The ancient tribes of the Huns have long attracted the attention of historians. China built the Great Wall to protect itself from their raids, and the Roman Empire paid them tribute. About the mysterious nomads tell both ancient chronicles and modern research.

Huns — a mysterious and powerful people, whose history has left an indelible mark in the fate of Eurasia. Their appearance shook the world and became the beginning of a whole epoch known as the Great Migration of Peoples. But who were the Huns? Where did they come from, and what made them such a formidable force that China erected the Great Wall and the Roman Empire paid them tribute?

The Great Huns

Where did they come from?

Some researchers believe that the roots of the Huns go back to the Hun tribe, which inhabited the steppes north of China from 220 BC to II century AD Huns were famous for their incessant attempts to conquer the Chinese lands, which forced the Celestial Empire to erect a grandiose defensive structure.

By the 2nd century, however, their power had waned. Weakened by internal conflicts, the northern Huns began to migrate westward, where their path crossed with the Ugrians, who lived in the Urals and along the Volga. This alliance gave birth to a new nation, the Huns, which blended features of several tribes and cultures.

The movements of the Huns

By that time, the Huns were no longer just a nomadic tribe. They had become a powerful political entity, uniting the Sarmatians (territory of Kazakhstan), Tungus (Yakutia), Slavs, Germans and other peoples. This unique ability to assimilate was the key to their success, turning the Huns into a force to be reckoned with.

The language and origin of the Huns remains a matter of debate. Many scholars consider them to be the ancestors of the Turks or the so-called proto-Turks. English historian Peter Heather called the Huns the first Turks to invade Europe. Linguistic studies also confirm the affinity of their language with the Turkic group, which brings the Huns closer to other Central Asian peoples.

Proto-Turks, image

The appearance of the Huns further emphasized their exotic nature to Europeans. Genetic studies of the burials showed that they belonged to the Mongoloid race, had dark hair and eyes. Their features reflected a mixture of peoples: they had genetic similarities to both Central Asian and Southeastern European populations.

How were they seen?

The ancient Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, in his Acts, described the Huns as true monsters, hardly resembling humans. Their appearance inspired fear: rough facial features, massive backs of their heads, strong bodies with powerful arms and legs.

In his descriptions, they looked like two-legged beasts, like piles carved for bridges. Such representations, however, reflected Roman perceptions more than reality. University of California professor Otto Menhen-Helfen notes that such descriptions arose because of the fear and hatred that the Huns evoked. This demonization not only reinforced their intimidating image, but also served as an important weapon in psychological warfare.

The history of the Huns began in the steppes of Central Asia, where they were known as the Huns. The first mentions of them date back to the 2nd century B.C.-I century A.D., when they roamed in Transbaikalia. Clashes with China, which was protected by the Great Wall, did not weaken their pressure, but as a result of internal strife, some of the Hunnu moved westward. On the lands of Eastern Kazakhstan they formed the association Yueban, which existed until 490, until it was defeated by the Teles tribes.

By the IV century Huns occupied the Hungarian plain, spreading their influence eastward to the Volga and Terek. At its height, in the first half of the 5th century, their empire stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Caucasus, from the Urals to southern Germany. The center of power was the Roman province of Pannonia. During the reign of Attila (434-453), the Hunnish power reached the peak of its strength. It included up to 50 peoples, among which were Alans, Slavs, Ostrogoths. Its territory covered modern Germany, Czechia, Slovakia, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Southern Russia.

Interestingly, the intimidating image of the Huns, created both by their enemies and by themselves, often proved to be an effective tool. Many opponents surrendered before the battles began, preferring negotiations instead of bloodshed. Apparently, the Huns understood the power of reputation: fear of them worked for them better than any swords and arrows.

The demonization of the Huns has become an integral part of their historical legacy, but behind this intimidating facade was a people capable of adaptation, uniting disparate tribes and creating an empire that changed the face of Eurasia forever.

The Huns left a deep trace in history, but their culture and life have been studied only fragmentarily, mainly through the descriptions of medieval authors and archaeological finds. They were a warlike nomadic people whose life was inextricably linked to war.

The main occupation of the Huns was warfare. Men were constantly either participating in battles, or preparing for them, improving combat skills and making weapons. They waged continuous wars for new territories, taking cattle from the captured lands and enslaving men and women.

Life and crafts

The Huns’ craft traditions centered around the working of bone, leather, and metal. Some scholars suggest that the Huns did not always cast their own weapons, but could borrow or acquire them from neighboring peoples. The basis of their economy was nomadic cattle breeding, which required regular search for new pastures. Agriculture was poorly developed and was found only among small groups of sedentary Huns in southern Siberia and northern Mongolia, where millet was grown.

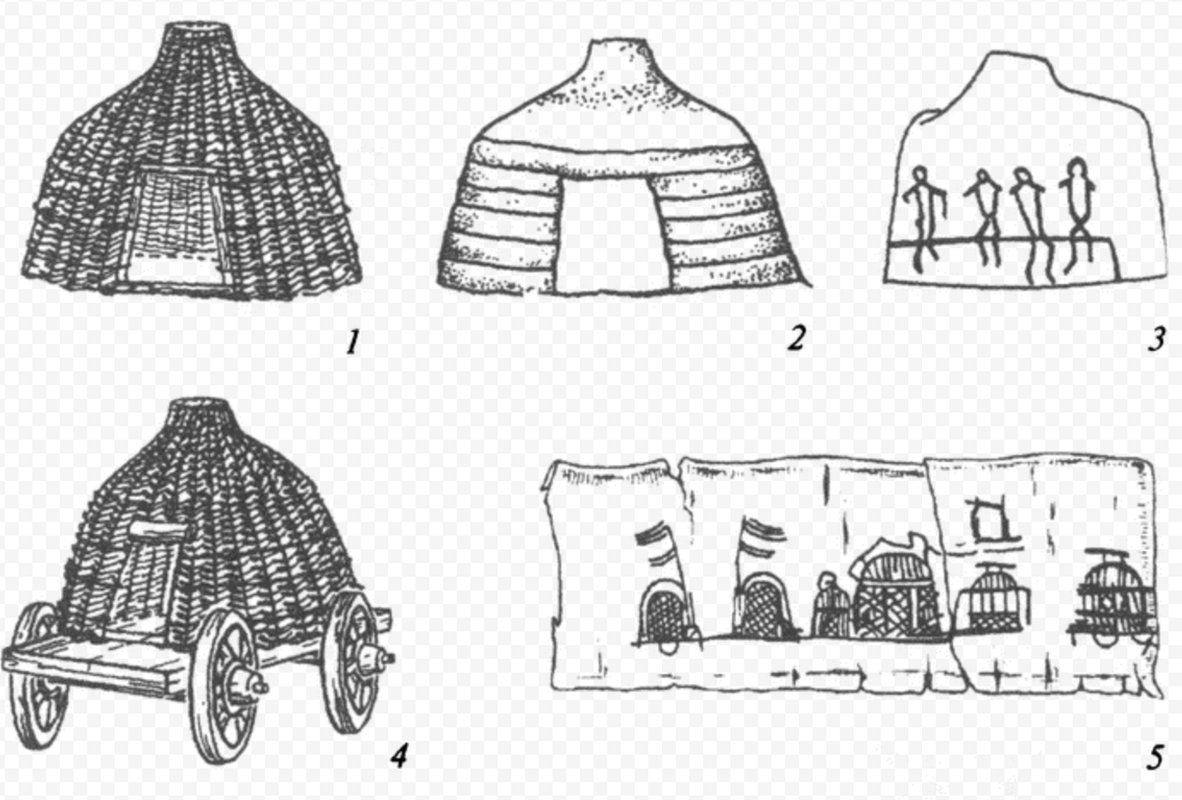

The dwellings of the Huns reflected their nomadic lifestyle. They used wagons, tents and even horses as the basic elements of their life. According to the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, they rarely entered houses and considered it unsafe to sleep under the roof. However, by the 5th century, the ambassador Priscus of Pania noted that King Attila had wooden chambers surrounded by a fence.

In cooking, the Huns used fire to cook simple food. Copper cauldrons found in Central and Eastern Europe testify to primitive but effective cooking methods. Although their quality left much to be desired, these finds show that the Huns knew the basics of cooking.

Hun dwellings

The art of war

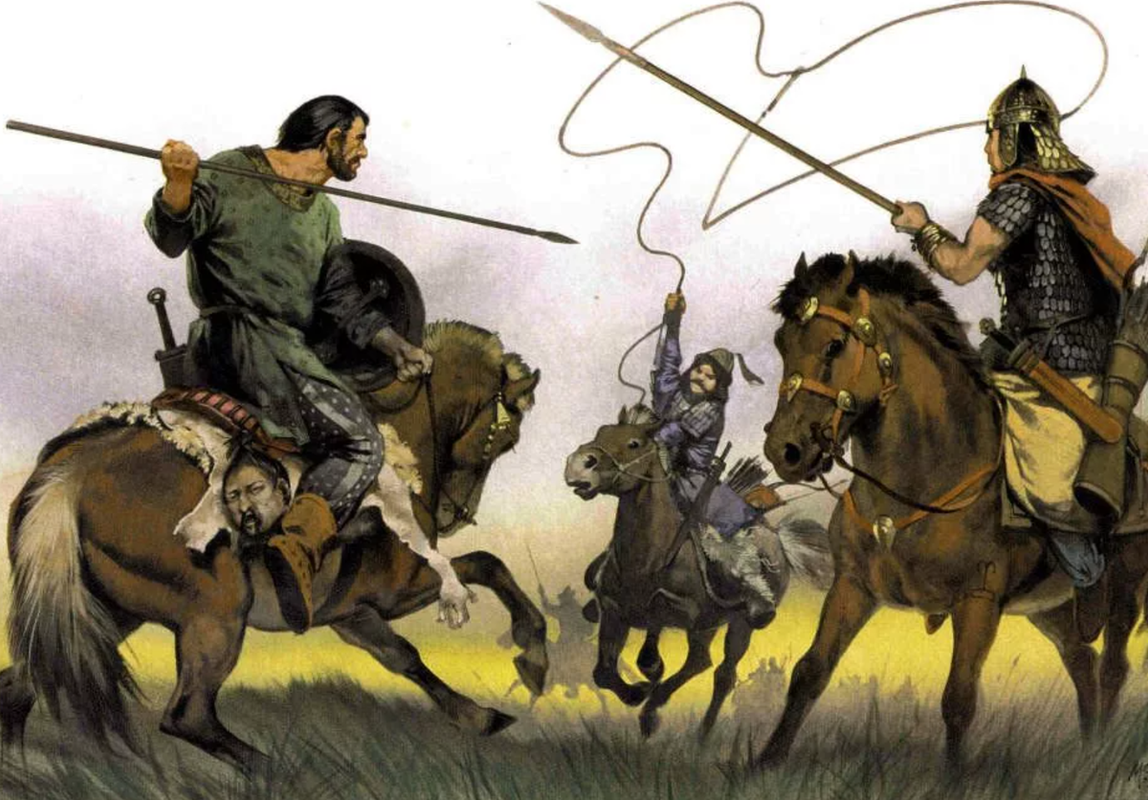

The Huns were noted for their outstanding skill in warfare. Their main weapon was the long-range bow, which the Romans considered the best in the ancient world and even adopted. In addition to the bow, they used iron swords, spears and other weapons.

The Huns’ tactics were based on surprise attacks. They attacked from different sides, raining arrows on the enemy, and when approaching, they switched to the use of swords and spears. If the attack

failed, they retreated unashamedly, trapping the enemy. Their mobility and ability to quickly disorganize the enemy army made them unbeatable in battle. Gerhard Friedrich Miller, in his History of Siberia, described the Huns as a flock of birds striving for prey, which, if unsuccessful, scattered like clouds.

Historical role

The Huns’ invasion of Europe from the east was the beginning of the Great Migration of Peoples. They defeated the Sarmatians in the 4th century, migrating after 370 CE to the south of modern Russia. This event, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, led to the assimilation or flight of the Sarmatians to the West. Under the rule of Attila (434-453), the Huns held all of Europe in fear, destroying cities and wreaking havoc.

The Huns, though terrifying to their contemporaries, had a significant impact on history. Their military prowess and unique way of life left a mark that remains a subject of interest to scholars and historians today.