The XIII century in world history was marked by a unique event — the formation of the Mongol Empire. As V. V. Bartold (1869-1930) noted, never before or after the unification of the countries of the Far East and Eastern Europe, West and Central Asia under the rule of one dynasty. Of all the state formations into which the Mongol Empire disintegrated, the Golden Horde was of particular importance for the political and ethnic history of the Turks.

Nevertheless, there is not a single special work on the history of the Golden Horde in the Oriental literature. But it is the Muslim sources, along with Russian chronicles and notes of European travelers and missionaries, have preserved the most detailed information about the state of Genghisids in the Eurasian steppe with the center in the Lower Volga region, about the Golden Horde — the object of our study.

Kipchak is the largest tribal union of Turks. For the first time in Muslim sources the Kipchaks are mentioned by the Arab author, Iranian by origin, Ibn Khordadbeh, who in 232 AH/846-847 wrote «The Book of Ways and Provinces».

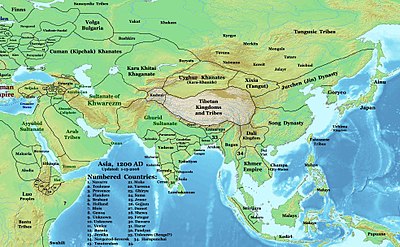

Judging by the sources, in the VIII-X centuries, the Kipchaks lived in the Altai, in Priirtysh, and then in the steppes of modern Central Kazakhstan and in the Aral Sea region. By the middle of the XI century, the heritage of the Oghuz on the right bank of the Syr Darya and in the Aral Sea region, as well as the heritage of the Pechenegs in Southern Russia had passed to the Kipchaks.

Thus, in the XI century in the west the Kipchaks came into contact with Russians and Western Europeans, although neither of them knew the word Kipchak. Russians called Kipchaks Polovtsians, and their country — the Polovtsian Field, Western Europeans — Komans, and the country — Comania, or Great Comania.

The importance of the Kipchaks in the steppe was so great that Muslim authors from the 11th century began to call the entire vast area from the Irtysh in the east to the Dniester in the west in Persian Desht-i Kipchak (Kipchak Steppe, Kipchak Steppe), or simply Kipchak.

It should be noted that this vast region inhabited by the Kipchaks remained at that time outside the Muslim world — the Kipchaks were mostly pagans.

Desht-i Kipchak was divided into two parts: Western and Eastern Desht-i Kipchak. Western Kipchak stretched from east to west from the Yaik (from the XVIII century the Ural River) to the Dniester, and from south to north — from the Black and Caspian Seas to Ukek (the remains of this city are in the vicinity of modern Saratov).

The western border of Eastern Kipchak was the Yaik, the eastern border — the Irtysh, in the north — the areas of the middle and lower reaches of the Tobol, in the south — Lake Balkhash and areas adjacent to the east to the middle and lower reaches of the Syr Darya. In the XII century, the capital of the non-Muslim Kipchak possession of Eastern Desht-i Kipchak was the city of Sygnak, located on the right bank of the middle reaches of the Syr Darya.

It has already been established in science that individual khans ruled in Desht-i Kipchak, but there was never a khan of all Kipchaks. Kipchak nomadic principalities existed until the beginning of XIII century. Their fall was caused by a new movement of peoples associated with the rise of Genghis Khan and the formation of the Mongol Empire.

At the beginning of the XIII century in Eastern Desht-i Kipchak one of the Kipchak sovereigns was Kunjak. According to Rashid ad-Din (died in 1318), when Eastern Desht-i Kipchak was conquered by Mongols, Kunjek, together with his son named Kumur-bish-Kunji, a skillful hunter, was captured and was in the service of Genghis Khan as an elder of umbrella-holders (a special kind of umbrella held over the sovereign was one of the important signs of monarchic dignity in the East). About the further destiny of the last sovereign of the Eastern Kipchaks nothing more is known.

According to Russian annals of XII — beginning of XIII century dozens of names of Cuman princes of the Western Desht-i Kipchak are known. But only two leaders of the Western Kipchaks — Bach-man and Kotan — are mentioned in the battles with the Mongols. The end of both was tragic.

Well-armed and equipped army of Mongols headed by tsarevich Batu (Batu), grandson of Genghis Khan, in the fall of 1236 began the conquest of Volga Bulgaria and by the spring of 1237 conquered it. Then the army of Mongols was divided into several corps, and each was defined its own direction. Part of the army moved into the expanses of Western Desht-i Kipchak to war with the Kipchaks and the peoples of the North Caucasus.

The Western Kipchaks offered desperate resistance to the Mongols. Both Muslim and Chinese sources contain a story about the Kipchak leader Bachman.

I will cite a passage from the Chinese work «Yuan shiu> (1370) in the translation of the largest Russian orientalist, Professor E. I. Kychanov about the capture of Bachman.

In his young years, the tsarevich Munke, son of Tului, son of Genghis Khan, «often attacked the Kipchaks. Their ruler Bachiman fled to an island in the sea. Munke learned about it, just when the Mongol troops reached their (Kipchaks) lands, a great wind arose and drove the sea water. It became so shallow that it was possible to cross to the island where Bachiman was hiding. Munke said joyfully: «It is Heaven that has opened the way for me!» Then moved forward and destroyed their (the Kipchaks) army. Took Bachiman captive and ordered him to kneel down.

Bachiman said:

«I am the sovereign of the state. Can I ask to preserve my life! At the same time, I myself have not defected to the enemy’s side, how can I, kneeling down, remain a human being?»

Then they ordered him to be imprisoned».

Muslim sources contain more detailed information about Bachman. According to these eastern sources, Bachman appears as a fearless shirtmaker and a successful warlord.

When in the spring (or summer) of 1237 the Kipchaks were defeated by the Mongols on the shore of the Caspian Sea, Bachman escaped the sword and rallied around himself a detachment of «Kipchak brave men». Bachman acted skillfully and surely. Persian statesman and historian Ju-veini (born in 1225, in 1260 finished his famous work «Tarikh-i Jahan-gushai» — «History of the conqueror of the world») about Bachman writes so:

«Little by little the evil from him increased, confusion and disorder multiplied. Wherever the Mongol troops were looking for traces of him, they did not find him anywhere, because he went to another place and remained unharmed».

According to Rashid ad-Din’s «Collection of Chronicles», the main source on the history of the Mongol Empire, the Mongols learned that Bachman with his detachment was hiding somewhere in the forests on the bank of the Itil (Volga), and moved against him two hundred ships, each of which had one hundred soldiers, and two detachments went on a raid on both banks of the Volga. In one of the Itil forests they found traces of the camp that had left in the morning: broken wagons, fresh dung and so on. A sick old woman was also there. From her they learned that Bachmann had moved to one of the islands in the middle of the river.

Immediately an order was given to the troops to go by boat to that island and capture Bachman. Before Bachman realized what had happened, a detachment of Mongols attacked him. The captured Bachman was brought to the Mongol king Munk (Meng in Turkic), who ordered his brother Buchek to cut the prisoner into two pieces.

Another leader of the Western Kipchaks, Kotan, also resisted the Mongols for a long time. However, the forces were unequal, and he found it expedient to appeal to the Hungarian king Béla IV with a request for asylum. His letter also indicated the willingness of the Kipchaks to accept Catholicism.

Wishing to create a Hungarian-Kipchak military alliance, the king respected this request and in the fall of 1239 personally solemnly met Kotan and his forty-thousand horde on the border and instructed high officials to settle the nomadic Kipchaks on the territory of Hungary.

However, Béla IV’s intention to use the Kipchaks to fight the Mongols did not materialize. In the year of the Mongol invasion of Hungary (1241), Khan Kotan and his close entourage fell victim to a conspiracy of Hungarian feudal lords, and the Kipchak warriors with their families and livestock went to the Balkans.

Thus, as a result of the Mongol invasion, the old Kipchak aristocracy was barbarously destroyed. The future of the Kipchak herders was different: someone died, someone fled, and someone was captured and sold into slavery. But in their mass Kipchaks remained nomadic in their steppes and in the XV century formed the core of Kazakhs, in different proportions joined many other new Turkic nationalities formed after the collapse of the Golden Horde