This section of the paper is based on rather traditional oriental texts, which, however, we interpreted in the context of new source studies. Recent attempts (Yudin, De Weese) to use the text «Genghis-name», compiled in the XVI century by the Khorezmian connoisseur of legends Utemish-hajji, to cover this topic, do not seem successful to us because of the frank religious-apologetic character of this purely folklore text, which, however, is obvious from the recognition of the author of the work [Genghis-name, pp. 90-91; Bartold, vol. 8, pp. 164-165].

It has already been noted above that in the Golden Horde there was no single people; in the state of the descendants of Juchi there was also no single culture, religion, etc. In a number of sedentary areas that were part of the Golden Horde, such as Khorezm (lower Amu-Darya) and Volga Bulgaria, Islam was the dominant religion even before the Mongols, and there were Muslim schools and mosques. The population of the Crimean cities was under the influence of the Byzantine Church. The situation was different in the main — steppe, nomadic areas of the Golden Horde state, populated mainly by Kipchak Turks (Polovtsians) and Mongol aliens, their conquerors.

In the pre-Mongol period, the Kipchaks of the Great Steppe were almost unaffected by Islam and its culture. It is true that according to a legendary news, stated by the Arab historian of the XIII century Ibn al-Asir, in 1043 Islam was accepted by the nomadic population (about 10 thousand kibits in total), which lived in winter in the neighborhood of the Chu valley in Semirechye, and in summer — in the steppes near the country of the Volga Bulgars. Nevertheless, before the Mongol conquests the Kipchak steppe remained outside the limits of the Muslim world, and in the beginning of the 13th century the Muslim ruler of Central Asia Khorezm Shah Muhammad (ruled in 1200-1220) fought with non-Muslim Kipchaks on the Syr Darya and in the Turgai steppes (modern Central Kazakhstan).

The same situation was also in Western Desht-i Kipchak. The Kipchaks had Muslim preachers. Despite this, in the Caucasus Kipchaks in the XII century in alliance with Georgians took part in raids on Muslim lands, and Kipchaks, who roamed in the steppes near Southern Russia and the Crimean peninsula, were even under the influence of Christianity and part of them were Christians. Moreover, the propaganda of Christianity among the Kipchaks from Southern Russia and Western Europe continued in the Mongol period, which is evident from the Kipchak dictionary dating back to the end of the 13th century, where, according to V.V. Bartold, the texts of the Gospel and Catholic hymns (the so-called Codex Comanicus) are successfully translated into the Turkic language of the Kipchaks.

According to the sources, the dominant religion of the Kipchaks at that time was shamanism, expressed in the worship of the forces of nature, especially in the cult of Tengri (Heaven). It is remarkable that the ancient Mongols, who conquered the Kipchak steppe, were also pagans, and shamanism was also widespread among them. However, history has developed in such a way that the wide spread and strengthening of Islam among the nomads of Desht-i Kipchak, who had not been Muslims before, belong to the era of Mongol rule (XIII-XV centuries).

The state of the Golden Horde from the very beginning of its formation was exposed to the influence of Muslim religion and culture both from within — the Muslim population of the Bulgarian cities of the Volga and Kama regions, as well as the Muslims of Khorezm, and from outside — from nearby Bukhara and distant Egypt. The latter circumstance was facilitated by the military alliance concluded between the khans of the Golden Horde and the Mamluk rulers of Egypt and directed against the Persian Mongols, i.e. the Ilkhans, with whom the Djuchids were in hostile relations. This powerful influence of the Muslim world eventually led to the adoption of Islam as the official religion of the Golden Horde state by the Dzhuchid dynasty.

It has long been noticed that in the history of the introduction of Muslimism in the Golden Horde three stages are clearly distinguished: under the khan Berka (ruled in 1257-1266), under the khan Uzbek (ruled in 1313-1341) and under the emir Yedig (d. 1419), who in the early 15th century was actually the ruler of most of the Golden Horde.

According to Juvaini, the author of «History of the Conqueror of the World» (completed in 1260), Batu, the first ruler of the Golden Horde, did not favor any religion and adhered to the faith of his ancestors — the cult of the Eternal Blue Sky (Tengri). It is known that at that time many Genghisids were hostile to Islam, as Muslims led by Caliph Mustasim (killed in 1258 by Genghisid Hulagu when he took Baghdad) were the main external enemies of the Mongol Empire. Nevertheless, even during the lifetime of Batu (d. 1255) several of his younger brothers felt inclined to the religion of Islam and became Muslims. Among them was the tsarevich Berke, the future khan of the Golden Horde.

We do not have accurate and reliable information about when exactly Berke converted to Islam. From the story of the ambassador of the French king Louis IX to Mongolia Wilhelm de Rubruk, who visited the Golden Horde in 1253, it is clear that Berke was a Muslim until the specified year: «Berke, — writes his brother Wilhelm, — pretends to be a Saracen (i.e. Muslim) and does not allow to eat pig meat at his court».

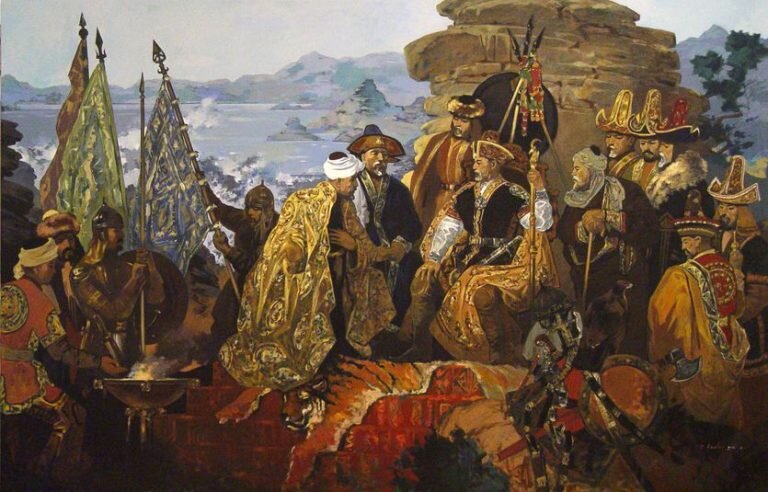

Tsarevich Berke, according to his contemporary Dzhuzdzhani, was taught the Koran in his youth in Khodjent (a city in Tajikistan, located on the left bank of the Syr-Darya River) by one of the scholars of this city. Berke visited Muslim scholars of theology in Bukhara and repeatedly talked with them. According to Arab authors, his adoption of Islam from the famous Sufi sheikh Sayf ad-Din Baharzi (d. 1261) also took place there, in Bukhara. According to al-Omari, this event took place at the time when tsarevich Berke was returning to the Volga region from Mongolia from the kurultai at which Munke (Mengu) was proclaimed the great khan, i.e. in 1251. It is said that after his accession to the throne in 1257 Berke visited Bukhara to honor the prominent ulema (scholar-theologians) of this city.

In the work of the Arab chronicler of the XIV century al-Mufaddal, whose information is taken from the works of earlier Arab authors, it is said about Berke that in 1263 he was 56 years old.

«His description: a liquid beard; a large face of yellow color; hair slicked back behind both ears; in one ear a gold ring with a valuable stone; he (Berka) wore a silk caftan; on his head a cap and a gold belt with expensive stones on green Bulgar leather; on both feet clogs of red shagreen leather. He was not girded with a sword, but on his girdle his black horns twisted, studded with gold» [SMIZO, 2005, p. 151].

According to Egyptian authors, obviously tendentiously exaggerated, not only Berke himself was a Muslim, but also his wives and some emirs with their warriors. Each of his wives and each of the emirs, who adopted the religion of Islam, as if had an imam (spiritual adviser) and a muazzin (a man who proclaimed the azan — the call to prayer); they carried their mosques, consisting of tents, with them. It is also said about Muslim schools, where children of dignitaries were taught to read the Koran; in the horde (nomadic stake) of Berke Khan there were constantly located scientists-theologians, with the participation of whom there were frequent evenings-disputations on the science of Sharia (rules, which should be guided by a faithful Muslim).

The adoption of Islam by Berke Khan, his wives and close associates, presented by Muslim authors as a victory of «Orthodoxy» in the Golden Horde, although it was for its time a fact of great political significance, but in reality it led neither to the mass Islamization of the main population of the state of the descendants of Djuchi, nor to a noticeable Islamization of state life and social life. It is known that in the Juchi Ulus and under the Muslim khan Berke (ruled in 1257-1266) pagan customs were observed with the same strictness as in Mongolia itself, including the custom most in conflict with the requirements of Islam: not to use river water for washing. When in 1263 Egyptian ambassadors arrived to the Volga region, to the headquarters of Berke Khan, they were warned in advance that they «should not eat snow, not wash their dresses in the horde, and if they happened to wash it, they should do it secretly». The fact that the khans of the Golden Horde who followed Berke (d. 1266) were pagans should also be considered as a fact of weak spread of Islam among the Dzhuchids and nomadic feudal nobility of Desht-i Kipchak; they, as al-Kalkashandi notes, «did not profess Islam until Uzbek Khan appeared among them».

Indeed, the reign of Uzbek-khan (1313-1341) was a golden period in the spread and strengthening of Islam in the Golden Horde: under him Islam was declared the official religion of the state of the descendants of Juchi and the Golden Horde culture received a certain Muslim imprint.

Arab (Egyptian) authors link the adoption of Islam by Uzbek to the circumstances of his accession to the throne. Uzbek’s predecessor on the throne, Tokta Khan (ruled in 1290-1312), according to Sheikh al-Birzali (d. 1338), was an idolater, loved «lamas and sorcerers and gave them great honor. Tokta Khan had a son; he was committed to Islam, liked to listen to the reading of the Koran, though he did not understand it, and assumed, when he became king of this country, to leave no other religion in his kingdom but the Muslim one. But he died while his father was still alive, leaving a son. When he died, his father, Tokta, appointed his grandson as his heir, but he was not able to rule, as after Tokta the kingdom was possessed by his brother’s son, Uzbek [SMIZO, 2005, p. 143-144].

According to the annals of al-Aini (d. 1451) and Ibn Khaldun’s «Book of Edifying Examples» (written in 1406), Prince Uzbek was elevated to the khanate by the senior emir of the country, Kutluk-Timur, and his supporters. And when the seizure of power was still being prepared, Kutluk-Timur as if took the word from the tsarevitch Uzbek that if he came to the throne, he would become a Muslim and would strictly adhere to the rules of Islam. Upon ascending the throne, Uzbek really killed a large number of shamans and Buddhist lamas, accepted Mohammedanism and «proclaimed the confession of Islam». Having become a Muslim, Uzbek-khan arranged a cathedral mosque in which he performed all five prayers, did not wear Mongolian caps anymore, began to wear a mace belt and said: «It is indecent for men to wear gold» [SMIZO, 2005, p. 380-381].

In an anonymous work called «Shajarat al-atrak» («Genealogy of Turks»), compiled in Persian language in the XV century, there is a story according to which Uzbek was converted to Islam and gave him the name of Sultan Muhammad Uzbek-khan by the Turkestan sheikh Sayyid-Ata; this event as if occurred in 720 AH (February 12, 1320 — January 2, 1321). It is noteworthy that on the coins of Uzbek-khan, minted from 721/1321-1322, his full name is written in the form «Sultan Muhammad Uzbek-khan», while coins minted at an earlier time usually contain the legend: «Supreme Sultan Uzbek».

Starting with Uzbek-khan, all the Golden Horde khans were Muslims and had a Muslim name in addition to their personal Turkic name. Thus, judging by the coins, Janibek Khan (ruled in 1342-1357) had a Muslim name Sultan Jalal ad-Din Mahmud, Berdibek Khan II (ruled in 1357-1359) — Sultan Muhammad, Toktamysh Khan (ruled in 1379-1395) — Sultan Nasir ad-Din, etc.

According to the Khorezmian historian Munis, during the reign of Uzbek, in connection with the final establishment of Islam in the Golden Horde, the Turkic word bek (biy) was displaced by the Mongolian noyon.

In connection with the adoption of Islam by the Dzhuchid dynasty, the fact that in the second quarter of the 14th century Islam was declared an official religion in the Chagataid state deserves to be emphasized. Thus, already in the XIV century Islam became the state religion in the entire area conquered by the Mongols in the west, from Southern Russia to the borders of Mongolia proper and China.

The ruling elite of the Golden Horde supported not only the Mohammedan religion. In many cities of the Crimea, the Volga region, etc., mosques neighbored churches and monasteries. In particular, in Sarai, the capital of the state under Uzbek-khan, according to the great Arab traveler Ibn Battuta, who visited it in 1333-1334, there were «13 mosques for the cathedral service; one of them was Shafi’i. In addition, an extremely large number of other mosques. In it (Sarai) live different peoples, such as: Mongols are the real inhabitants of the country and its rulers; some of them are Muslims; Ases, who are Muslims; Kipchaks, Circassians, Russians and Byzantines, who are Christians. Each nation lives in its own section separately» [SMIZO, vol. 1, p. 306].

Another source of the XIV century says that the population of the Golden Horde is numerous and diverse in composition, that along with Christians among them «there are Muslims and infidels». To all appearances, in the XIII-XIV centuries the rulers of the Golden Horde showed complete tolerance in matters of faith of their subjects.

About the nature of religious tolerance of the Djuchids it is wonderfully aptly stated in a letter of a brother of the Order of Minorites, Johanka Vengra, who visited the Golden Horde in 1320. «For the Tatars, — he wrote to the head of the Order, Baron Michael, — by military might subjugated to themselves different tribes of Christian peoples, but allow them to still keep their law and faith, not caring or little caring about who holds what faith — so that in worldly service, in payment of taxes and fees and in military campaigns they (subjects) did for their masters what they are obliged to do according to the issued law». [Anninsky, p. 90-91].

Summing up the Islamization of the Juchiye Ulus in the XIV century, it should be said that the spread of Mohammedanism was most successful among the power elite and urban population of the Golden Horde state. The nomadic steppe — Desht-i Kipchak — in the XIV century as a whole was very superficially affected by Muslimism, and the inhabitants of the steppe in their masses were still in the power of the old shamanistic beliefs, as evidenced by the preservation of ancient pagan burial rites.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the emir Yedige (Idiki, Idiku) attempted to introduce Islam by force among the nomadic population of the Golden Horde.

Yedige is a legendary personality in general. «Long stories are reported about him,» writes al-Zahabi (d. 1449), an unknown continuator of the Chronicle of Islam. — I met a man who had seen him (Yedige), knew his deeds and spent several years with him. He told me amazing and extraordinary things about him concerning his courage, knowledge, courtesy, ability to rule and his greatness» [SMIZO, vol. 1]. [SMIZO, vol. 1, pp. 553-554]. And here is what reports about Yedig Ibn Arabshah (d. 1450), who lived for many years in Maverannahr and at the turn of the 20-30s of the XV century. who visited the Golden Horde: «He was very swarthy in face, of medium height, dense build, brave, fearsome to look at, of high intelligence, generous, with a pleasant smile, apt shrewdness and cleverness, a lover of scholars and worthy people, approached pious and fakirs, talked (joked) with them in the most affectionate expressions and humorous innuendos, fasted and rose at night to pray, held fast to the hollow of the Shari’ah, making the Qur’an and Sunnah and the sayings of the sages as mediators between himself and Allah Most High. He had about 20 sons, each of whom was a lordly king, who had his own special inheritance, troops and supporters. He ruled over all the affairs of Desht for about 20 years. The days of his [reign] were a bright spot on the forehead of the centuries, and the nights of his rule — a bright stripe on the face of time.» [SMIZO, vol. 1, p. 473-474].

Emir Yedige came from the Turkicized Mongolian tribe Mangyt and became a legendary hero even during the reign of the Golden Horde Khan Toktamysh (1379-1395). However, his actual entry into power took place only after the complete defeat of Toktamysh from Emir Timur in 1395. Events unfolded in such a way that from that time until his death in 1419 he was the full ruler of most of the Golden Horde. But Yedige, not being Genghisid (a male descendant of Genghis Khan), did not take the title of khan, but carried only the title of «emir» (in the meaning of Mongolian noyon and Turkic bek or biy; These titles in the state of the descendants of Djuchi and in the Chagatai ulus were called representatives of the military nomadic aristocracy) and enthroned false khans from the descendants of Genghis Khan, remaining under them amir al-umar («emir of emirs»).

Yedige in a short time put in order the state, upset by two (1391 and 1395) devastating invasions of Emir Timur and, according to the author of «Muntahab at-tawarikh-i Mu’ini», started in the Ulus Juchi «fine rules and great laws». In particular, he, as the Arab author Makrizi (d. 1441) notes, forbade «Tatars» to sell their children into captivity, as a consequence of which their importation to Syria and Egypt decreased considerably. On another occasion, the all-powerful «emir of emirs» turned his high gaze to the state of the religion of Islam in the state of the descendants of Djuchi. Here is what is reported in this connection by Josaphat Barbaro, an Italian merchant who lived many years (1436-1452) at Tana, a Venetian colony at the mouth of the Don:

«The Mohammedan faith became common among the Tartars already about one hundred and ten years ago. It is true that only a few of them were formerly Mohammedans, but in general every one was free to adhere to the faith he liked. Hence there were some who worshipped wooden or cloth statues and carried them on their carts. The compulsion to adopt the Mohammedan faith dates back to the time of Yedigey, the commander of the Tatar khan, whose name was Sidakhamet-khan» [Barbaro, p. 140].

The specific measures of coercion are not reported.

It is noteworthy that at the same time with Yedige diligently cared about the spread of Islam in his possessions Mogolistan Khan Chagataid Muhammad (ruled in 1408-1416). According to Mirza Haidar, the author of the official history of the Mughal khans, according to the order of this sovereign, all Mughals (i.e. the nomadic population of the country) had to wear the turban; those who disobeyed had horseshoe nails hammered into their heads. By such cruel measures Muhammad Khan, according to the writer of «Tarikh-i Rashidi», achieved that the majority of nomadic tribes and clans of Mogolistan became Muslims.

Yedige’s plan to forcibly convert all the nomads of Desht-i Kipchak to Muslimity may have strengthened the religious principle to some extent. However, these forceful methods of solving religious problems did not lead to the complete victory of Islam over the entire Kipchak steppe. In any case, according to the testimony of I. Schiltberger and Ibn Arabshah, who visited the Golden Horde in the 20-30s of the XV century, as well as according to the accounts of a number of other authors, in the XV century in Desht-i Kipchak there were many pagans, i.e. many adhered to shamanism. This situation persisted in part of Desht-i Kipchak in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In this regard, it should be emphasized that the Kazakhs, whose ethnic core was composed of clans and tribes of the Kipchak association, in the 16th century were considered Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi persuasion. But along with this, some «customs of paganism» were widespread among them, which, according to Ibn Ruzbihan, a participant of Muhammad Sheibani-khan’s campaign against the Kazakhs in the winter of 1509, were expressed in three ways. First, the Kazakhs had images of idols, which they worshipped earthly. Secondly, the Kazakhs turned captured Muslims into slaves without making any distinction between them and infidel slaves. Thirdly, when spring comes and koumiss appears, Kazakhs, before pouring koumiss into a vessel and drinking it, «turn their face to the Sun and splash out a small amount of drink from the vessel towards the East, and then make an earthly bow to the Sun. Probably, this is a manifestation of gratitude to the Sun for the fact that it grows herbs, which the horse feeds on, and koumiss appears» [Ibn Ruzbikhan, p. 105-108].

A new stage in the spread and strengthening of Islam among the nomads of the Kipchak steppe is associated with the activities of the Russian government.

When in the second half of the 16th century Russia incorporated the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan and Siberia (Tobolsk), the Russians got acquainted with the Tatars of the Volga region and the Bashkirs as peoples who had converted to Islam. In Russia, a prejudiced view was formed according to which all the population of the former Juchiye Ulus were faithful Mohammedans, and Islam was the only source of their worldview, their state system and social life. It is noteworthy that as early as in the first half of the 18th century the Russian government discussed the past, present and future of the Turkic-speaking nomadic peoples of the Great Steppe, in particular the Kazakhs, from this erroneous point of view. That is why the ambassador of Empress Anna Ioannovna A. I. Tevkelev, sent in 1731 to the Kazakh steppes, to the khan Abu-l-Khair, to accept the Kazakhs of the Kishi zhuz (Younger Horde) into Russian subjection, had a strict instruction. According to this instruction, drawn up within the walls of the Collegium of Foreign Affairs, A. I. Tevkelev had to try, «as the most important thing, to ensure that in loyalty to her Majesty. Abu-l-Khair-Khan with all the other khans and chiefs, and with all the other Kirghiz-Kaisaks swore an oath on their faith on alkoran (my emphasis. — T. S.), and signed it with their own hands, and gave it to him, Tefkelev».

Meanwhile, in the steppes of Kazakhstan and in the first half of the XVIII century Islam was the religion of the people in name only. As far as we know, among the bulk of Kazakhs and at that time the requirements of Islam (i.e., the five pillars of Islam: 1). Five basics of Islam: 1) confession of one God, Allah, and his messenger, Muhammad; 2) fivefold prayer; 3) fasting in the month of Ramadan; 4) payment of tax in favor of the poor; 5) pilgrimage to Mecca, to the Kaaba — the main shrine of all Muslims) were little known, religious rites were not performed by all, but the vestiges of pre-Muslim beliefs were very strong. In this connection the following fact is interesting. The famous Kazakh khan Abu-l-Khair died in the summer of 1748 and was buried according to the Muslim rite. However, according to the «Daily Notes» of Captain N. P. Rychkov (d. 1784), Abu-l-Khair Khan was put in the grave «in ordinary clothes and with some military equipment, such as: a saber, a spear and arrows». From the words of N. P. Rychkov it is clear that, despite the observance of the basic ritual of Muslim funeral rites, the elements of the ancient pre-Muslim funeral customs of nomads of Central Asia were also preserved: funerals in ceremonial dress and with weapons. The Muslim rite required burial in a shroud and without any household items.

The sergeant of the tsarist army Philip Efremov, who in 1774 was captured by the Kazakhs, then lived for a long time in Maverannahr and through India and England returned to Russia in 1782, wrote about the religion of the Kazakhs as follows: «The Kirghiz are of the Mohammedan religion, but they seem to have a very weak notion of it, so that it seems as if they had no faith at all». [Travels in the East, p. 194].

In short, despite the official transition to Mohammedanism, Islam had nominal importance in the life of Kazakh nomads and had almost no influence on the state structure and social life of the people. Paradoxically, the final victory of Islam in the steppes of Kazakhstan (i.e. in the eastern part of the former Desht-i Kipchak) took place after the Kazakhs accepted the Russian protectorate and with the energetic assistance of the Russians — followers of Christianity.

The attitude of the Russian government towards Islam varied in different historical periods. Initially, the Russian government, when conquering new lands on the Asian mainland, did not patronize Islam, but did not resort to direct violence against the conscience of its Asian Muslim subjects and did not lead them to baptism by fear. It is true that the government then began to persecute Islam. Especially fierce persecutions against Islam were in the Russian Empire in the 40s of the XVIII century, when a nominal decree ordered to spread Christianity among Muslims, to exempt the newly baptized from taxes and recruitment, imposing both on the unbaptized; when the Senate decree destroyed mosques in the basin of the Volga and Kama rivers. But since religious persecutions caused uprisings of «eastern foreigners», and the planting of Christianity among them gave negligible results, the government in the second half of the XVIII century changed its attitude to Islam. Now the Russian government consciously began to promote the spread of Islam and strengthen its position in its Asian possessions. By a special decree, the tsarist government ordered the construction of mosques; in particular, in 1755, it was permitted to establish near Orenburg the so-called Seitovsky settlement with a magnificent mosque, which, together with its religious colony in Sterlibash, in the Ufa province, became a new center of Muslim science on the border with the Kazakh steppe. From here, with the knowledge of the Russian authorities, Muslim preachers were sent to the Kazakh steppes to plant Islam and mullahs to organize Muslim religious schools and educate children. The fact that in the 80s of the XVIII century, according to the materials of M. Vyatkin and I. Erofeeva, a certain Khoja Abu-l-Jalil, who had the honorable title of «Pir (spiritual adviser. — T. S.) of the whole Kyrgyz-Kaisak jurt», i.e. a kind of steppe sheikh ul-Islam, officially acted in the Kazakh steppes.

Thus, henceforth Muslim culture and Islam spread in Kazakhstan not only from the south, as it was originally, but also from the north. This circumstance eventually led to the fact that the former Kipchak steppe has now completely and finally become a Muslim country (dar al-islam).