One of the most notable persons in the history of the Kipchaks was Terken-khatun from the Imek tribe and the Bayaut clan

The earliest mention of the ethnonym «Kypchak» was found in an ancient Uigur inscription carved on a granite stele dated 760, discovered by Ramsted in Central Mongolia south of the Selenga River in 1909. In the literature, this epitaph has been called the Selenga Stone.

The text carved on it is part of the funerary complex of Bilge-Kagan (747-759), one of the founders of the Eastern Turkic Kaganate in the Mongolian steppes. In the fourth line on the northern side of the stele, the Uighurs have carved: «When the Kipchak Turks ruled over us for 50 years…».

The memorial complex of Bilge-Kagan is located in Saikhan somon of Bulgan aimag of Mongolia

In the Arab-Persian historiography the Kipchaks are first mentioned from 885 under the name Hifshah/hifchak/Kipchak.

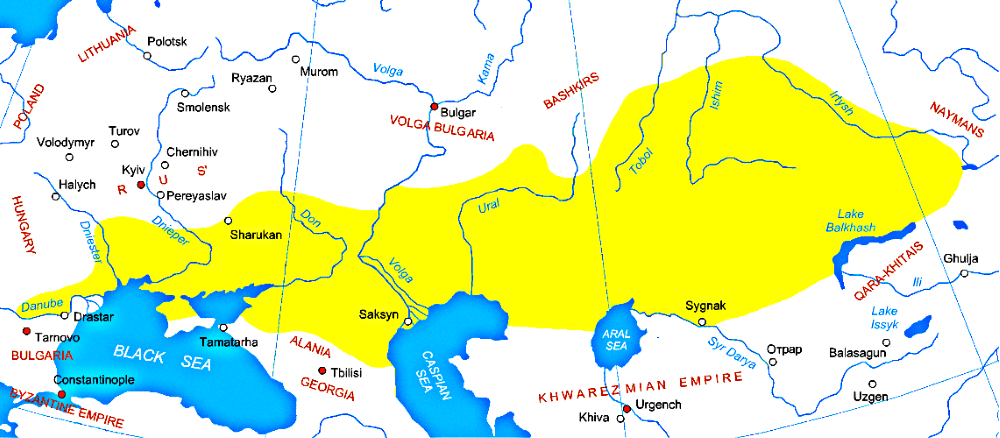

Since the 11th century, in Arab-Persian sources, the name Desht-i Kypchak (Kypchak steppe) appears instead of the name «Oguz steppe» (Mafazat al-guz), which was previously used in written sources. After the weakening of the Oguz state in the first half of the XI century, the Kipchaks gradually ousted the Oguzes from the steppes of present-day Kazakhstan, and the tribes that remained there submitted to the Kipchaks and became part of them. Having seized the Oguz lands in the basin of the middle and lower reaches of the Syr Darya, the Aral and Caspian steppes, the Kipchaks came close to the northern borders of Khorezm, which at that time was the center of a huge state.

The borders of the Kipchak Khanate in the 11th. — Beginning of the XIII century.

In 1030 Khorezmshah Altunshah wrote about the Kipchaks, who inhabited the steppes bordering Khorezm.

At the end of the XI century, the Kipchaks reached in the south the vicinity of Taraz, where they built the fortification Kanjak Sangir. The medieval Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari wrote about it [Kashgari, 1963, 3, p.444].

The eastern borders of Kipchaks in XI century were the right bank of Irtysh and slopes of Altai mountains. The left bank is marked on the map of Mahmud Kashgari as a place of habitation of the Kipchak tribe Yemeks, and the interfluve of Irtysh and Ob — of the tribe Kai or Uran, from which some Kipchak khans came [Akhinzhanov, 1973, p.59-70].

In the northeast, the Kipchaks were connected with the Sayano-Altaic hearth of civilization and culture, the carriers of which were the Kyrgyz, Khakasses and other tribes.

In the northwest, the Kipchaks came into ethno-cultural and political contact with the population of the Volga region and the Urals. The interaction of the Kipchak tribes with Bulgars and Bashkirs in the second half of the 11th — early 13th centuries developed in the direction of Kipchak linguistic and cultural influence.

The northern borders of the Kipchaks passed through the forest-steppe zone, which now separates the steppes of Kazakhstan from Western Siberia.

The following words of Mahmud al-Kashgari give an idea of the western borders of the Kipchaks: «Itil (Volga) is the name of the river in the country of the Kipchaks» [Kashgarskii, 1960, 1960, p. 3]. [Kashgari, 1960, 1, p. 103].

By the end of the XI century steppes from Irtysh to Volga were occupied by Kipchak tribes, some of their groups penetrated to Mangyshlak. On the map of Mahmud al-Kashgari on the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, the settlements of the Kipchaks are marked. They were attacked by the Sultan of the Seljuk Turks Alp Arslan during his campaign to Mangyshlak in 1065. [MITT, 1939, p.467].

By the middle of XI century Kipchaks have grasped the Black Sea steppes. In Old Russian sources this territory of settlement of Kipchaks began to be called Polovetsian Field, and Kipchaks — Polovtsians.

The lands of the eastern Kipchaks — the Volga, the Urals, the Caspian Sea, the Aral Sea, Sary-Arka and Priirtyshye were called in Perso-Arabic sources Desht-i Kipchak, a concept that spread in the 12th-14th centuries to the Black Sea steppes as well.

Composition of the Kipchak tribes

In the middle of the XI — early XII century, during the last phase of Kipchak migrations in the pre-Mongol period, five main groups of Kipchak tribes were finally formed: Altai-Siberian, Kazakh-Priural (including Volga-Ural), Podon (including pre-Caucasian), Dnieper (including Crimean), Danube (including Balkan) [Sultanov, 1992, p. 117].

Kypchak associations were natural successors of the previous state and ethno-political formations that existed on the territory from the Irtysh to the Dniester. They absorbed ethnic groups and tribes that inhabited the region in the previous centuries and became subordinate or dependent on the Kipchaks in the first half of the 11th century.

Mahmud al-Kashgari was the last known Muslim researcher to name the Kipchaks as a special ethnos in his work «Collection of Turkic Dialects» («Diwan Lugat at Turk», 1074-1078). In all other Muslim sources the term «Kypchak» became a collective name of all nomadic tribes, among which the Kypchaks themselves were completely «lost» [Yu.A. Evstigneev, 2012].

According to An-Nuwayri (1279-1332), Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), Ahmed at-Tini (1235-1318), al-Dimashqi (1301-1349) the ethnic composition of the tribes of Desht-i Kypchak was as follows: seven tribes (Borili or Ilbari, Durut/Dortoba, Toksoba, Yetoba, Burjoglu, Karabirikli, Jersan) are indicated by all the named authors, except for them, Kangarogli are indicated in the works of An-Nuwairi and Ibn Khaldun, kulabaogly, anjogly and ku-nun/kotan, and at-Tini and al-Dimashqi — imaqi, mankurogly, al-ars, buzanku, kumanku (kumanly), uz, bajna and bashkurt. What is common in the data given by the above authors is that they do not contain the ethnonym «Kypchak».

According to the above-mentioned data, one thing is clear: all nomadic tribes of Desht-i Kypchak without distinction of their ethnicity were meant under Kypchaks in the Eastern, especially Arab-Persian, sources. Ibn Khaldun, citing the list of tribes of Desht-i Kypchak, noted that not all the Kypchaks were «of one kind».

One of the ethnic components that made up the Kypchaks were the Imeks. They were a Turkic tribe and lived on the Irtysh. In the 12th century their separate groups moved to the Urals and Volga region as part of the Kipchaks. Oriental sources, Old Russian chronicles, anthropological and toponymic data speak about the presence of the Kipchaks and Imeks here. The Kipchaks also included the Turkic tribes Bayaut, Uran, and Kangli.

The close kinship of the Kipchaks and Kangli is beyond doubt, Muslim authors of the 12th — early 13th century used the names Kipchak and Kangli as synonyms. «Kangli is one of the great people from the Kypchaks», — reported Mahmud al Kashgari [Kashgari, 1963, 3, p.379].

By the XI century the Kangli tribes were nomadic to the north of the Ili River, in the area of the lower reaches of the Syr Darya and on the north-eastern coast of the Aral Sea. The main headquarters of this part of the Kangla, Karakurum, was located in the lower reaches of the Syr Darya. Kangla lived also to the east of the Urals and near Irtysh [Rashid ad-Din, 1952, I, 1, p.136-137]. Plano Carpini writes about them as the eastern neighbors of the Kipchaks, and Guillaume de Rubruk in 1253 passed the Kangla steppes in the eastern direction [Travels, 1957, p.72].

Chinese sources about the Kipchaks

The Chinese dynastic history of the XIV century «Yuan-shi» testifies that the original place from where the Qincha/Kypchaks moved to the Volga-Ural interfluve was the Jeyran valley (in Chinese Zhelyanchuan, in Mongolian Dzeren-heer) north of the river Lokha-muren in Inner Mongolia [A. Kadyrbaev, 2009].

Chinese sources also provide information of geographical and ethnographic character. «Yuan-shi» testifies that in Desht-i Kypchak «valleys and steppes are equal and wide, there are good grasses and bushes. This abundance of grasses is conducive to the breeding of horses….. By nature, the people of these places are warlike, brave and cold-blooded…».

It is also reported that the Kipchaks were good at making koumiss, a drink made from mare’s milk: «The Kipchak Banduchar served at the court of the Mongol khans. He was responsible for the herds of horses belonging to the Mongol emperor. He collected the mare’s milk and presented it to the emperor. The milk was pure and tasted wonderful. It was called the milk of the black horse …» [Yuan-shi, 1958, tsz.128].

The Kipchaks also had crafts. In «Yuan-shi» there is a mention about it: «…Kipchaks make leather …» [Ogel, 1964, S.278].

Rashid ad-Din has a number of indirect evidences, based on which we can assume the presence of a certain written tradition among the Kipchaks: «Rashid…». Having subjected to correction and criticism, careful consideration of the accuracy of the evidence in these records, collected them and put them in order … and what is not detailed in these records, let him make appropriate inquiries about it from the scholars and sages of Chinese, Indian, Uigur, Kipchak and their noble people» [Rashid al-Din [Rashid ad-Din, 1952, I, 1, p.67].

On the eve of Genghis Khan’s epoch in Desht-i Kypchak there was a process of disintegration of patrimonial and establishment of early state relations. Ancestral elders turned into clan nobility, khan clans were formed [S.M. Akhinzhanov, 1995]

As for the Kypchak statehood, V.V. Bartold writes: «The Kipchak movement is a rare example of a people occupying a vast territory without political unification and without establishing a statehood. There were separate Kipchak khans, but there was never a khan of all Kipchaks» [Bartold, T.5. M., 1968, p. 550-551].

About the relations of the Kipchaks with Kereits, Naimans and Merkits

Chinese sources contain information about the relations of the Desht-i Kypchak tribes with their eastern neighbors — the peoples of Central and East Asia. For example, with the Kereite ulus, which has already been mentioned in «Yuan-shi».

The existence of close ties between the Kangla and Kereits is confirmed by the data of a number of other Chinese sources, in which there is a more definite tradition similar to the tradition reported by Rashid al-Din and indicating genetic ties between these peoples. In support of this, there is a report that the Kangla family of Buhumu is descended from the Kereits [Ogel, 1964, s.86]. And in the information of «Menuer-shiji» even more definite text: «Kereits were the ancestors of the Kangla. The western tribes were called Kangla, eastern Kereits» [Tu Ji, 1934, s.86] [Tu Ji, 1934, tsz.20].

«Yuan-shi» provides data indicating close family ties between the nobility of Kangli and Naimans. So in the biography of naiman Chaos (Shaosy) it is written: «Shaos from naimans. His great-grandfather Taiyan (Dayan) was the ruler of the Naiman tribe. His grandfather Qiushulai (Kuchluk) … Taizu (Genghis Khan) defeated the tribe (Kuchluk)… The latter fled to the Karakitai, leaving his son… Bedein (Bede) was the son of Shaosy (Chaos). At the time when Shaosy pacified Jin, Bedein lived with his maternal grandmother, who was from the Kangla tribe…» [Yuan-shi, 1958, tsz.121]. To this we can add that earlier, in the second half of the XII century, the kinship of Naimans with Kangli was indicated by Uigur travelers. Telling about what they saw and heard on their way, they reported that the Altai is inhabited by the tribes of Nyanbaen (Naimans) and Kangli (Kangli) [Jin-shi, 1958, tsz.121].

Thus, the sources testify that in the XI-XII centuries in the Naiman and Kereit uluses a part of the population was made up of Turkic-speaking Kipchaks and Kangles.

The Kipchaks and Kangles also maintained relations with the ulus of Mongolian-speaking Merkits, whose nomads were located to the north of the Kereits ulus on the Selenga River. Rashid ad-Din pointed out that the ruler of the Merkits, named Hudu, was killed when he left the battle with the Mongols and headed for the Kipchaks. Many times the Merkits fought Genghis Khan.

Another Persian historian Juwayni also testifies that in 1218 in the country of Kipchaks and Kangla appeared the Merkits expelled by Genghis Khan from Mongolia and pursued by Mongolian troops [Rashid ad-Din, 1952, I, 1, p.124; Bretschneider, 1910, p.73].

The information of «Yuan-shi», contained in the biography of Kipchak Tutukh, confirms and complements what Rashid ad-Din and Juwayni said: «…Tai Tzu (Genghis Khan) made a campaign against the Merkits. Their ruler Hudu (Kudu) fled to the Kipchaks. Inassu (ruler of the Kipchaks) took him in. Tai Tzu (Genghis Khan) sent an ambassador to say: «Why did you hide the musk ox I wanted to shoot? Bring it back immediately. If you don’t, you will bring misfortune to yourself.» Inassu replied, «For a sparrow fleeing from a hawk, even the bushes will close so that he may stay alive. Am I worse than the grass and trees?». Tai Tzu (Genghis Khan) then ordered to march and punish him. Inassu had already grown old. There was no unity in the state of the Kipchaks. Inassu’s son named Hulusuman sent an envoy to Genghis Khan. But Syantszun (Munke-khan) had already moved troops…».

Thus, the fact of the flight of the Merkits to the Kipchaks and Kangli is one of the evidences of the links between the Kipchak tribes and the peoples who lived to the east of them.

The Kangli also maintained relations with the Jin empire of the Jurchens, which occupied the territory of modern Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, as well as Northern China. In Chinese sources, for example, the Kangli under the name of Kangli are mentioned in the XII century (1161-1189) in connection with the embassy of Kangli and Naimans to the court of the Jin emperor [Jinshi, 1958, tsz.121, p.1100].

On the relations between the Kipchaks and the Karakhanids

In 1065, the Seljuk ruler Alp Arslan made a campaign to Mangyshlak against the Kipchaks. The Seljuk sultan, having obtained from the Kipchaks an expression of submission, made a campaign to Jend and Sauran. As a result of this military campaign, part of the Kipchak tribes temporarily became dependent on the Seljuks of Khorasan.

At the end of the last quarter of the 11th century, the Kipchaks still ruled in Mangyshlak and the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea, and some groups of Oghuz and Turkmen tribes were politically dependent on them. In 1096, the Kipchak tribes made a campaign against Khorezm. However, the Seljukids, the patrons of the Khorezm Shahs, forced them to return to Mangyshlak.

According to Mahmud Kashgari, the Kipchaks were in complex political relations with the rulers of the Karakhanid dynasty. The Karakhanids made campaigns to the eastern limits of the Kypchak ulus, while the Kimeks from the banks of the Irtysh raided the limits of the Turkic Muslim power in Semirechye.

At the end of XI — beginning of XII cc. Dzend, Yangikent and other cities of the lower Syr Darya were under the rule of Kipchak chiefs. However, in the first half of the 12th century, they became the scene of a persistent struggle between the Kypchak khans and Muslim dynasties of Central Asia, who tried to seize it at any cost. Under the banner of spreading Islam, Khorezmshah Atsyz conquered Jend, and then advanced northward, adding Mangyshlak to his possessions.

In 1133, the Kipchaks were defeated by Atsyz, who undertook a campaign from Dzend to the interior of Desht-i Kypchak. The sources do not contain any additional information about the causes of the first major defeat. In fact, from this time (the second third of the 12th century) began the fragmentation of the Kypchak Khanate, caused by a number of reasons, the main of which were: the formation of pro-Khorezmian orientation among the nobility of the Kypchak tribes, the intensification of internecine struggle for power.

From the second half of the XII century, especially from the reign of Tekesh (1172-1200), a purposeful policy of rapprochement with the Kipchak nobility was pursued. The leaders of the Kipchak tribal groups, Kangla, Imeks and Uran were attracted to the service of Khorezm Shahs. The ruling nobility of the Kypchak Khanate and the Khorezmshah dynasty entered into kinship ties with each other. The Kypchak Khan Dzhankeshi married his daughter Terken-Khatun to Khorezmshah Tekesh. According to medieval traditions, property relations as a «union of peace and kinship» at different levels of interethnic ties were extremely important. They entailed a whole system of real and often close ties, manifested in social and political mutual support.

However, in general, the political situation in the region was characterized by extreme instability, which was caused and supported by the Khorezmshahs as a result of their policy aimed at undermining the foundations of the independent Kypchak ulus. For this purpose, they created a closed military estate from the representatives of the Kypchak aristocracy, which supported the aspirations of the Khorezmshahs. The ideological basis of this line was the Islamization of the Kipchaks, first of all their nobility. Meanwhile, significant groups of Kipchak tribes remained outside Islam until the end of the 12th century. The area between Jend and Farab was considered to be the area of pagan Kipchaks until the end of the 12th century.

According to the established tradition, the rulers of Khorezm took wives from the khan clans of Kangli and Kypchaks. The association of the Kangli tribe in the 2nd half of the 12th — early 13th centuries represented a large political force, striving for self-determination, thus not contributing to the political unity of the Kypchak Khanate. As is known, the main military support of the Khorezmshahs was made up of groups of Kangli and Kypchaks. In the beginning of the XIII century, an important role at the court of Khorezmshahs was played by the leader of Kangla Amin Malik, whose daughter was married to Khorezmshah Ala ad-din Muhammad. The Kipchak aristocracy, endowed by Khorezmshahs with state and military posts, defended the interests of the latter. Internal contradictions in the Kipchak society intensified, caused by the pro-Khorezmian orientation of significant groups of Kipchaks, as well as rivalry for supreme power. In this environment, the Khorezmshahs skillfully incited and supported enmity between the Kipchak chiefs.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the state of Khorezm Shah Mohammed (1200-1220), who claimed primacy in all Muslim Asia, included the Sygnak region. Despite the loss of the Sygnak domain, the Kipchak khans continued to wage a stubborn struggle with Khorezm. From Jend Muhammed undertook repeated campaigns to the north against Desht-i Kypchak. In 1216, during one of the military campaigns against Kadyr Khan, he reached the Irgiz, where in the Turgai steppes he accidentally encountered Genghis Khan’s army pursuing the Merkits who had fled to the country of the Kipchaks. After the battle with the Sultan, the Mongols retreated under cover of night. It was the first appearance of Mongols on the territory of Kazakhstan, which suspended the long rivalry between the Kipchaks and Khorezmshahs. The era of Mongol conquests came.

Conclusion

Thus, as testified by multilingual sources, first of all Chinese dynastic histories, the Kipchaks appeared in the 11th century in the vast expanses of modern Kazakhstan, the Urals and the Volga region, having migrated from Inner Mongolia, their ancestral homeland, and by the end of this century had settled in the North Caucasian and Black Sea steppes up to the Carpathians. Many Kipchaks and Kangli were in Khorezm. They also remained in their ancestral homeland. This period is the time of consolidation of the Kipchak and Kangla tribes into relatively stable nomadic associations of the state type on the territory of the Eurasian steppes from the Altai to the Danube, known in the XI-XIV centuries. The traces of their existence have been preserved in the ethnic memory of the territorial successors of these medieval Turkic tribes — modern Turkic steppe peoples — Nogai, Kazakhs, Bashkirs, Crimean Tatars, in whose tribal structures the Kipchak and Kangla clans are represented. Ethno-cultural continuity can also be traced in linguistic terms, since the languages of the above-mentioned steppe peoples, as well as the Volga and Siberian Tatars, belong to the Kypchak group of Turkic languages.