For the Ottoman sultans, Rome did not end in 1453 with the conquest of Constantinople, but passed into their possession

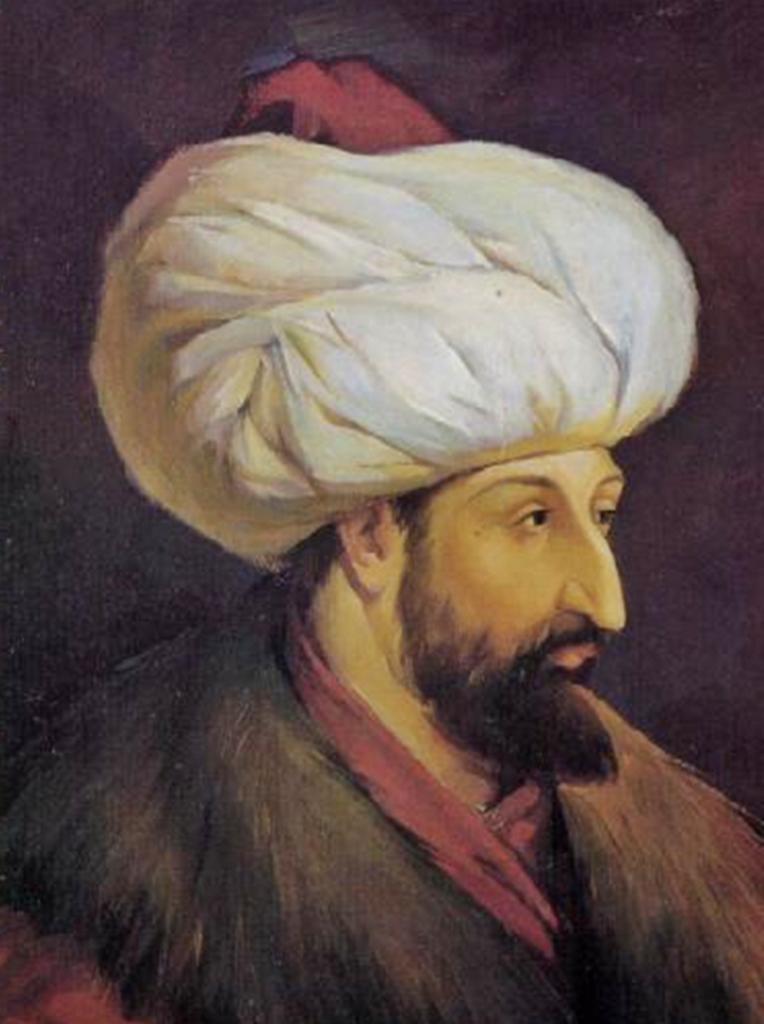

On May 29, 1453, an Ottoman army led by the young Sultan Mehmed Fatih stormed Istanbul, ending the Christian Paleologos Empire. A few years later in 1461 the same sultan took Trabzon, the capital of the Trebizond Empire of the Comnenian dynasty. Thus ended the long history of the Eastern Roman Empire, which we know today as Byzantium.

The capture of Istanbul by the Ottomans caused shock in the wider Christian world and increased apocalyptic sentiment in anticipation of the end of the world. But at the same time it also set off a wave of debate about who was now the true Rome or its successor. For the Western Christian world such «true» Rome was the Holy Roman Empire, where shortly before the capture of Istanbul (in 1437) reigned the Habsburg dynasty, which would rule until the end of the empire in 1806. Meanwhile, in Russia, the famous theory of the «Third Rome» became popular, for the role of which Moscow, a state with Orthodox rulers and kinship with the Paleologos dynasty, was projected.

But for the Ottomans, who raised their banner over the lands of Byzantium, the question of who was the true heir to Rome, had a clear answer. They were its only heirs.

This was clearly expressed in the adoption by Sultan Mehmed Fatih of the title Kaiser-i Rum — «Caesar of Rome», which had previously been used in Turkish sources as a designation of the Byzantine emperor. Since then, the Ottoman sultans have worn many titles — hakan or khan (the Turkic equivalent of «emperor»), padishah (essentially also emperor, only in Farsi), caliph (a claim to spiritual leadership in the Muslim world) and many others, but invariably among them was the title of «Caesar of Rome». The Ottomans took their Roman emperorship so seriously that they refused for a long time to recognize the Habsburgs as Holy Roman Emperors and persistently referred to them as «kings» in all diplomatic documents until the 17th century.

The idea that the Ottoman Turks, who created a Muslim empire, could somehow be the heirs of Rome — the cradle of European civilization — was outrageous and even blasphemous for European Christians then and remains largely so now. It should be noted, however, that this idea is equally unfamiliar and alien to most modern Turks, who are accustomed to considering Byzantium only an enemy of their ancestors.

Discussions about Rome, Roman identity and Roman heritage are unlikely to come to an end, and we will probably never see any consensus on this issue. Still, we must remember that the Rome of the Paleologoi and Comneni differed from the Rome of Caesar and Sulla as radically as the Rome of the Ottomans differed from the Rome of Constantine. Nevertheless, this legacy is recognized. From the Ottoman point of view, their claim to Roman heritage was no worse.

What is the basis of the idea of Ottoman Rome?

Land

First of all on the idea of the land itself — Rum (Rome, Romania). The Turkic-Muslim beys who conquered Byzantine territories in the late eleventh century, such as the Danishmendids, referred to themselves on their coins as «Great Kings of Romania and Anatolia.» The Anatolian Seljukids, whose principalities were located in the region of Konya and southern Cappadocia, called their state Rum, at least unofficially, and themselves the Seljuks of Rum, thus to some extent considering themselves heirs of the Byzantine territory in South-Central Anatolia. Rum at the same time continued to refer both to the territory and people under the political rule of the Byzantine emperor in Istanbul, and to Greek Orthodox Christians living under the political rule of the Muslim Turks.

The famous Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta, who visited Anatolia in the 1330s, describes the region as «a Turkic land known as the lands of Rum.»

Ottoman expansion in the fourteenth century eventually made them masters of former Byzantine territories in both Anatolia and the Balkans. Since the territories of the late Byzantine Empire were mostly in Europe, these areas became for the Ottomans Rum-eli or Rumelia, a land characterized by a predominantly Orthodox Christian population.

The Ottoman ruler Bayezid I (reigned 1389-1402) adopted the title Sultan-i Rum (Sultan of Rum), probably to express his superiority over the other Turkic emirates in Anatolia and to emphasize his right to be the true successor to the Seljuks of Rum. Other Ottoman rulers, including Mehmed I (1413-1421) and Mehmed II Fatih (444-1446, 1451-1481) adopted the title Sultan-i Rum even before the capture of Istanbul, considering themselves heirs of both Byzantium and the Seljuk Sultan of Rum.

In other words, Muslim Turks physically lived and ruled in a land that was known long ago as Rum. Moreover, in the geography of Turkey, the concept of Rum persists even today. First of all in the name of Rumelia (the European part of Turkey), but also in the name of, for example, the city of Erzurum («the land of Rum»).

City

Closely related to the concept of land, i.e. cultural geography, is also the concept of Rome as a City. Both in Byzantium itself, and in Turkic-Muslim sources, Rome (Rum) was often meant primarily as Istanbul, the capital of the empire, and its immediate surroundings. The capture of Istanbul and the transfer of the capital of the Ottoman state there symbolized the transition of power over Rome from Christian kings to Muslim sultans.

For Ottoman Muslim intellectuals of the time, the Islamization and Turkification of Rome was similar to the Islamization of Aya Sofia, a former Byzantine temple. An Ottoman author writing in 1480 argued, this temple was to be built on the site of a pagan temple and symbolize the victory of Christianity over paganism. Stones from destroyed pagan temples from various lands were used as its foundation. Ottoman texts also contain the news that the dome of Aya Sofia collapsed on the night of the birth of the Prophet Muhammad.

In a similar way, the Ottomans treated the entire Roman heritage of the city. They did not deny it, but incorporated it into their new Ottoman civilization.

A huge role in this process of incorporating the Byzantine heritage into the Ottoman one was played by people who belonged to both civilizations.

People

To understand how enthusiastically the Ottomans incorporated Byzantine and Balkan nobles into the highest echelons of their own administration, we can look at the biographies of the men who became grand viziers after the capture of Istanbul.

When the Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI Paleologos fell on May 29, 1453, he left no heirs. Both of his marriages were childless. According to the famous Ottomanist historian Professor Heath Lowry, if the capture of Istanbul had not then become the end of Byzantium, it is likely that Constantine’s heir would have been one of the three sons of his late elder brother. All three failed heirs were eventually accepted into the service of Sultan Mehmed Fatih.

We meet one of the nephews 17 years later in 1470 already under the name Mesih Pasha. He was an admiral of the Ottoman fleet and sanjak bey (governor) of Chanakkale (Gallipoli). And in 1481 Sultan Bayezid II appointed him grand vizier. He stayed in this post for 2 years, then became vizier again in 1499 and died in this post.

His brother Has Murad Pasha became beylerbey (governor) of Rumelia in 1472. Four years later he led the Ottoman army in a war against Uzun-Hasan, ruler of the Ak-Koyunlu confederation, was ambushed and killed.

The career of the third brother is harder to trace, but there is speculation that it was none other than Gedik Ahmed Pasha, who became vizier in 1473. Some Western sources claim that Gedik was of Paleologian descent. Other sources, however, say that he was descended from the petty Serbian aristocracy.

Whatever the case, two men who might well have been crowned one day as Byzantine emperors instead found themselves at the pinnacle of power in the very state that ended Byzantium.

The Paleologos brothers were not unique in this endeavor. In the half-century between the conquest of Istanbul and the conquest of Syria and Egypt in 1516-1517, several other children of Byzantine and Balkan aristocracy became grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire. It is important to emphasize that we are talking specifically about Islamized Byzantine-Balkan free aristocrats, not peasant descendants who were conscripted under the devshirma (a system of personal dependence on the sultan) as janissaries. Of the sixty-five years after the capture of Istanbul and before the war with the Mamluks, at least thirty-five years the viziers were just such free aristocrats.

According to Professor Lowry, «the apparent ease with which Byzantine and Balkan aristocrats embraced the religion of their new rulers suggests that the late stigma of ‘Turkification’ was treated differently in the fifteenth-century Ottoman world.»

It is fair to mention that this process was not one-way until the final fall of Byzantium. This mutual influence brings us to the following thesis.

Culture

Centuries of interaction between Muslim Turks and Byzantines had a significant impact on both. The popular view that Istanbul was simply one day invaded by foreign hordes from the East is at least a very strong simplification.

The Byzantines were in close contact with the Turkic world even before the Seljuks came — Turks served in the army, traded with Turks, Turks accepted Christianity, and so on. After the Turks began to settle in Anatolia, establishing their own states, this communication intensified. After all, we know examples of not only allied relations between Byzantines and Turks, but even dynastic marriages. The Trabzon Komnins were especially distinguished in this sense, who often married their daughters to Turkic rulers — the descendant of the Komnins was, for example, the founder of the Iranian Safavid dynasty, Shah Ismail I, great-grandson of the Trabzon emperor John IV.

Emperors of Istanbul were not so often related to Muslims, but the second ruler of the House of Osman, Orhan Bey, married the daughter of Emperor John IV Cantacuzin, and at the same time helped his father-in-law in the dynastic war.

Women, as a rule, remained Christian and moved to husbands with extensive Greek courts. As a result, a special mixed Greek-Turkic world emerged at the courts of sultans and beys. As MSU professor Rustam Shukurov, author of a magnificent book on the Turks in the Byzantine world (The Byzantine Turks, 1204-1461), writes:

«Greek women were valued as the most prestigious marriage partners among all strata of Muslim society. It was the Greek women who led their Muslim husbands and masters to the refined Byzantine way of life and the world of Byzantine luxury, introducing, among other things, new cuisines and ways of arranging the household…..

Greek blood flowed in the veins of the Seljuk sultans, whose mothers and grandmothers were Greek women, often of noble descent. These blood ties between the sultans and the Greeks are extremely important in understanding the cultural environment at the Seljuk court. The influence of several generations of Greek women in the harem cannot be underestimated. Their presence inevitably influenced the cultural experience of Seljuk princes and princesses, including even those who were born to Muslim wives and concubines but lived in the harem with its Greek members. This influence was inevitable because Christian women continued to practice Christianity, praying in harem churches and surrounded by Christian ministers, servants and priests. In other words, Christian women had all the prerequisites necessary to reproduce Christian culture-though mostly only within their little harem, the intimate world of women and children. Significantly, Christianity and Byzantine culture (language and customs) existed in the harem not as a remnant of these women’s former lives, but as a living system that helped shape the future.»

As a result, a two-way process was taking place. On the one hand, there was a «latent Turkization» (as Shukurov put it) of Greek-Byzantine society, even that which was not under Muslim rule. Greeks adopted the language, clothing, cuisine and customs of Muslim Turks, to the point that late Byzantium had its own «Janissaries» — the name given to the palace guards.

On the other hand, Turkic rulers in general, and the Ottomans in particular, were deeply influenced by the Greek Byzantines. Today there is debate as to how much of a phenomenon or institution of Ottoman life is Byzantine, Turkic, or Arab-Persian-Islamic. But one of the most visible Byzantine influences on the Ottomans remains the ancient architecture we can see in Istanbul, Edirne, Bursa, and even in places like Crimea or Syria (where the style is known as «Rumian»).

The people

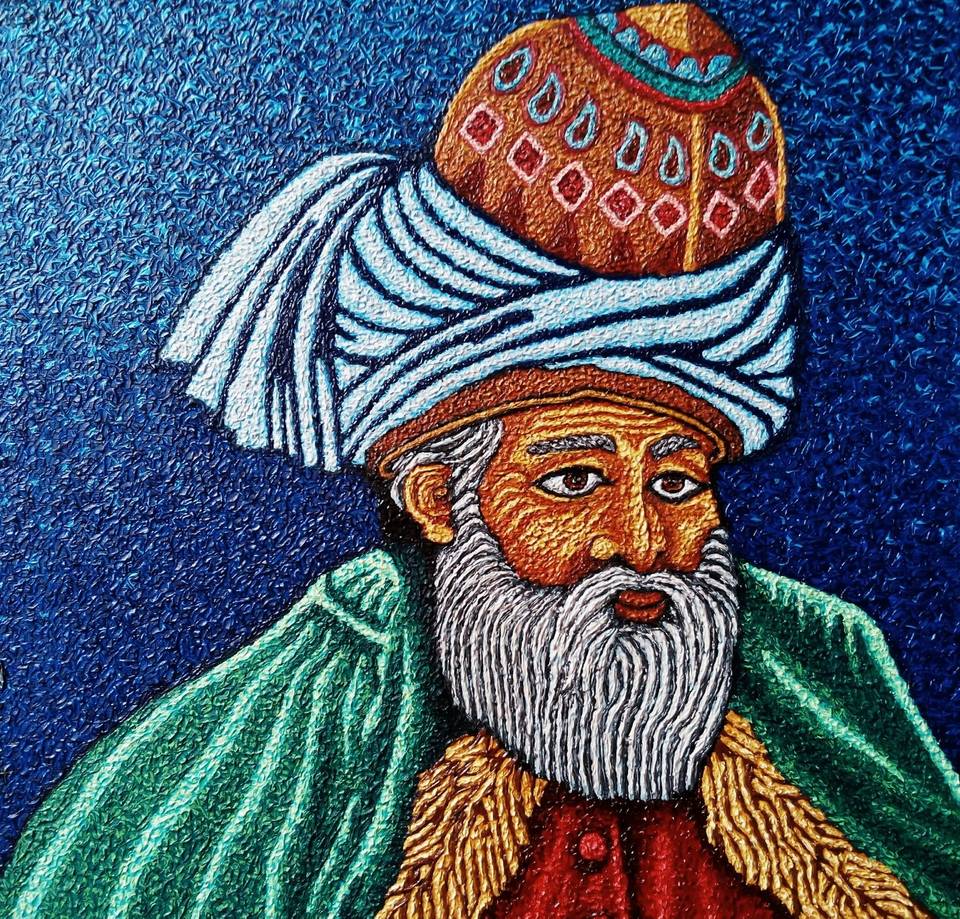

All these factors led to the formation of the Muslim Rumiyan identity, the people of Rum, in the 13th and 14th centuries. Mevlana Jelaleddin Rumi (d. 1273) is the most famous example, and today millions of modern readers refer to him simply as «Rumi.» Although there is no evidence that he called himself this, he was already widely known as Mawlana Rumi (Lord of Rum) in the early 14th century. The nickname «Rumi» appears in the 13th century and is used by many scholars, poets and Sufis. It is also used to refer to the collective identity of a certain segment of society: those who spoke Turkish (preferably in refined Turkish, but not necessarily as their mother tongue) and lived in cities. Ottoman Muslims were also called Rum or Rumiyans by Muslims in the East (e.g., in India) and by their Christian opponents (e.g., the Portuguese).

This identity was never a state identity, for the state itself called itself Ottoman, not Rumiyan, although the sultan did call himself «Caesar of Rum.» According to Turkish historian Cemal Kafadar, the Rumian identity was created and maintained by «civil society.» Ultimately, it was this failure to anchor it in state ideology that led to the fact that in modern times almost exclusively the Greek Orthodox Christians of Turkey (but not the Greeks of independent Greece itself) were already associated with Rum.

Rome-Rum

The appropriation of «Romanity» by Turkic-speaking Muslims in Seljuk and Ottoman times is not comparable to, say, the claims of the British elite of the nineteenth century and its attachment to the legacy of Rome, since it was not the (imaginary) image of Rome that was adopted, but the land where the Rumiyans lived and some cultural traditions and mores that were continued in Ottoman times. And this was done most often not to get some political «blessing», as in the case of American neocons or Russian imperials. For the Ottoman sultans, proclaiming themselves Rome was for the most part a simple statement of fact.

In any case, as Heath Lowry rightly observes, it is time for a reassessment of the idea that a change of religion on the part of the ruling elite necessarily equates to a serious «fault line.» Just as we recognize the continuity of the Roman Empire in the east in the person of Byzantium, despite the religious upheavals associated with the replacement of pagan beliefs with Christianity, we might recognize the continuity between the Byzantine Empire and its successor, the Ottoman Empire.