Since ancient times, warlike Turkic tribes have led a nomadic way of life and engaged in cattle breeding on the vast steppe expanses from the mouth of the Danube to the Altai. Just as it was in VI — VII centuries at Bedouins of Arabian Peninsula, since the second half of X century at Turkic nomads began the process of decomposition of tribal system and military-feudal nobility began to stand out, dreaming about expansion of the possessions. At about the same time Turkic nomads accepted Islam and thus received motivation for new conquests. Associations of Turkic tribes living in the steppe regions of Central Asia began to form. One of such tribal associations, headed by the Karakhanid dynasty, took advantage of the decline of the Samanid state and in 992 seized Bukhara and the adjacent regions of Central Asia.

In the middle of the X century, another association of Turkic tribes, called Oghuz, appeared north of the Caspian and Aral seas in North-Western Iran. It was headed by the Seljuk family. Subsequently, the name of the dynasty — Seljuk or Seljukids — spread to all the tribes united by it. The Seljuk tribes began to infiltrate areas of the Islamic world, primarily Khorezm and Maverannahr. The main goal of the Seljuk nobility was to extend their power over the sedentary agricultural population of neighboring regions.

Iranian Samanid rulers indirectly contributed to the expansion of Turkic tribes. As early as in the middle of the 10th century, Alp-Tegin, the commander of the Samanid army in Khorasan, who headed the court Turkic guard of gulams, played a prominent role at the Samanid court. The growth of his influence under weakening rulers and his attempts to interfere in court intrigues caused Alp-Tegin’s disgrace, and he was forced to leave with his gulams to Ghazna (Eastern Afghanistan), where he founded an independent principality.

Alp-Tegin ruled in Ghazna for a decade and a half, after which another Ghulam leader, Sebyuk-Tegi, came to power. Formally remaining the viceroy of the Samanids, Sebyuk-Tegin, like his predecessor, was in fact the full master of his domains and is considered the founder of the Ghaznavid dynasty. The rise of this dynasty and its entry into the world arena is associated with the name of Sebyuk-Tegin’s son, the famous Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi. Taking advantage of the fact that the Samanid state, which was in a state of political instability, was struck by the Karakhanids, Mahmud Ghaznevi seized the Samanid lands to the south and west of the Amu Darya. In 1017 he conquered Khorasan, and in 1029 he conquered the Iranian possessions of the Buwayhids: Rey, Qazvin, Hamadan, and Isfahan. In the north he established a border with the possessions of his Karakhanid rivals along the Amu Darya and seized Khorezm. By the time of his death, Mahmud’s empire was a vast state equal in power to the Abbasid Caliphate at its height. However, the state of Mahmud Ghaznavi became powerful mainly due to the personality of the sultan himself, and under his son Masud the empire began to decline, and soon the Seljuk Turks, taking advantage of this, dealt the Ghaznavids a crushing blow.

The Seljuqids were led by two of Seljuk’s grandsons, Chagri-bek and Togril-bek. In 1038 the Seljuqids seized Northern Khorasan, and Chagri-bek was proclaimed sultan in Merv, and Togril-bek (1038-1063) in Nishapur. Masud tried to resist the Seljuqids, but in 1040 his army was defeated at Merv. The Ghaznavids lost Khorasan, and over the next decade (1040 — 1050) all of Iran fell into Seljukid hands.

Now it was Iraq’s turn. Proclaiming himself the defender of Sunnism and the enemy of the Shiite Buwayhids, who usurped power in the Caliphate, Togril-bek I moved on Baghdad. In 1055 he easily expelled a small Buwayhid garrison from the city and forced the powerless caliph al-Qaim (1031-1075) to declare him «sultan and king of the East and West», as a sign of which he put a two-horned crown on him and belted him with two swords. To Khalifa Togril-bek I, as before the Buwayhids, left only a phantom spiritual authority. Thus was born the empire of the Great Seljuks.

The zealous Sunni Seljuqids rendered to the Caliph all the proper signs of external deference. Togril-bek I personally arrived in Baghdad to receive investiture, prostrated himself and kissed the ground before the Caliph al-Qaim, but at the same time the full power in the state concentrated in his hands. In 1059 the former Buwayhid warlord Arslan al-Basasiri made an attempt to return the power in Baghdad to the old dynasty, for which he even tried to enlist the support of the Fatimids. But Togril-bek I acted decisively. He arrived with an army in Baghdad, defeated the detachment of al-Basasiri, executed him and restored Seljukid power.

The Seljukid conquests continued under Alp Arslan, the second sultan of the Seljukid state (1063-1072), the nephew of Togril Bey I and son of Chagri Bey. Under him, the state included the whole of Iran, Iraq and Transcaucasia (Armenia, Azerbaijan and Eastern Georgia), as well as a significant part of Asia Minor. From 1064, the first Turkic groups began to penetrate into Syria. Initially they acted as allies or auxiliary troops of rival local Bedouin emirs. In 1071, the Fatimid commander Badr al-Jamali, then ruler of Acra, invited one of the Turkic leaders, a certain Atsyz, to prevent raids on his possessions in Syria by rampaging Bedouin tribes. However, Atsyz decided to act in his own interests and seized the whole of Palestine with Jerusalem. And when the Fatimids, who were concerned about his claims, attempted to take away his captured lands, Alp Arslan, who wanted to prevent the Fatimid penetration into Syria, declared a «holy war» to the Shiite-Ismaili dynasty of the Fatimids and in turn invaded the country with an army. He took Aleppo without much difficulty, but had to halt further advance and move his army to the northeast in order to avert a threat to his rear from the Byzantine emperor Romanus Diogenes. With the departure of Alp-Arslan’s army, Atsyz continued his conquests in Syria. In 1076 he took possession of Damascus, and in the following year he made an attempt to invade Egypt, but was repulsed by Badr al-Jamali. Fearing the advance of the Fatimid army, Atsyz appealed for help to the new Sultan of the Great Seljuks, the son of Alp-Arslan — Malik-Shah (1072 -1092). Malik-Shah willingly responded to the call and sent a large detachment led by his brother Tutush to help Atsyz, authorizing him to become emir of the lands that he was able to capture. As a result, almost all of Syria, ruled by Tutush from Damascus, fell into Seljuk hands, and only a narrow coastal strip with Akra and Tyre remained under Fatimid control. In 1095 Tutush died in the struggle for the post of the head of the Seljuk sultanate, and his possessions were divided by the Turkic emirs.

On the territory of Byzantium Turks began to penetrate under Mahmud Ghaznavi. Alp-Arslan has decided to support movement of Turks-Oguz to the West. Leaving Syria, he quickly regrouped his detachments and directed them to the Byzantine border. In 1071 there was a grand battle at Manzikert. Roman Diogenes’ army was defeated, and the Byzantine emperor himself was taken prisoner.

As a result, the Byzantine border fortifications were broken through, and the Turks rushed in a continuous stream into Asia Minor, settling Anatolia and turning the vast captured areas into pastures.

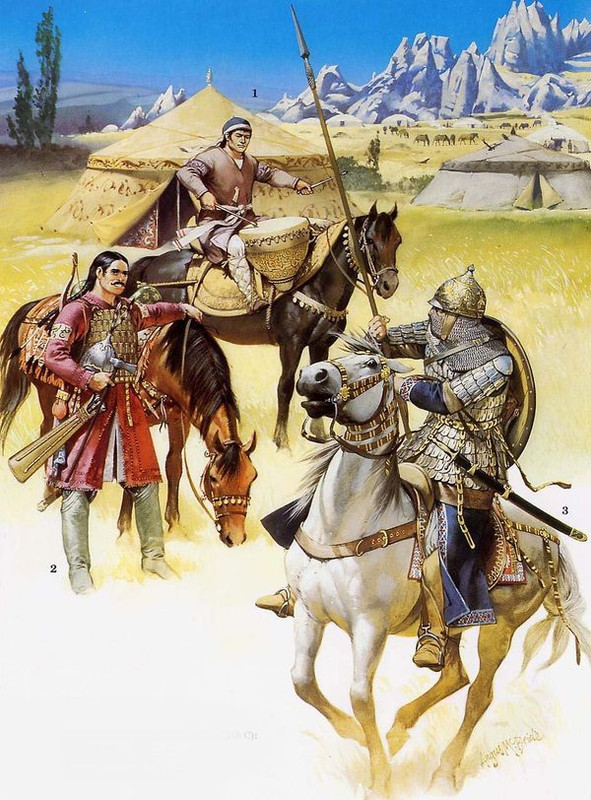

The Seljuk conquests were carried out by Turkic tribes, which at the time of the dynasty’s rise to power were its main support and dreamed only of expanding the areas of nomadic agriculture. This created difficulties for the emerging empire, whose economic position depended on the prosperity of settled agriculture, and in the cities — crafts and trade. Therefore, as the power of the Seljuqid dynasty consolidated, they began to view the nomads as a serious threat to the stability of the state they were creating. Taking this into account, Alp-Arslan, under the pretext of the need to protect the borders, ordered the resettlement of most of the nomads who ensured the dynasty’s accession to power to the peripheral regions. By this act he as if finally broke with the traditions of the conquering Turks and turned the state formation into a powerful empire.

The victory of the Seljuks at Manzikert opened the way for Turkization of Asia Minor. One of the emirs, Sulaiman (1077-1086), seized leadership among the Turks who invaded Anatolia. As a result, an actually independent Seljuk state of Ruma was formed in Anatolia, i.e. the area that was once part of the Roman Empire. Like the head of the Great Seljuk State, Sulaiman also gave himself the title «Sultan». At first he established his capital in Iznik (Byzantine Nicea), away from the Great Seljuks’ possessions in the east, and after losing the city in the war with Byzantium, he moved the capital to Konya. Thus, in addition to the Great Seljuk Sultanate, another Turkic state was formed in Anatolia.

The Seljuqids of Rum never set out to crush Byzantium. Their political ideal was to preserve dualism in Anatolia, and they clearly distinguished between Islamic domains (Dar al-Islam) and Christian lands (Dar al-Harb), which were to remain under the Byzantine emperor. They considered the Great Seljuk sultans to be their main opponent. Therefore, when the conquests of the Seljuks met with opposition from the energetic Byzantine Emperor Alexius Komninus (1081 -1118), who managed to return to Byzantium most of the lost possessions in Western Anatolia, Sulaiman willingly concluded a peace agreement with the emperor, turned his gaze to the east and tried to take the northern part of Syria between Antioch and Aleppo from the Great Seljuks. War broke out between the two related Turkic states. In 1086, Sulaiman was defeated by the Seljuk warlord Tutush and was killed. However, the Seljuk state of Ruma existed after that for another 120 years, until it was finally destroyed by the Mongols. Under Togril-Bek I, his nephew Alp-Arslan and especially under Alp-Arslan’s son Malik-Shah, the Seljuk state reached its highest political power. The possessions of the Great Seljuks included a vast territory from the Amu Darya River and the borders of India in the east to Northern Syria in the west. Malik-Shah made Isfahan his capital. He kept here a lavish court befitting the ruler of a great state, established a strict ceremonial and introduced court posts. The Seljuk upper class quickly adopted the lifestyle of the educated part of the Arab-Iranian society under its domination. This cultural assimilation found its expression in the very name of the third Seljuk sultan. Unlike his two predecessors, he did not wish to bear a Turkic name, but adopted the name «Malik-Shah,» a combination of the Arabic word «Malik» and the Iranian «Shah» for «king.»

Needing experienced officials, the Seljuk conquerors, just as their predecessors the Arab conquerors had done in the past, recruited educated men from the Iranian intelligentsia to the civil service. The most prominent figure among the official nobility was the famous wazir of the sultans Alp Arslan and Malik Shah, Abu Ali al-Hasan al-Tusi, known as Nizam al-Mulk (died 1092). Nizam al-Mulk strove to create a centralized state, the model of which he considered the Abbasid, Samanid and Ghaznavid states in their heyday. He expressed his political views in his work «The Book of Governance» («Siyaset-name»), where he recommended sultans to have a large army suitable for suppressing rebellions of unruly emirs in the provinces and feudal turmoil. He was particularly hostile to the Shi’ite Ismailis and the Fatimid state that opposed the Seljuks.

Such rapid successes of the Seljuqids in conquests were to some extent connected with their consistent support of Sunnism. They favored the Sunni clergy and dervish sheikhs in every possible way. To strengthen the traditional Islamic ideology, Nizam al-Mulk created a special educational institution — madrasa, named after its founder «Nizamiya», which trained theologians capable of defending the Sunni doctrine. Later, similar educational institutions were established in other areas of the Islamic world on the model of Nizamiyah.

Initially, the Seljuqids viewed their empire as the property of a single family rather than of individual members of the family. In practice, over time, the Seljuk regime acquired an increasingly monarchical-absolutist character, and the head of the entire Turkic clan turned into a single-powered sultan, adopting despotic methods of governance from the Abbasid caliphs. Formally considering themselves as Abbasid military commanders, Seljukid sultans seized the power to which all Turkic conquerors had to obey unconditionally. During the period of Seljuk conquests, such one-man rule was motivated and justified by the common purpose of all the participants in the campaigns. But as the power of the Great Seljuks strengthened, centrifugal tendencies in the state began to increase. A contradiction arose between the desire for centralization of governance on the part of the Sultan and the original Seljuk tradition of ruling the state by the whole clan, rather than through one strong ruler. Each member of the growing Seljuk dynasty considered himself entitled to have his own inheritance in the common state, which would only partially extend the power of the sultan. From the end of the XI century Seljuk nobility was no longer interested in a strong central authority and began to show separatist tendencies.

The last decades of the 11th century saw an increasing weakening of the authority of the central government in the Great Seljuk state. Members of the dynasty who were not subject to any discipline and the emir commanders who ruled in various regions of the empire were falling out of obedience to the sultan. Although Nizam al-Mulk made every effort to keep the administration in his hands, sometimes acting even against the will of the Sultan himself, whose guardian and tutor he had been in the past, his efforts were often insufficient to preserve the unity of the state. All his attempts to replace the federation of members with a kind of centralized absolutism on the model of the Sasanian model failed because of the weakness of the central administration and the lack of material resources. The economically powerful areas of the Islamic world (Central Asia and Egypt) were outside Seljuk power, and the central areas of the state (Iraq and Syria) suffered great economic hardship.

The weakening of Seljuqid control over Syria had the effect of encouraging towns and cities in the country to seek independence, a movement usually led by the wealthy urban aristocracy, which, in large cities such as Damascus and Aleppo, did not claim formal independence from the Seljuq sultan, but was willing to cooperate with him through town heads (rais) who had at their disposal a local police force (akhdas). This kind of local self-government was formed in these cities in the X — XI centuries and allowed them to enjoy full autonomy.

A vestige of the Seljuk concept of family sovereignty was the custom of granting fiefdoms in border provinces to sons and relatives of the sultan, who received the title «malik» (king). Thus, Malik-Shah’s brother Tutush considered himself entitled to claim a special inheritance, and having conquered Central and Southern Syria with Damascus as his capital by order of the Sultan, he not only kept this area in his hands, but even appointed one of his cronies named Ar-tuk as the ruler of Jerusalem as his vassal. The powerless Malik Shah had no choice but to donate the captured lands to Tutush as a fiefdom. Later, after the death of Malik-Shah, Tutush even tried to seize power in the sultanate, but was defeated in 1095 in a battle with the army of Sultan Berkiyaruk (1094 -1105). After Tutush’s death in 1095, his possessions were divided between his sons, Ridwan, who ruled in Aleppo, and Dukak, ruler of Damascus. They continued to bear the titles of «Maliks» and, nominally remaining vassals of the Sultan of the Great Seljuks, under the weak successors of Malik Shah actually gained complete independence.

A special role in the fate of the provinces of the Seljuk Empire played a specific for the Seljuk state institution of atabeg. Initially Seljuk conquests were characterized by the migration of Oghuz Turks to the west, but when the conquests were completed, the sultan, being the ruler of a vast empire, felt the need to create a disciplined, personally devoted to him army, capable of keeping under control the Oghuz themselves. This army was composed of Mamluk slaves brought from Central Asia. Turks, who were pagans, were converted to Islam, trained in military science and, having been included in the court guard, were given their freedom. Moving up the military ladder, these former slaves could reach the positions of emirs, rulers in the provinces and high-ranking courtiers. The position of atabeg was one of the most tempting for the Mamluks. The word «atabeg» was of purely Turkic origin. It came from the combination of two words «ata» (father) and «beg» or «bek» (commander). Atabeg at first were assigned as tutors-uncles and mentors to young Seljuk princes-heirs. If an atabeg’s ward received a fiefdom or was appointed governor of a province, the atabeg became his regent and, in fact, gained power over his possessions.

Thus, after the death of Dukak in 1104, his former tutor (atabeg) Tugtegin continued to rule Damascus as the atabeg of his young son, and after the child’s death he ruled the city as an independent ruler until his death in 1128. After Tugtegin’s death, the power over Damascus passed into the hands of his son Buri, who founded a whole dynasty of rulers of the city — Burids (1104 -1146). Dukak’s brother Ridwan ruled in Aleppo and Hims, but when in 1097 he quarreled with his atabeg Janah al-Dawla, he seized Hims and became an independent ruler of this city.

Those Syrian cities that were under Fatimid rule were no less successful in their struggle for independence. Thus, in 1070, Tyre and Tripoli, ruled by Shiite qadis, became independent, and later the sheikhs of the Bedouin tribe Banu Ammar seized power over Tripoli. As a result, by the time the Crusades began, Syria was a kaleidoscope of small holdings of city rulers, emirs and Bedouin sheikhs in a state of continuous conflict with each other.

The cities of Iraq, according to the Arab medieval geographers, were in a better position at this time. Baghdad, Kufa, Basra and Wasit remained densely populated centers with developed crafts and trade. The internecine strife in the Seljukid power, which came in 1092 after the death of Malik Shah, allowed the Abbasid caliphs to restore their power in Iraq to some extent. When in 1157 another Seljuk sultan, Muhammad II (1153-1160), who ruled in western Iran, invaded Iraq and besieged Baghdad, the army loyal to the caliph was able to thwart all his attempts to take the city. After this event, the lost authority of the Abbasids grew so much that the rulers of the Syrian principalities fighting the crusaders began to turn for help to the Caliph al-Muqtafi (1136-1160). In Egypt, the fall of the Fatimid caliphate and the proclamation of Sultan Salah al-Din in Cairo in 1171, followed by the restoration of Sunni Islam, led to the resumption of the mention of the name of the Abbasid caliph al-Mustadi (1170-1180) during prayer.

The consolidation of Abbasid power in Baghdad had a favorable effect on the development of Arab culture in the capital and other cities of Iraq. In the late 11th and early 12th centuries, on the eve of the Mongol invasion, Baghdad was famous for its schools and libraries. Caliph al-Mustansir in 1232 founded in Baghdad the famous madrasa «al-Mustansariya», similar to «Nizamiyah» Nizam al-Mulk, by his order was built «Mosque of the Caliphs».

The weakening of the Seljukid state contributed to the political revival of some of the eastern provinces of the empire, particularly Khorezm. Located on the lower reaches of the Amu Darya, Khorezm was a rich agricultural area with an excellent source of water and artificial irrigation. Surrounded by steppes and semi-deserts that separated it from the outside world, Khorezm retained its independence despite repeated attempts of invasion by various conquerors. As early as 712, Khorezm became involved in the events of Islamic history when Kutayba ibn Muslim, the governor of Khorasan, invaded it. In 995, the local Mamunid family assumed the traditional Iranian title of Khorezmshahs. Khorezmshahs were by origin Turks, but, having perceived Islam, have got acquainted to Arab-Iranian culture. Formally Khorezm was under the rule of Samanids, though it lived an independent life. In 1017 Mahmud Ghaznevi annexed it, as well as many other areas of Samanids, to his empire, and in 1041 Khorezm, again formally, came under the rule of Seljukids.

The heyday of the Khorezmshahs’ state came in the last decades of the 12th and the beginning of the 13th century. In 1172 Khorezmshah Tekish (1172-1200), and after him Khorezmshah Muhammad (1200-1220) managed to significantly expand the limits of their possessions and achieved power over Western Iran, Maverannahr with the cities of Samarkand and Bukhara, Afghanistan and areas of Transcaucasia. Thus, the whole of Iran and Central Asia from India to Anatolia were in their hands.

In their attempts to expand the borders of the state to the west, the Khorezmshahs inevitably had to face the opposition of the Abbasids, who shortly before, under Caliph al-Muqtafi, had managed to withstand the Seljuk threat. Caliph al-Nasir (1180-1225), in turn, tried to expand the Caliphate’s possessions to the east and to include Khuzistan as well. Khorezmshah Muhammad refused to recognize al-Nasir as an imam-caliph and proclaimed one of the Alids, who came from Termez, as such. In 1217 he moved an army against al-Nasir, but, according to sources, winter cold forced him to return to Iran.

A few years later, in 1220, Genghis Khan’s Mongols invaded Maverannahr, and the reign of the last Khorezmshah Jalal al-Din was spent in vain attempts to save the power from the Mongol invasion. With his death in 1231, the state of Khorezmshahs came to an end.