The Khitan (Karakitai) state in Central Asia — Western Liao was a unique phenomenon in the history of the region. Neither before nor after the Khitans, the ancient land of Maveranakhra was never again ruled by the laws of the Chinese state (East Turkestan is historically not included in Central Asia), as it was in a fairly short period of history from 1125 to 1211.

The borders of the Karakitai State Western Liao

In the Karakitai Khanate, Chinese was used in office work and the Confucian model of government was used. The Khitan also had, as later among the Mongols, the term paiza, to denote official powers.

The military-administrative management used a purely Chinese model — the absence of specific power, when military forces were divided between the upper aristocracy of nomads who ruled in different parts of the state. The Khitan gurkhan did not give anyone more than 100 horsemen, and even those only for protection and as spies.

At the same time, a large territory inhabited by various tribes and faiths was taken into account. Each region of the khanate was granted autonomy and it was ruled by its own dynasty — usually from the Karakhanids, in Uighur from local princes.

Submission to the Karakitai was expressed only in the payment of tribute, as well as in the presence of a representative of the Khitan gurkhan at the court of the local ruler. But often the representative came only to receive tribute, and then the local rulers were already able to take tribute themselves to the central headquarters of the gurkhan in Balasagun. This administrative system was then adopted by the Mongol Empire.

According to the Chinese model, the Khitan had a system of household taxes: one gold dinar was levied from each yard. It was a very easy taxation system, and even the poor could pay for it with the help of a mahalla (phratry at the place of residence). The system took root in Central Asia and was used in the Central Asian khanates of the 19th century.

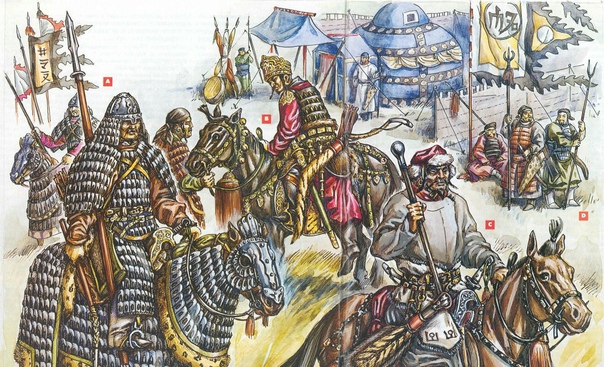

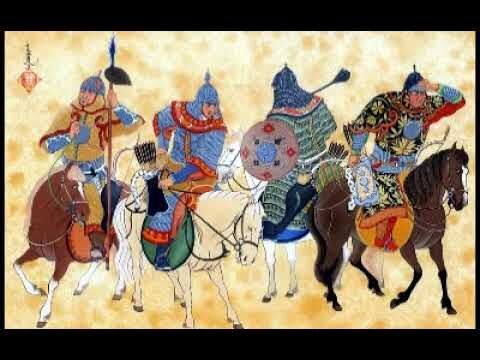

Khitan Warriors

Confessionally, the Karakitai state tolerated all religious beliefs — pagans-Tengrians, Muslims, Nestorian Christians, and Buddhists performed their rituals here.

The Karakitai themselves did not live in cities, and wandered in the river valleys of Talas and Chu. Despite the existence of a tribal system, women were very important and had broad rights among the Kara-Chinese, who were actually equal in rights with men — a very interesting moment for the peoples of Central Asia, where a woman was separated from public life.

However, this situation of women also led to the usurpation of power at the regional level on their part and their lovers. So, there is a legend about how one such tribal ruler, at the request of the people, killed a lover in front of her population, who began to behave unnecessarily brazenly — V. Bartold, lecture 7 on the history of the Turkic peoples of Central Asia

Thus, the Khitan state was organized in full accordance with local customs and conditions, which, coupled with a strong army, which for the first time among the nomads began to be paid salaries, helped to avoid tribal troubles and constant internecine strife of the nomadic aristocracy.

The Karakitai state was defeated by the Naiman Christians in the early 13th century, and then finally defeated by the Mongols during their invasion of Central Asia.

But the Chinese state of Karakitai remains one of the most interesting moments in Central Asian history, which shows how the nomadic people were able to successfully combine Chinese culture, the Confucian model of the state with a typically nomadic culture. No one else has ever managed such a successful combination.