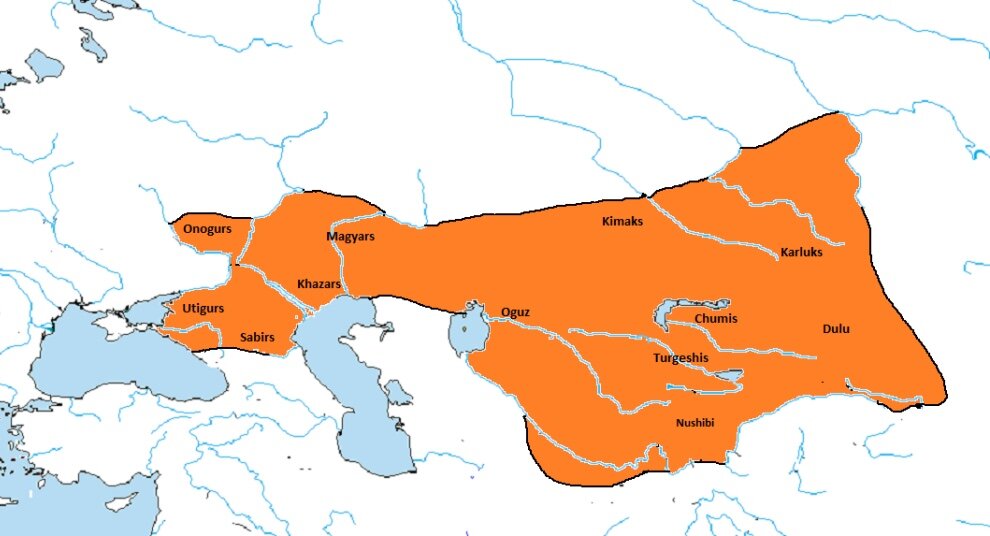

Turkic Kaganate — the first Eurasian empire of nomads

The era of the Great Migration of Peoples (II — V centuries) significantly changed the ethnic and political map of Kazakhstan, Central Asia and Eastern Europe. In the 5th century, numerous groups of the union of Turkic-speaking tribes settled in the steppe strip from Northern Mongolia to Eastern Europe, in the south their nomads reached the upper reaches of the Amu Darya.

In the V I century the lands of Kazakhstan fell under the power of a mighty power — the Turkic Kaganate, formed in the regions of Eastern Turkestan and Altai with a headquarters in the basin of the Orkhon River. The first rulers of the Turkic Kaganate were from the Ashina dynasty, a Turkic tribe. The first mention of the ethnonym is found in Chinese chronicles and refers to 542 AD. The Chinese called the Turks the descendants of the Huns. The ethnonym was originally used to name representatives of the nobility or military aristocracy, and then the ruling tribes.

The founder of the state was Bumyn (552 — 553). During the reigns of Mukan-Kagan (553 — 572) and Taspar-Kagan (572 — 581) the Turkic Khaganate achieved political domination in Central and Central Asia and extended its sphere of influence to the Black Sea region.

The aggravation of social contradictions in the Turkic Kaganate, aggravated by long-lasting jutas and famine, the attack of Sui China (581-618) on the borders of the Kaganate, and finally, the process of autonomization of its districts, which naturally began, ended in 603 with the division of the all-Turkic Kaganate into two independent ones — Eastern and Western.

The territory of the Western Turkic Kaganate (603-704) extended from the eastern slopes of Karatau to Dzungaria. The capital of the Kaganate and the winter headquarters of the Kagan was the city of Suyab in the Chu valley.

The nomadic population was organized in a (he ok bodun), quite similar to the military-administrative system that existed among the eastern Turks. Ishtemi-Kagan himself is named in one of the Chinese sources .

The first person in the state of Turks was Kagan — the supreme lord, ruler, military commander. The prerogatives of the Kagan included management of all internal and external political affairs of the state and approval of elders. He relied on the nobility from dynastic factions. The second person after Kagan was ulug. The highest titles in Kaganate — Yabgu, Shad and Elteber belonged to representatives of Kagan’s sort; they were protégés and viceroys of Kagan over vassal tribes. The judicial functions were performed by Buyuruk, tarkhan. Beks — elders and representatives of tribes, the main support of aristocratic estate on places.

The exploited mass of the Kaganate consisted of free small communal herders — . From the conquered tribes, as well as at capture of captives during military actions, the category of slaves was formed. However, the term () in the early Turks cannot be understood in the generally accepted, sense. Slave tribes were vassal tribes obliged to pay tribute to the tribe-suzerain in the form of skins, furs, etc.

Chinese chronicles report that the Turks from ancient times burned their dead along with their belongings and riding horses, after which the ashes were buried in the grave. Above the grave was placed a stone with the image of the deceased and a description of the battles in which he participated. As a result of contacts with neighboring telekas, the Turks adopted a new burial ritual — unburnt dead were buried under mounds together with the horse and equipment belonging to them.

The burial inventory of Turkic burials of the V I — V II centuries consists mainly of weapons and horse equipment, to a lesser extent — remains of clothing, jewelry and tools. Ceramics is rare. Jewelry is represented by earrings, rings, finger rings and beads. Numerous stone sculptures were found in Semirechye and Central Kazakhstan.

The military and political resources of the central power of the Western Turkic Kaganate were insufficient to keep the peoples and tribes in obedience. In the Kaganate there were continuous feuds, frequent changes of rulers, accompanied by inevitable strengthening of centrifugal forces. Sixteen-year intertribal war and dynastic feud (640-657) led to the invasion of Semirechye by the troops of the Tang Empire, whose rulers tried to rule the Western Turkic tribes, relying on their protégés from the Kagan kin.

The state of the Türgesh, Karluk, Oguzes and Kimeks

The unceasing struggle of the Turks against the Tang expansion and their proxies led to the rise of the Türgeshs and the establishment of political hegemony in Semirechye under the leadership of Uch-Elik in 704.

Being a numerous tribe, which was a part of the left wing of the Western Turkic Kaganate since the V I century, the Turgesh occupied a large territory in the Chu-Ili interfluve and controlled most of the caravan routes to Semirechye. The Turgesh influence gradually increased and the number of tribes under their control grew. Uch-Elik established on his lands 20 tutuk (appanages) with 7 thousand people in each. He moved his own headquarters, formerly located northwest of the Chu River, to Suyab and called it the Big headquarters. In the city of Kungut there was the Small rate.

In Kaganate there was a constant struggle between Kara and Sary-Turgesh, which ended with the victory of Kara-Turgesh headed by Suluk Kagan. His headquarters was in Taraz. The skillful diplomat and brilliant commander Suluk had to fight on two fronts: in the west against the Arabs, in the east against the Tang Empire.

With the death of Suluk-Kagan in 738 the struggle between Sary- and Kara-Turgesh took extremely sharp forms. The system of division of the Kaganate into Kara-Turgesh and Sary-Turgesh with stakes on Talas and in Suyab was forming. However, from the 40s of the V III c. this principle was not actually observed any more. Disunited tribes only with the help of external forces were able in 751 (Talas battle) to repel the Chinese invasion. In 756 the Kaganate fell under the onslaught of the Turkic-speaking tribe Karluks.

In Kaganate feudal relations developed, cities and trade grew. In Turgesh Kaganate along with cattle breeding agriculture developed. In connection with development of exchange there was money, monetary circulation has arisen. With penetration of Arabs Islam gradually spread.

The first information about the Karluks in written sources is contained in the Chinese chronicle of the Sui dynasty (581-618) and dates back to the middle of the 5th century. In it, the Karluks are named by the name of their main genus Bulak as inhabitants of the Altai slopes. Karluks are also mentioned in ancient Turkic runic monuments under the name . The first by time report in the Arabic-Persian literature about the Karluks is contained in Tabari (737).

The Karluks belonged to the Caucasoid anthropological type with a slight admixture of Mongoloid features.

In the V I- V II centuries the Karluks occupied the territory between the Mongol Altai and Lake Balkhash, to the south and north of Tarbagatai. The leader of the union of Karluk tribes bore the title . Social and class inequality permeated the Karluk society. The main mass of the population was made up of ordinary community members, who often fell into extra-economic dependence on the patron cattle-breeders.

In 766 all Zhetysu with two stakes of the Turgesh khagans — Taraz and Suyab — passed into the hands of the Karluk jabgu. In the V III-X centuries the territory between the Alakol Basin and the middle course of the Syr Darya was under the rule of the military-tribal aristocracy of the Karluk tribes. The Karluk confederation included various Turkic tribes: Tuhsi, Azkish, Charuks, Barskhans, Uyghurs. In the 10th century Islam began to spread among these tribes.

In the first third of the 10th century the fragmentation in the vast territory of the Karluk association intensified. The rulers of Kashgar took advantage of this. In 940 they captured Balasagun, the capital of the Karluks, and the Karluk state fell.

Few archaeological monuments of the Karluks have been discovered. Nevertheless, it is known that there were 25 towns in the Karluks’ country, a small part of which has been investigated. The Karluks’ inventory in general does not differ from similar products of other nomads. Items typical for agricultural settlements were recorded in the investigated towns.

Initially, the core of the Oguzes was formed in Semirechye, but in the process of their movement westward, it was significantly enriched by the nomadic and semi-settled population of the territory of Southern and Western Kazakhstan.

Among the Oguzes, mainly in the steppe zone of their settlement, the Mongoloid racial appearance dominated, but there were also mixed Caucasoid-Mongoloid and other types.

In the 10th century the capital of the Oguz state became Yangikent, or the so-called New Guzia. The head of the Oguz state in the IX-XI centuries was the supreme ruler, who bore the title . An important role was played by the chief leader of the Oguz army, who bore the title .

The Oguzes were divided into two exogamous fraternities: Buzuks and Uchuks, who were respectively in the right and left wings of their army. Each group included 24 tribes.

Private ownership of livestock was the basis of property inequality in Oghuz society. Along with the rich aristocracy there were masses of ordinary community members, poor people and slaves.

The main economic occupation of the Oghuz was extensive cattle breeding. There were compact groups of semi-sedentary and sedentary population. Slave trade was widespread in the steppe and sedentary-agricultural zone. Basically Oguzes were pagans, worshipped shamans. At the same time, Islam gradually penetrated into the Oghuz environment.

Archaeological materials of the Oguzes are recorded on the territory of Western Kazakhstan and on the Syr Darya, but they are extremely small in comparison with the South Russian monuments. The burials represented a small mound. In the majority of burials the inventory is practically absent.

At the turn of the 10th — 11th centuries the Oguz state began to decline. Rebellions of the Oguz tribes, dissatisfied with tax collections, became more frequent. As a result, the Oguz state fell under the blows of the Kipchak tribes. Significant groups of Oguzes under the pressure of Kipchaks passed under the rule of Karakhanids, the other part dissolved among Turkic-speaking tribes of Desht-i Kypchak.

At the turn of the VIII — IX centuries, the Kimek tribes appeared in the Priirtysh region. In the second half of the 5th — early 9th centuries, the Kimeks occupied the territory of the Western Altai, Tarbagatai and the Alakol Basin, reaching the northern limits of the Tokuz-Guz who lived in East Turkestan. Further territories from the Altai and Irtysh, to Lake Balkhash and the Dzungarian Alatau. It was at this time that the Kimak federation of seven tribes was formed. At the end of IX — beginning of X centuries their ruler began to wear the highest Turkic title — Kagan.

The headquarters of the Kagan was located in the town of Imekiya (or Kimekiya). The Kagan had real power, appointed rulers who were descendants of the tribal nobility. The governors were also military leaders who received estates from the Kagan for their service. The appanages provided the Kagan with a certain number of troops and sought to strengthen individual nomadic economies and consolidate their political weight.

In the IX — early XI centuries the Kimeks had ancient Turkic religious beliefs, among which the cult of Tengri and the cult of ancestors occupied a significant place. Shamanism was a widespread form of religion. Some groups of Kimeks practiced Manichaeism.

The Kimek monuments of the Upper and Middle Priirtysh are represented by burial mounds. The burial inventory consists mainly of armament and horse equipment, and to a lesser extent — of tools.

The Kipchak khans, torn by internal internecine strife and centralized tendencies of the Kipchak khans, who sought self-determination, as well as the migration of nomadic tribes of Central Asia, contributed to the collapse of the Kimek Kaganate in the early 11th century.

The state of the Karakhanids, Karakitai, Naimans and Kereits

In the middle of the 10th century, the Karakhanid state emerged on the territory of Semirechye, the western part of East Turkestan (Kashgar, Dzungaria and the Issyk-Kul Basin). In the formation and early history of the Karakhanid state, the greatest role was played by the tribes of the Karluk confederation, which along with the Karluk included the Chigili and Yagma.

Satuk Bogra Khan (915-955) is considered to be the ancestor of the Karakhanid dynasty. Having accepted Islam and taking advantage of the support of the Samanids, Satuk Bogra-khan subjugated Taraz and Kashgar. In 942 he overthrew the ruler in Balasagun and declared himself the supreme khagan. From that time the history of the Karakhanid state proper began.

The Karakhanid state was divided into appanages headed by their dynasty rulers, who had great rights, up to the minting of coins with their name. The appanage system gave rise to feuds accompanied by frequent change of rulers.

At the end of 30th years of XI century the state split into two parts: western khanate with the center in Bukhara and eastern khanate with the center in Balasagun. So there was a legal consolidation of the actual disintegration of the Karakhanid state into independent and semi-independent estates. At the beginning of the XIII century the Karakhanid state under the Seljuk onslaught began to disintegrate and ceased to exist. The history of the Karakhanid state came to an end.

The Karakhanid state was not a simple repetition of previous state formations. In the state, military management was separated from administrative management. The state-administrative structure was based on the hierarchical principle. The most important socio-political institution in the state was the . The term meant the institution of temporary land feudal grant with tax immunity on the terms of military service to the ruler. Khans granted their relatives and close relatives the right to receive taxes from the population of a district, region or city. The main occupation of the population was extensive nomadic and semi-nomadic cattle breeding, gradual transition to farming and accession to urban culture.

Ancient Turkic religious ideas occupied an important place in the ideology of the Karakhanids. Islam, adopted by the Kaganate as the state religion, was further spread. Islamization, especially of the southern regions of Kazakhstan, penetration of Muslim religion into the nomadic aristocratic environment led to the displacement of Old Turkic runic writing and the formation of a new Turkic writing on the Arabic script. Its representatives were famous scientists Y. Balasaguni and M. Kashgari.

Formation of Karakitai is connected with Central Asian tribes of Kidan. Kidans (Tsidan, Kita, Khita) are mentioned in written sources since IV century AD as Mongolian-speaking tribes. Their territory was located to the north of China, on the territory of Manchuria and the Ussuri region. Later, in the process of mixing with the Turkic-speaking local population, the name Karakitai was assigned to them.

During his reign, Yelui Dashi, having eliminated the Balasagun ruler from the Karakhanid dynasty, founded a state in Semirechye. After a number of successful conquest campaigns, Semirechye, southern Kazakhstan, Maverannahr and East Turkestan were included in the limits of the Karakitai state.

The head of the Karakitai had the title of gurkhan, which means . The headquarters was located in the town of Balasagun. In the country was introduced a system of yard taxation — from each house was charged one dinar. However, at the beginning of the XIII century the Karakitai state ceased to exist.

The Naiman union of tribes appeared in the middle of the century between the Upper Irtysh and Orkhon, under the name of segiz-oguz (i.e. ). Segiz-oguz occupied the lands west of Khangai to Tarbagatai.

The first information about Kereits belong to the last quarter of the XI century in connection with their adoption of Christianity. They occupied the valley of the Toly River, the area of the middle course of the Orkhon River and the basin of the Ongin River. On the eve of Genghis Khan’s invasion, the Kereits dominated the territory of all modern Mongolia and Altai, and the Mongols were also under their rule.

The growth of power of Central Asian nomadic tribes, which took place during the 12th century, led to the emergence of state formations — uluses — among the largest of them — Naimans and Kereits. The khan, the ruler of the ulus, created the apparatus of administration, first of all, the bodies of management of the khan’s staka-horde, its guard and command of troops and the druzhina. Already in the XII century the troops of ulus were divided into detachments formed by tens, hundreds, thousands. The affairs of ulus were managed by servants, who had a special title — cherbi. Office work was widespread in the khanates. Papers were written in Uigur script and sealed with the khan’s seal. Kereits and Naimans, in any case their ruling top professed Nestorian Christianity.

By the end of XII century there was a political rise of Temuchin, who, having defeated the Tatars in 1203, conquered the Kereits, and in 1206 defeated the Naimans. The defeated Naiman tribes led by Kuchluk Khan arrived in Altai, where they united with the Kereits and Merkits.

After the Mongol defeat, the Naiman and Kereite groups gradually joined many emerging Turkic peoples, in particular, the Kazakh people.

The Kipchak Khanate (early XI — 1219)

In the first half of the XI century the political hegemony in Central Asia, and then in the whole steppe zone of the Eurasian continent, including the territories of former settlement of Kimek, Kypchak and Kuman tribes passed into the hands of Kypchak khans. By the middle of the XI century, the Kipchak tribes had settled in the vast territory of modern Kazakhstan and formed their own state from Altai and Irtysh to Itil (Volga) and the Southern Urals, from Balkhash to Siberia.

The Kypchak ethnos was formed on the basis of many clans and tribes, united not on the basis of blood and kinship ties, but on the principle of territorial and economic relations. The resettlement of the Kipchaks to the west was the beginning of the formation of the whole group of present-day Turkic-speaking peoples — Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Bashkirs, Tatars and many others.

With the change in the ethno-political situation associated with the spread of the Kipchaks’ power in the Aral and Prisyrdarya regions, the name (Kipchak Steppe) appeared at the beginning of the second quarter of the XI century. The term in the XI-XIII centuries denoted the entire steppe zone of Eurasia. The territory occupied by the Kipchak tribes Russian chronicles called Polovetsian Field. The Kipchaks are also known in European sources under the names of Polovtsians, Komans, Kuns and others.

The power of the Kypchak khans was inherited from father to son. The dynasty family was considered to be the Yel-Borili, from among whom the khans came. In the khan’s headquarters, called the horde, there was the khan’s administrative apparatus, in charge of the khan’s property and the khan’s army. In military and administrative terms, the Kypchak Khanate was divided into two wings: the right wing — with a headquarters on the Ural River, and the left wing — with a residence in Sygnak (on the Syr Darya). The right wing was more powerful.

The Kypchak society was socially and class unequal. The basis of property inequality was private ownership of livestock. Nomadic cattle breeding was the main type of economy.

The Kypchak state was not united ethnically and politically. In a certain period it was fragmented and did not represent a single centralized state. By their physical appearance, the Kipchaks belonged to the transitional, so-called South Siberian race. The Kipchaks spoke a language close to modern Kazakh. The Kipchaks were not only nomadic herders, but also urban dwellers.

At the beginning of the XIII century, internal contradictions, rivalry for power, and enmity between Kipchak chiefs intensified in the Kipchak society. The once strong Kipchak Khanate fell under the blows of Genghis Khan’s troops.

Thus, in the VI — early XIII century the territory of Central Asia, including Kazakhstan, enters the orbit of a powerful ancient Turkic ethno-cultural community. The transformation of the whole socio-political system and ethno-cultural life of local inhabitants took place.