russian princes — vassals of the khan, on the Kulikovo field near the Don River, which made the Golden Horde weaker, the death in battle of the eighteen-year-old khan Muhammed Bulek (a protégé of Mamay beklaribek) marked the decline of the might of the Ulus Dzhuchi. Soon the energetic Khan Tokhtamysh, who reigned in Ulus with the support of the formidable ruler of Central Asia Timur (Tamerlane), was able to restore order, suppress the separatism of appanage rulers, and make Russian princes pay tribute. However, then between him and Timur began disagreements, to which the latter, quick to reprisal, responded with a military invasion. On the river Terek the army of Ulus was defeated by Timur’s army, which did not know defeat. Then Timur went fire and sword through most of the nomadic possessions of the once terrifying to all Eastern Europe power, burned to the ground its capital of New Sarai. Tokhtamysh was overthrown by Timur Kutlug, who seized the throne and behind whose back stood beklaribek Idegei (Yedigei). Having moved to Siberia, Tokhtamysh became an independent khan in Tyumen, from where he continued his struggle for the throne of Ulus Dzhuchi. However, his attempts to regain power over the entire power were unsuccessful; the Ulus continued to fall apart.

Timur

In 1427, Khan Hadji Gerai (Girey), who seized power in Crimea, the traditional way of life of the majority of the population of which was very different from that of other Turkic-speaking peoples of the Ulus, proclaimed an independent Crimean Khanate. At the end of the 15th century it joined the Ottoman Caliphate as a vassal state and, having secured military and economic support from the latter, fought with the remnants of the united Ulus Dzhuchi for influence in the Volga region and the North Caucasus. At the same time the Crimean court concluded an alliance with the Russian princes fighting for independence, who united around the Moscow principality. In 1480 the Khan of Ulus Akhmed marched with an army to Moscow to once again force Prince Ivan III (the founder of Russia) to pay tribute. While the army of Ahmed and not inferior to it on who has defeated the gold horde and armament Russian stood on opposite banks of the river Ugra, not daring first to go on the offensive, the Crimean khan Mengli Geray has attacked the lands of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania allied to Ulus. Ahmed, realizing that his allies, busy fighting the Crimeans, would not come to the aid, retreated, which meant the withdrawal from the influence of the Dzhuchids of Russia. In 1502, the brother khans of the Ulus Dzhuchi Sheikh-Ahmed and Seid-Ahmed came out with an army against the Crimean Khanate; an Ottoman ambassador was even killed in Sheikh-Ahmed’s headquarters, demanding to stop the war with the vassal of Sultan Bayazid II. However, they failed to reach the Crimea: the Crimean army defeated them, many Ulus warriors fled to the Crimeans. In May Mengli Gerai made a devastating campaign to the lands of Ulus and burned its capital Saray. Sheikh-Ahmed fled to the city of Hadji-Tarkhan (modern Astrakhan). There were no new pretenders to the supreme throne. Rulers of large and small provinces proclaimed themselves independent khans in their lands. Ulus Dzhuchi ceased to exist, and a number of independent states emerged in its place. The largest of them were the Crimean, Kazan, Siberian, Uzbek (Kazakhstan) khanates and the Mangyt Yurt (Nogai Horde).